The Man Who Couldn’t Stop Buying Dinosaur Art

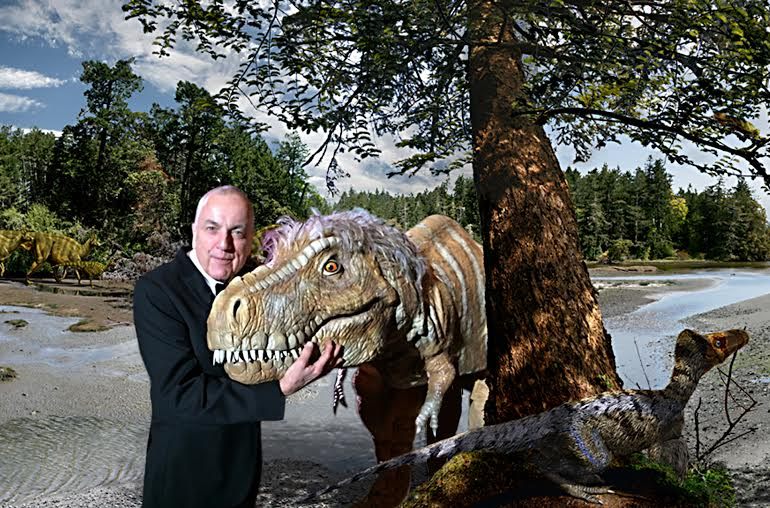

John Lanzendorf: hairdresser to the stars and unparalleled collector of dino art. (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

“At one time, I could name 700 dinosaurs,” says John Lanzendorf.

Lanzendorf, 69, is a hairstylist who has coiffed Chicago’s socialites for 51 years. He’s styled Rita Hayworth, Raquel Welch, Angela Lansbury and other celebrities. He is also an obsessive collector who amassed a staggeringly vast portfolio of dinosaur art. Once, his 1,250 square foot Chicago apartment was the Louvre of Terrible Lizards: Busts of long-necked Shunosaurus and Dicraeosaurus looked down upon massive sculptures of Tyrannosaurus rex and Stegosaurus. Bronzes of Dimetrodon and Triceratops commanded tabletops and floors. His collection roamed into every room.

“It got so big, I couldn’t turn around,” says Lanzendorf.

To a layperson, dinosaur art—or “paleoart“—may conjure up images of goofy roadside attractions or tail-dragging cartoons. But far from spinning out silly caricatures, the best-regarded paleoartists study current research and work with scientists to create the most accurate images of prehistoric animals possible. Without paleoartists, dinosaurs remain an assemblage of bones in the popular imagination. But despite a global fascination with dinosaurs, paleoart collecting was, and remains, rare. When Lanzendorf started stockpiling paleoart, word spread. Paleoartists started talking about the hairdresser in Chicago who was buying dinosaur art. They sought him out and offered him their works. Prolific and passionate, Lanzendorf soon assembled what is one of the largest—if not the largest —collection of dinosaur art in the world.

An example of paleoart by Donna Braginetz—Edmontosaurus and Maiasaura. (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

As a teenager in Spooner, Wisconsin, Lanzendorf knew he wasn’t meant to stay in a small town. When he couldn’t afford the senior class trip to New York City as a high school student, he boldly convinced the bus driver to take him as far as Chicago.

“They let me off on the expressway and I climbed up the embankment and got to my grandmother’s place,” says Lanzendorf. He had $35 and years of experience doing hair for his relatives and classmates. Three days after his arrival, he got a job as a stock boy and attended beauty school at night. He graduated at the top of his class and was soon employed as a hairdresser. Eventually he sought out and landed a spot at a top downtown salon. “And I became one of the most respected, well-known hairdressers in Chicago.”

The dinosaur obsession—as dinosaur obsessions often do—started in childhood.

“When I was a kid I got a dinosaur in a cereal box and I got hooked on that,” he says. “I used to eat a box of cereal every two days just so I could collect more dinosaurs.”

Tyrannosaurus rex vs Triceratops by Michael Trcic (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Tyrannosaurus rex vs Triceratops by Michael Trcic (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Lanzendorf might have become a paleontologist, but there was no money for college. Instead, starting in the mid 1980s, he started snapping up paleoart in volume. At his peak, he was collecting around one new artwork every week. He especially loved theropods—meat-eating dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex. (“I just love the shape of them and all that.”) He bought bronzes and paintings. Even salt and peppershakers. He acquired sketches from the 1800s.

His collection became a who’s-who of the paleoart world: Sculptures from Michael Trcic, lead animator of the T. rex in Jurassic Park, illustrations by James Gurney, author of the Dinotopia books, and works from innovative artists like Luis Rey, whose wildly colorful, feathered dinosaurs reflect the most up-to-date research.

Ornithomimid Theropod Dinosaurs by Donna Braginetz (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Ornithomimid Theropod Dinosaurs by Donna Braginetz (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Even without a formal education, Lanzendorf became something of a dinosaur expert, reading everything that he could get his hands on. He attended conferences. The renowned Canadian paleontologist Philip J. Currie invited him to a dig in Alberta. (Currie would later pen the introduction to a book about the collection, Dinosaur Imagery.) Eventually, museums began noticing his work:The first time the Lanzendorf Collection was displayed to the public was in 2000, as part of the Field Museum’s heralded unveiling of Sue, the largest and most complete T. rex skeleton ever discovered.

Meanwhile, dinosaurs were taking over Lanzendorf’s apartment.

Daspletosaurus Torosus by Michael Trcic (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Daspletosaurus Torosus by Michael Trcic (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

It was around this time The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis came calling. “When I first met John, he’s got a one bedroom apartment in downtown Chicago and it was wall-to-wall art,” says Dallas Evans, Lead Curator of Natural Science and Paleontology at museum. “You’d look at a wall and there’d be framed artwork, an inch to spare, and another artwork right beneath it, taking up the entire wall. In fact all the walls of the house, even in the bathroom.”

The museum wanted Lanzendorf’s collection for their Dinosphere. In 2001, they invited him on a trip to inner Mongolia. Evans and Lanzendorf toured around the fossil-rich country, visiting digs.

“I found a theropod tooth and a wooly rhinoceros metatarsus in the Gobi Desert,” Lanzendorf recalls. That same year, for an undisclosed amount, the museum bought his collection outright. The dinosaurs had outgrown his apartment and Lanzendorf was ready to move on: “Life is about change, I’ve learned that.” He kept his childhood toys and a Skrepnick painting of a Dimetrodon.

Evans has overseen the collection since its arrival.

“When I was first hearing about dinosaur art, I was a little skeptical, I expected it to be like black velvet Elvis paintings,” says Evans. But soon, Evans’ doubts evaporated, as he says that paleontologists and paleoartists have a symbiotic relationship. Art is often the best way to excite the public about a new discovery.

“Artists really rely on the scientist for guidance and technical experience but at the same time paleontologists are really in need of skillful illustrators that research new discoveries,” says Evans. “And it’s really often difficult for people to see fossils and relate to them as once living organisms, so art is great at communicating this across age, education and language barriers.”

The Lanzendorf Collection contains over 500 pieces and the museum doesn’t display it all at once, favoring themed exhibitions that are rotated out. Currently on display are unusual dinosaurs with flamboyant ornaments, such as Dracorex Hogwartsia (named for Harry Potter villain Draco Malfoy), an upright carnivore that looks like it’s wearing a football helmet studded in horns.

Evans can’t pinpoint an exact favorite in the collection, but he says he’s fond of the Trcic pieces. He does some fantastic very detailed work, there’s kind of a grace and fluidity to the dinosaurs and the sculptures,” says Evans.

Lystrosaurus by Gary Staab (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Lystrosaurus by Gary Staab (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

The museum continues to grow the collection, adding artworks that reflect the changing field of paleontology. Adding more artwork featuring feathered dinosaurs is a priority, according to Evans. There are other dinosaur art collections out there (the Smithsonian maintains a historical paleoart collection) but Evans is not aware of any that exist on such a grand scale.

Lanzendorf does miss his dinosaurs, but his legacy in the paleoart world is cemented. Once a year the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology awards the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize to artists in three different categories. And Lanzendorf has moved onto a new passion: Asian art. Sparked by the Mongolia trip, he now shares the same one bedroom apartment with an array of art gathered from India, Thailand, Mongolia, China and other countries. A 400-pound gilded bronze Buddha from the early 1700s resides in his living room where dinosaurs once ruled.

Lanzendorf also shares the apartment with his dog, Rafael Nadal, named for the highly ranked Spanish tennis player. Rafael is a Grand Basset Griffon Vendeen, a French breed that resembles a shaggy basset hound mashed up with a terrier. Popular in France, the dogs are rare in the United States.

“I’ve always liked unusual things,” says Lanzendorf, who still works four days a week as a hairstylist.

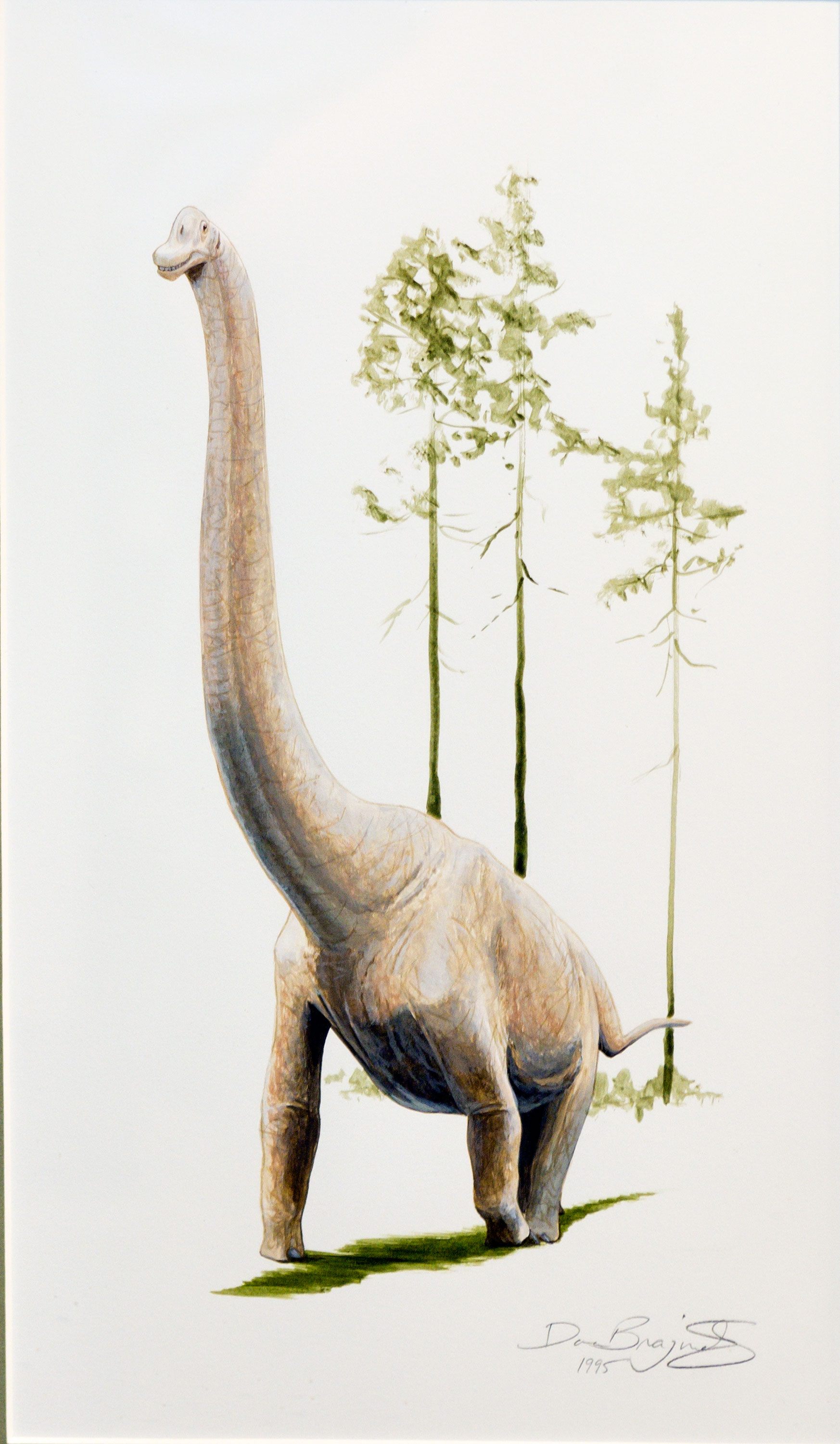

Brachiosaurus by Donna Braginetz (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

Brachiosaurus by Donna Braginetz (Photo: Courtesy The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis)

He once bred endangered parrots, sharing his apartment with ten of the birds. In the ‘80s he raised award-winning show cats, including Dr. Pepper, a Grand Champion Himalayan with snow-white fur and shocking blue eyes.

For now, Lanzendorf is content to amass more items for his Asian art collection. But he plans to graduate from that, too.

“I think I might go into dog art,” he says. “It’s become very popular in galleries on Madison Avenue.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook