America’s ‘Diner Man’ Is Donating His Life’s Work to the Henry Ford Museum

Half a century of menus, matchboxes, and postcards finds a home.

Nearly 50 years ago, when Richard Gutman was studying at Cornell University, a British designer asked him about diners. Why do Americans love them? Why do they all serve the same thing? And why do they all look like that? In an effort that earned him his nickname, “Diner Man,” Gutman spent the next 48 years answering those very questions, amassing the country’s largest collection of diner artifacts along the way. Recently, he donated his collection to Michigan’s Henry Ford Museum—a move that will make it a go-to destination for diner devotees.

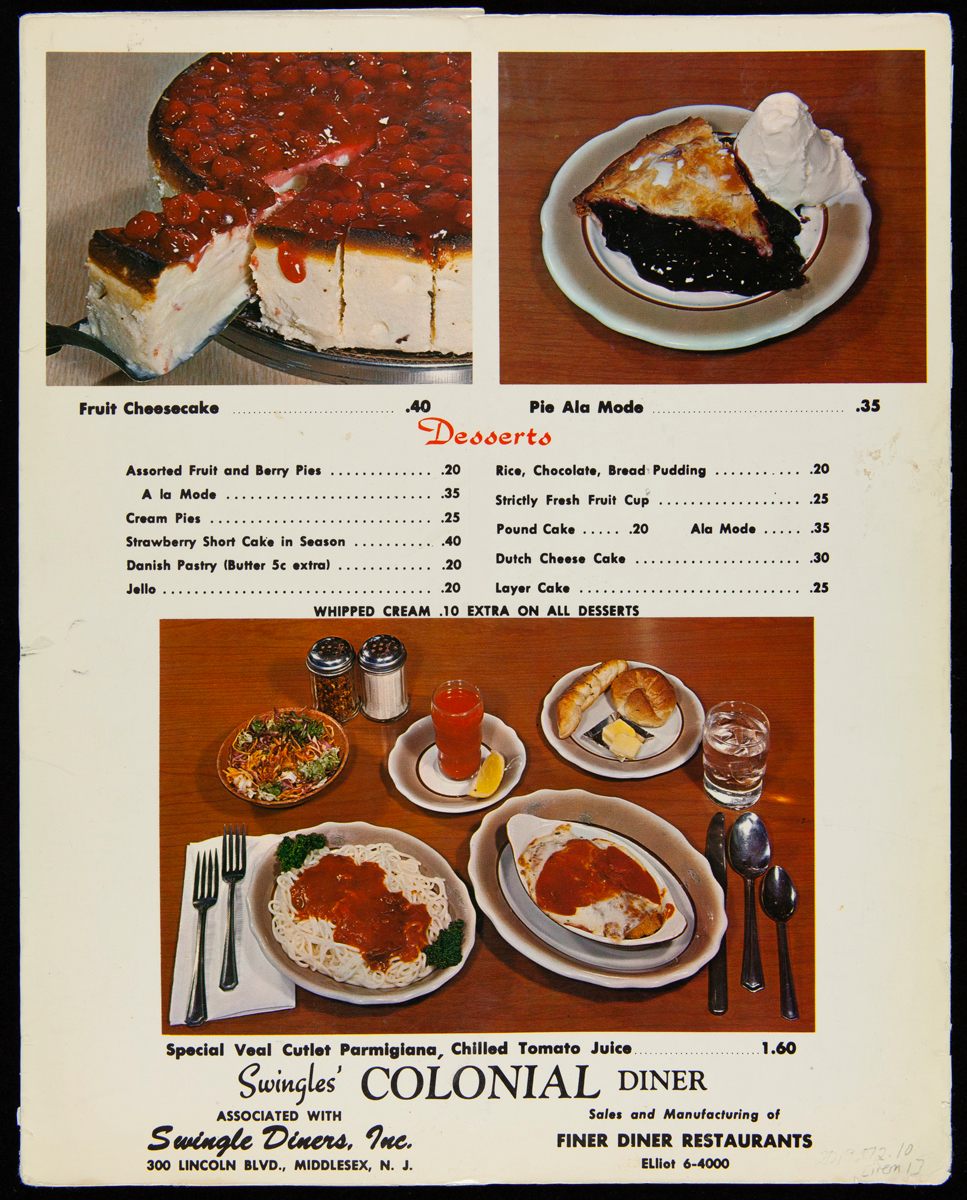

The 2,800-pound collection, Gutman estimates, consists of a 7,000-image library and 92 boxes of diner paraphernalia—menus, matchboxes, toothpicks, postcards, and more. When it wasn’t on temporary display in various museums, the contents stayed with him in his family’s home. “It’s part of the environment in which my wife and my daughter and I grew up,” says Gutman.

Coming of age in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Gutman was never far from diners. With four in walking distance of his house, they became a focal point of his early social life. “We got steak sandwiches—Allentown style, not Philadelphia,” he says, referring to the signature tomato sauce that defines the former. He took the landscape of humble eateries for granted until the British designer’s inquiry. “The story of the diner hadn’t been written—nobody cared about it,” says Gutman. “I was fortunate to stumble upon an unexplored slice of life, and I’m still talking about it.”

Gutman made diner architecture the focus of his undergraduate thesis, starting his academic foray by photographing the Fenway Flyer Diner in Boston, Massachusetts. “I didn’t roll the film all the way in before I closed the camera, so there’s a light leak on that first image—a telltale sign this was number one,” says Gutman. He says his studies aligned with a nascent interest in the 1970s in everyday, material culture. A slideshow he delivered in 1972 at New York City’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts called “Adam and Eve on a Raft” (“that’s two poached eggs on toast—diner slang,” he says) was written up by the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” section, launching a nationwide tour of presentations on diner architecture and food. “It was the right time; I was very lucky,” says Gutman.

The years that followed saw Gutman pioneer the study of American diners. Eating in countless diners while on the road, he diligently logged each one’s unique history and design, gathering materials while taking photographs long before social media had normalized the practice. “Sometimes there’d be a guy who’d come out with a big butcher knife asking if you were from the Board of Health,” he says. “Times have changed.”

While touring the country and accumulating a trove of artifacts, Gutman pieced together the story of roadside American diners as unique to a country so inextricably tied to the automobile—diners were the culinary appendage of a vehicular nation. To date, he’s restored dozens of diners, published four books, and presented lectures and slideshows at the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Geographic Society, and the United Nations.

Gutman says the greatest achievement of his career, however, is securing a place for the repository of his decades-long obsession in the Henry Ford Museum. “It’s the greatest place on earth. And I’m not just saying that because it’s got my stuff,” says Gutman.

The Detroit-area museum, an assemblage of historic American artifacts, is no stranger to “Diner Man’s” unique passion. Curator of Public Life Donna Braden tells me it was Gutman who informed museum directors that a beat-up lunch wagon selling popcorn in the museum’s mock American town, Greenfield Village, was in fact the last horse-drawn lunch wagon in existence. Gutman oversaw the restoration project that restored the Owl Night Lunch Wagon to its former glory. He’s also responsible for Lamy’s Diner, a 1940s-era silver-and-blue diner-car he procured from Hudson, Massachusetts, which is now a functioning eatery within the museum itself that serves visitors diner classics from fluffernutters to malted milkshakes and breakfast doughnuts.

While his life’s work is in the process of being digitized and curated for the Henry Ford Museum, Gutman is left with his lingering habits. When I ask him when he stopped collecting memorabilia, he replies, “I never did.” Shortly after finalizing his donation, while at the famous Chuck Wagon Diner in Denver, he asked the waitress for a menu. When she offered him a takeout menu, he says he replied, “I need the real menu—it’s going to join others in my collection.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook