Why Bear Fat Makes for Better Baking

This niche practice was commonplace in North America for centuries.

Hank Shaw bakes his buttermilk biscuits with bear fat. “The most breathless prose has always been reserved for bear fat in pastries,” writes the American chef, hunter, and outdoorsman. Melting much the same as pork, bear lard is used to make pie crusts, tortillas, popcorn, and more—and has been for some time.

While the technique is rare today, bear fat was a common ingredient for centuries, though one with a unique hangup. As with all omnivores, bears’ fat takes on the general flavor of their diet. In early fall, when nuts, berries, and acorns dot North America’s forests, Shaw writes, bear fat is “sublime … virtually indistinguishable from the finest pork lard you can buy or make.” The fat of blueberry-eating bears in Montana, for example, assumes sweet, fruity hints and a slight purple tinge. But if a bear most recently ate fish or suburban garbage, the lard takes on a briney odor that ranges from low-tide to truly vile.

This game of seasonal flavor roulette has relegated the practice of harvesting and rendering bear fat to a small subset of hunters and their families. “You hunt when the berries are out, you hunt when the nuts are out, but most people don’t know any better,” says Shaw. Bear fat wasn’t always this fringe; but then again, it wasn’t always food, either.

Bear fat was once the Swiss army knife of North America. Native American tribes variously used it to weatherproof knives and bows, moisturize drum hides, straighten their hair, and repel insects. In the 19th century, European settlers brought to the Americas the belief that bear grease effectively treated hair loss. In London, John George Wood wrote in 1856, “it was the custom for … hairdressers to keep bears on their premises.” Many Londoners, he adds, paid for the privilege of rubbing their heads on the bear’s body, so as to ensure they got real bear grease. The Apaches used bear fat in glass jars to predict the weather, a practice handed down to G. Gordon Wimsatt, the “Bear Grease Kid,” who, in the mid 1900s, used it to forecast more accurately than the days’ leading meteorologists.

The versatility and abundance of black bear made it a key part of the food supply as well. Dr. Michael Wise, Director of the University of Texas Food Studies Program, says cooking with bear fat was widespread throughout North America until the mid- to late-19th century. He points to French Louisiana colonists who incorporated American ingredients to mimic European dishes. As one Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny wrote in the 1720s, his company rejoiced in dressing a green salad with bear fat and oak sap, or crafting a bear fat roux. Tougher bear fat could be melted and poured over game meat in bags for frontier preservation. (“Kind of like saran wrap,” says Wise.) Daniel Boone established a veritable bear enterprise in Kentucky throughout the 1790s, selling the meat, hide, and oil from 156 bears in one season.

Urbanites ate their fair-share of bear as well. At an honorary dinner thrown in Manhattan for Charles Dickens and 3,000 guests, the entrée was roast leg of bear, according to Four Pounds Flour. At the time, bear was a high-end delicacy sold throughout urban markets and restaurants. Eating bear remained in the American lexicon well into the 20th century, with recipes appearing in popular cookbooks. Together with its profitable pelt, bear fats’ mishmash functionality nearly decimated North American populations by 1900.

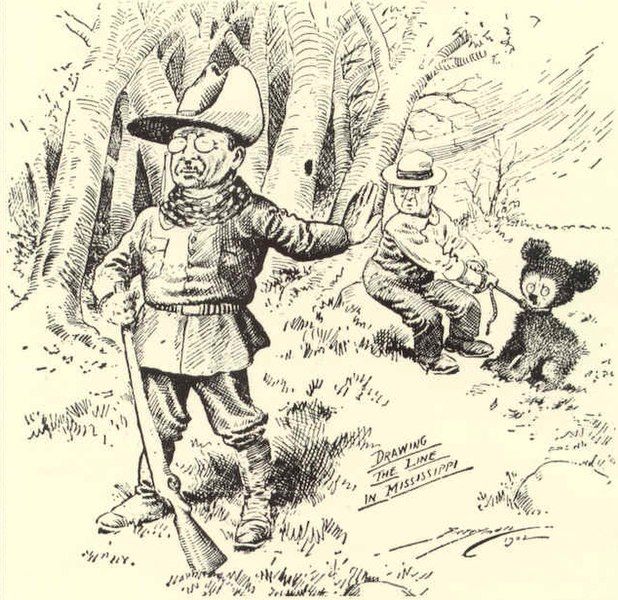

Luckily, North Americans began to rethink their ursine approach. “Around the turn of the last century, bears in general moved [out of the] food bucket in [our] imaginations to something else,” says Shaw, “in no small part thanks to the advent of the teddy bear.” The story goes that mid-way through a luckless hunt in the early 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt’s aides caught and stunned a bear that they left tied to a tree for an executive dispatch. After Roosevelt spared the dazed bear, cartoonists fell over themselves recreating the event, and one New York toy store capitalized on the sensational pardoning, creating the inaugural “Teddy Bear.”

The period also witnessed a shifting American agricultural landscape that saved the bears from extinction. Food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson writes that as frontier areas became settled farmland, bears relocated to underpopulated areas while demand for their meat and fat deflated. “Why go bear hunting when you could raise beef, pork, and chicken (and their requisite fats)?” she asks. This newfound access to domesticated animal protein also led game animals such as woodchuck, possum, and raccoon to fall quickly out of favor. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 groundswell novel The Jungle, writes Johnson, emboldened vegetable-oil companies to slander meat byproducts, further contributing to a decrease in demand for game fat.*

Simultaneously, national legislation pushed by conservationists banned the commercial sale of game animals and regulated the hunting of at-risk species. Thanks to the clampdown on market hunting, bear populations stabilized throughout the 20th century. Bear meat and fat was supplanted by cheap and consistent factory animals, and knowledge surrounding the rendering of bear fat slid into obscurity.

Today, the American black bear is categorized as a species of “least concern” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Some 900,000 black bears roam the forests of North America, covering 40 of the 50 United States. An audacious display of their return came in the 1990s, when a young group of bears in Southern California began ambling nightly down from Los Padres National Forest to gorge themselves on the avocado orchards below. As the bears hardly put a dent in seasonal yields, the owners welcomed the feeding, naming the perpetrators “Guacamole Bears.”

New Jersey, home to the densest population of bears, resumed issuing annual bear hunt permits in 2010. Despite releasing a “Black Bear Recipe Guide,” the state saw twice as many black bears born in 2017 as were hunted. Populations have doubled in Florida since 2002, and in Canada they’ve reoccupied 95 percent of the lands they once roamed. “American black bears are doing well all over,” Harry Spiker told National Geographic.

While the bears have rebounded, the secret of cooking with their sweet, velvety fat did not. “You tell someone you’re bear hunting and they look at you funny,” says Shaw. The nose-to-tail movement, which focuses on cooking every part of the animal for culinary and environmental reasons, did elicit a resurgence in hunting over the last 10 years, Shaw tells me over the phone from a hunting-training program in Texas. But many bear hunters and guides, not knowing when to hunt bear for fat that tastes delicious rather than disgusting, tell people to cut it all off.

Today, the practice of rendering bear fat is survived by the few in the know. He’s yet to try it, but Shaw has heard that the fat of Guacamole Bears is “legendary.”

*Correction: This post previously stated that Upton Sinclair’s novel “The Jungle” was published in 1937. It was published in 1906.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook