Meet The Black Cowboys Who Shaped Colorado History

The gunslingers, innovators, and explorers who carved their destinies from the sprawling promise of the West.

Willie Kennard wasn’t sure what to expect when he walked into the saloon across the street. He knew just two things: One, there was a wanted murderer inside. And, two, it was his job to arrest the man.

The year was 1874. Kennard had just ridden into Yankee Hill, Colorado—a small mining outpost near modern-day Idaho Springs—to inquire about a job posting for town marshall. But as soon as he did, the men hiring for the role burst out laughing.

Kennard may have been a retired soldier, an expert arms instructor, and one of the best gunslingers in the West, but they didn’t know that. To these men, Kennard was a stranger. And he was Black.

Kennard’s would-be employers wiped their eyes and smirked. After exchanging a few mischievous glances, they told him, sure, he could have the job—but he’d have to pass a test first. That test: arrest Barney Casewit, the bloodthirsty outlaw who had killed the previous marshall.

At that moment, they added, Casewit was playing poker across the street. Kennard shrugged. Undeterred, he strode over to the saloon, swaggered through the doors, and announced the arrest. Casewit stood up, reaching for a pair of pistols—but Kennard shot the guns straight out of the outlaw’s hands. Casewit’s two cronies jumped to their feet. With a flick of the wrist, Kennard took them both out with a single shot each.

He got the job.

Preserving Colorado History

Kennard became Colorado’s first Black marshall, but he was just one of many African American pioneers, explorers, and business masterminds who made their mark on the West. From James Beckwourth—a formerly enslaved person who became a fur trapper, trade liaison, and one of the first settlers at Bent’s Old Fort in La Junta—to Madam Walker, the first American woman to become a self-made millionaire, Colorado’s history is built on the genius and savvy of its Black residents. But over the years, many of these powerful figures have been willfully ignored by a majority-white power structure. That put them at risk of being lost to history altogether.

Enter the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center (BAWMHC). Established in 1971, the museum was the brainchild of Paul Stewart, a Denver barber and self-taught historian. Stewart started collecting Old West memorabilia and displaying it in his barbershop back in the 1960s. The shop quickly became an attraction for school groups and curious locals.

Daphne Rice-Allen, chair of the museum’s board of directors, remembers visiting the barbershop when she was young. Her mother taught Black history in the Denver public school system, and Rice-Allen would often tag along on field trips. She remembers what it was like to stand amid those artifacts, and gaze upon photos of the powerful figures who shaped the West.

“There was a lot of pride in being African American and in my history,” Rice-Allen says.

A Collection Grows

Stewart ultimately outgrew the barbershop and moved the museum into its own space. Today, you can visit his collection in a 1890s Victorian home in Denver’s Curtis Park Neighborhood. The house once belonged to Dr. Justina Ford, the first Black female physician in Colorado history.

Ford first moved to Colorado in 1901. Despite being barred from hospital practice due to her skin color, Ford spent 50 years serving her community out of her home. By the end of her career, she’d learned to speak to patients in seven languages and had delivered nearly 7,000 babies. She also paved the way for Black medical professionals in Colorado and beyond.

Today, Dr. Ford’s old home brims with historical treasures. Portraits cover the walls. Antique dressing tables hold 19th-century artifacts, and saddles and rodeo gear crowd the shelves. It’s an immersive experience that takes you back in time to one of Colorado’s wildest periods: 1865 to 1885, the era of the Black Cowboy.

The Real History of the West

“This was during the Black migration west,” Rice-Allen says. After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, hundreds of formerly enslaved people traveled west in search of a better life. Many of them found decent pay, camaraderie, and a sense of equality on horseback. “About one in four cowboys was Black,” Rice-Allen says.

At the time, one of the most significant Black cowboys was Bose Ikard. Ikard was born into slavery in Mississippi but moved to Texas post-emancipation. He quickly became a skilled rider and eagle-eyed tracker. Ikard rose through the ranks from ranch hand to cowboy to field detective for pioneering rancher Charles Goodnight (whose Pueblo home you can still visit today).

For years, Ikard drove cattle through Colorado along the 2,000-mile Goodnight-Loving Trail, riding through high country storms, tracking game, and clashing with Comanche warriors. During that time, Ikard was Goodnight’s right-hand man and a prominent figure on the ranching circuit. He worked alongside storied riders like Nat Love, rodeo stars, and famous outlaws alike.

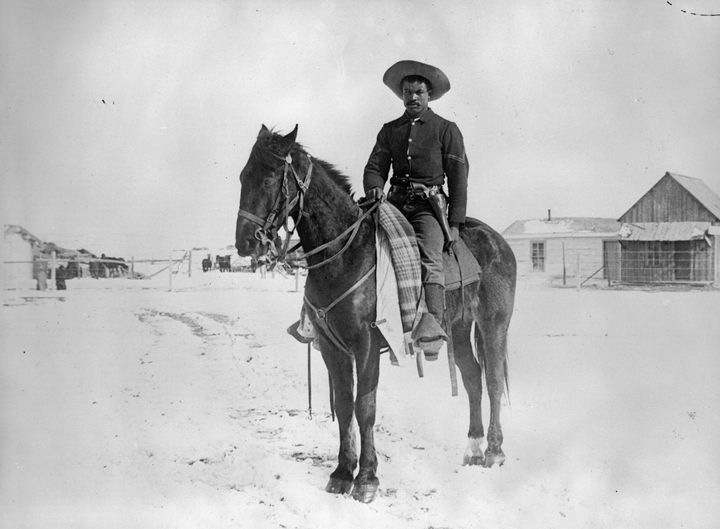

As Ikard was building his reputation, so was Willie Kennard. Kennard first learned to fire a gun when he enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War. After the war, he joined the 9th US Cavalry, an all-Black unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

“The Buffalo Soldiers were instrumental in the military,” Rice-Allen says. “They escorted wagon trains, assisted in the Indian War situation, and assisted in the later Range Wars.” By then, Kennard had gotten pretty good with a gun. So good, in fact, that his superiors promoted him to arms instructor. After a few years, Kennard decided to try something new. He moved to Colorado, arrested Barney Casewit, and became the town marshall of Yankee Hill. (While time has erased the town from the mountains, the hill itself remains accessible. You can get there via a scenic gravel-bike ride or hike from the charming mountain town of Idaho Springs.)

Later in life, Kennard moved to Denver, where he became the bodyguard of Barney Ford, the Denver restaurateur, hotelier, and gold prospector known as the Black Baron of Colorado. (You can still eat in the building that contained his historic People’s Restaurant in Denver, and visit a museum dedicated to him at his former Breckenridge home.)

Kennard may have also crossed paths with another, more enigmatic Buffalo Soldier: Cathay Williams. Born an enslaved person, Cathay Williams disguised herself as a man to enlist in the 38th Infantry, an all-Black unit, in 1866. The only known female Buffalo soldier, Williams served two years before her secret came out during a medical inspection for smallpox. She later settled in Trinidad, Colorado, where you can see a historic marker noting her influence on the town.

Bucket-List Destination

By the turn of the century, the era of the Black Cowboy and the Buffalo Soldier had come to an end, but the Jazz Age—and the era of Black wealth and influence in Denver—was just beginning. You can see artifacts from that era at BAWMHC, too, Rice-Allen says. Not much compares to wandering through those rooms, sinking through the decades of vibrant stories and daring figures. There’s a sense of pride and excitement, Rice-Allen says. It seems to seep through the very walls.

“It should be one of your bucket-list things to do next time you’re in Colorado,” she adds. “History is important, and Black history is a part of American history.” Of that, Colorado is living proof.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook