Centuries Later, America’s First Female Botanist Lives On in a Community Garden

Jane Colden defied gender barriers to become an early expert in Linnaean taxonomy.

In 1728, the young Jane Colden moved with her family to a plot of land in the Hudson Valley that, according to her father, was populated less by people and more by “wolves, bears, and other wild animals.” Much of colonial New York was forested back then, and the overgrown landscape would become Colden’s office as she worked as a prolific amateur botanist, drawing and describing 400 species of plants that grew in her (relatively sprawling) backyard.

Though she spent her entire life isolated in this rural area, her work was recognized internationally, particularly by naturalists in the United Kingdom such as John Ellis, Peter Collinson, and the aptly named Alexander Garden. Today, Jane Colden is commonly acknowledged as the first female botanist in what would become the United States, noted for her forward-thinking adoption of the relatively new Linnaean taxonomy.

Colden was born in 1724 in New York City, but her family soon abandoned urban life for Orange County, New York, notes Anna Murray Vail in her 1907 paper “Jane Colden, an Early New York Botanist,” published in the journal Torreya. In the country, her politician father could pursue his varied extracurricular interests, including botany.

Jane’s father encouraged her to study the numerous species of plants that grew on the family’s 3,000 acres of wilderness. He had just learned of a newfangled system of categorizing plants, devised by Carl Linnaeus, and was eager to impart his knowledge—even if his reasons for introducing his daughter to the field were slightly condescending. “I thought that botany is an amusement which may be made agreeable for the ladies who are often at a loss to fill up their time,” her father once wrote. Under her father’s tutelage, Jane soon became an expert on Linnaean botany.

Before the 18th century, the field of botany was kind of a mess. Identification often involved monikers from the Middle Ages, steeped in religious significance and anything but uniform. So when Linnaeus introduced a system of taxonomy in which each specimen received two Latin names, the first designating the genus and the second the species. With this system, Linnaeus transformed scientists’ knowledge of plants into a universal system.

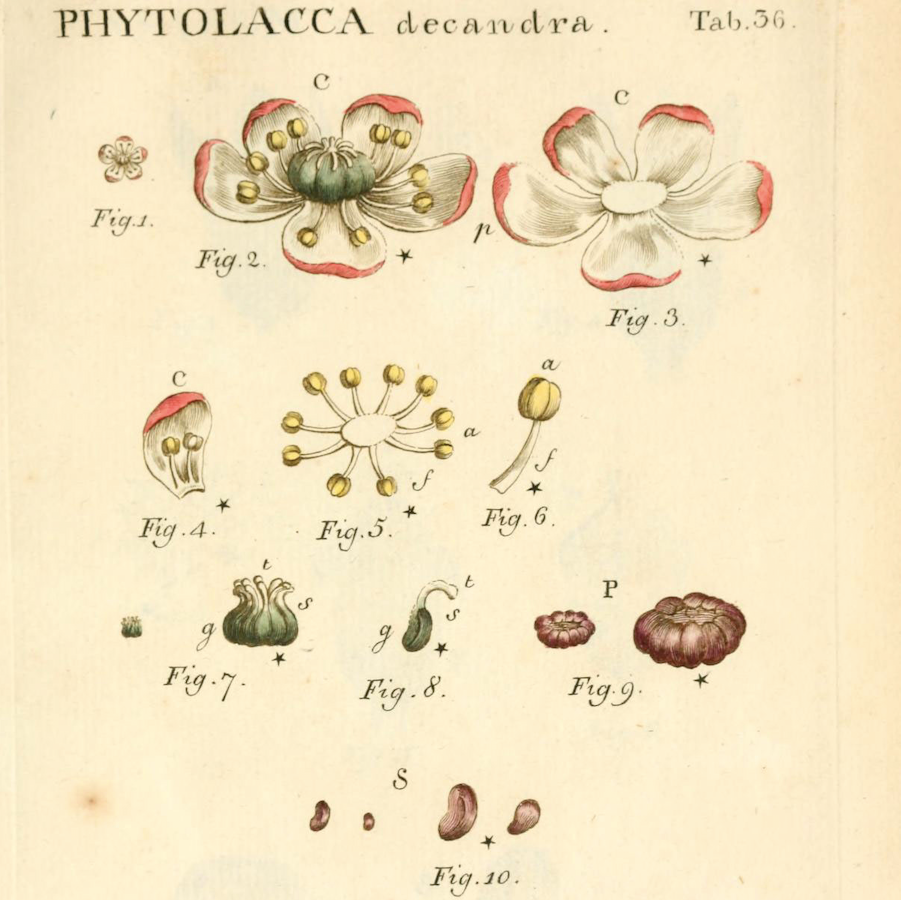

Key to Linnaeus’s system, however, was the division of plants into two genders, male and female. He established 24 classes based on the number of male stamens in the flower, and then subdivided each class into subordinate order based on the number of female pistils. He devised lengthy metaphors that conflated plant and human reproduction, analogizing various parts of a flower to human reproduction in Philosophia Botanica.

This categorization system was scientifically innovative and culturally taboo. Suddenly, botany had become the most explicit public discourse on sexuality in the mid-18th century, writes Caroline Jackson-Houlston in “Queen Lilies’? The Interpenetration of Scientific, Religious and Gender Discourses in Victorian Representations of Plants.” The open discussion of sex between, well, plants, erected another barrier for prospective female botanists, as the field now suggested a problem of sexual decorum, Jackson-Houlston writes. (In 1895, the pioneering feminist Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy would reappropriate this sexualized language in her botany primer Baby Buds, which doubled as a sex-education handbook at a time when talking about such things was wildly taboo, The Atlantic reports.)

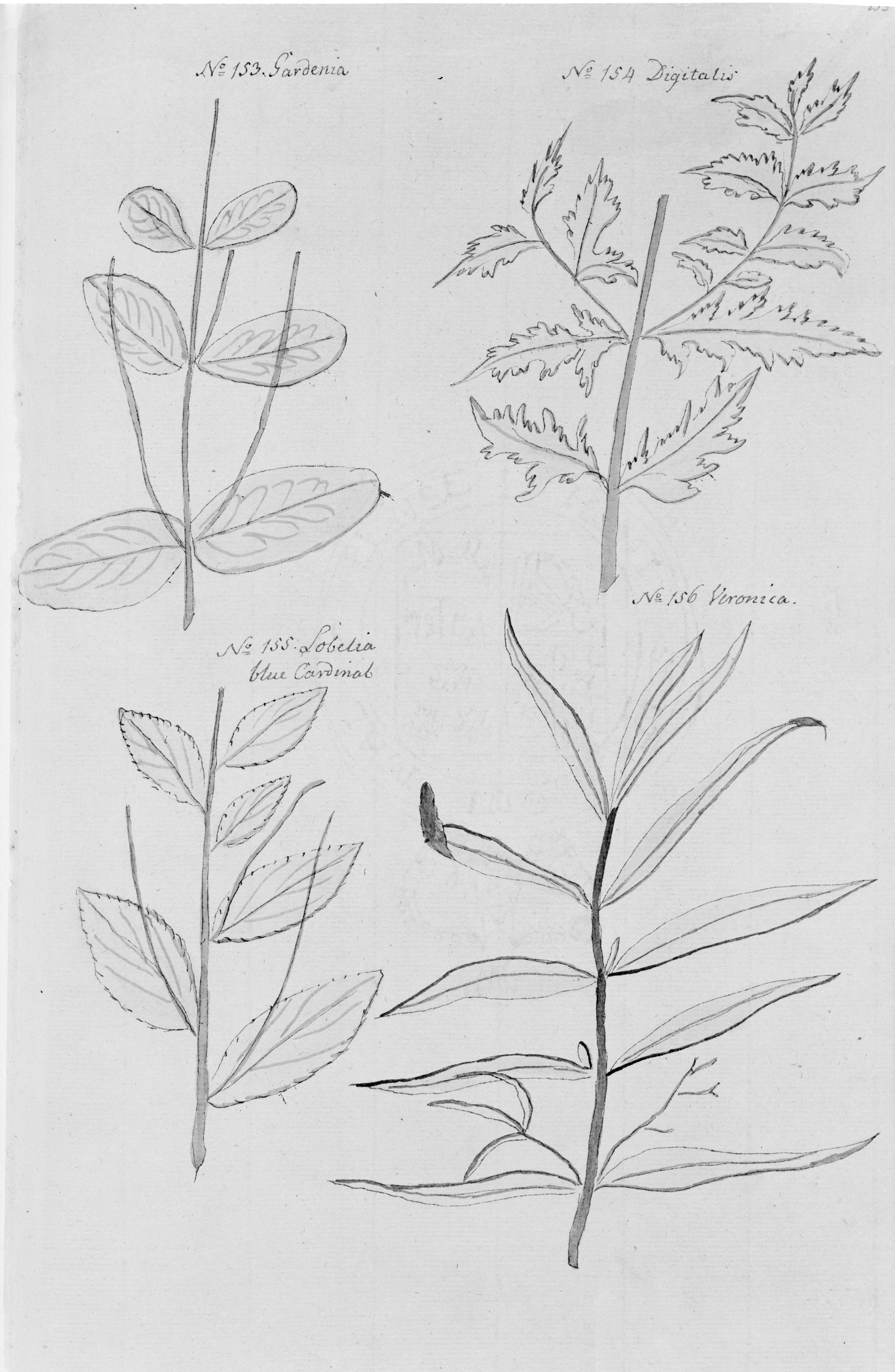

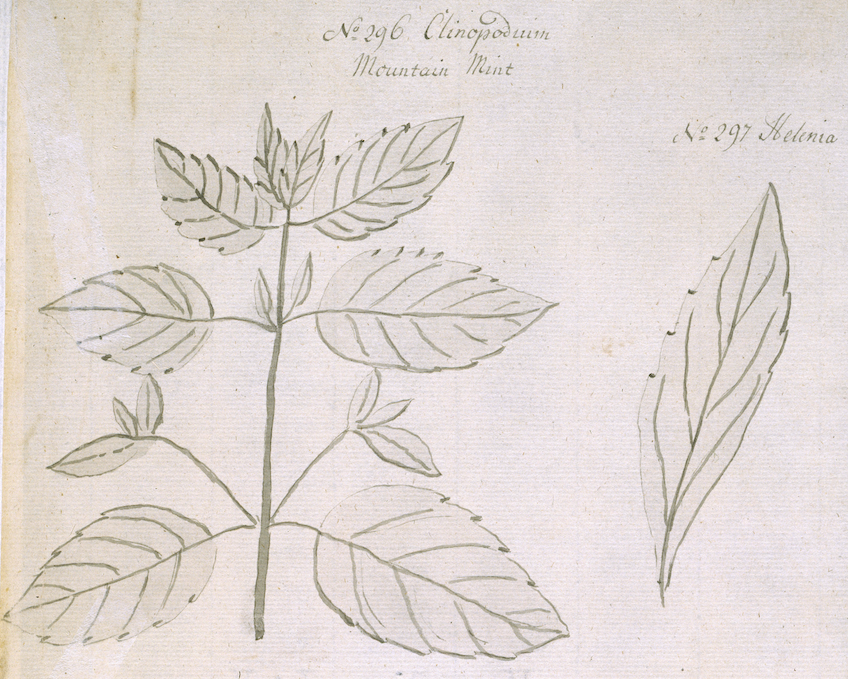

In 1753, Colden gave herself the mission of sketching and classifying all the plants that grew in her family estate with the Linnaean system, according to Vail. She saw her work as an extension of her father’s more modest paper on the plants. She documented each in painstaking detail, accompanying each entry with a print rubbing or line drawing of the sprout in question.

Unlike most male botanists of the day, Colden noted the practical uses of each plant in medicine and cooking, and even attributed these details to the country people or local indigenous people who taught her. She described hundreds of plants without venturing beyond her family’s acreage, as the French and Indian War made travel dangerous.

Colden compiled her illustrated volume of New York’s plants for five years. During that time, her father wrote to leading botanists including John Bartram, Collinson, and Garden, often including specimens she found. The botanists soon grew acquainted with her work and respected her as a peer. Bartram even visited Colden, who took him out seed-hunting after dinner.

In 1758, Colden completed her untitled manuscript, which would later be called “Flora of New York.” In rich, meticulous descriptions, she noted the morphological details of flowers and fruits as well as their practical uses. Despite the limited educational opportunities afforded to women in the 18th century, it was clear Colden had become an early expert in the flashy, burgeoning field of Linnaean taxonomy.

In the final years of her project, Colden did hone one other notable accomplishment. As one visitor wrote, “She makes the best cheese I ever ate in America.” Colden compiled a record of her many cheeses in a folio she called the “Memorandum of Cheese made in 1756.”

Despite repeated attempts, many supported by her male allies, Colden never managed to have a species named after her. In 1758, John Ellis informed Linnaeus himself that he believed Colden had described a plant that was colloquially known as goldthread, and suggested that it be named in her honor, Vail writes. “Suppose you should call this Coldenella, or any other name that might distinguish her among your Genera,” he wrote, adding that Colden had described 400 plants under his own taxonomy. Linnaeus declined to recognize the species in a new genus, a decision that was later reversed by Richard Anthony Salisbury, who chose the name Coptis. Colden’s father, however, did have a genus named after him—Coldenia.

In 1759, Colden married William Farquhar, a Scottish physician, and stopped producing her botanical manuscript. In 1766, at the age of 41, she died in childbirth along with her first child. “Flora of New York” disappeared for a decade after her death, until a Hessian forester and botanist noted that it had come into his possession. After passing through the hands of several more men, the volume went to the British Museum in Kensington, London in the mid-1800s.

In 1957, in Colden’s hometown of Orange County, the Garden Clubs of Orange and Dutchess Counties constructed the Jane Colden Memorial Garden at Knox’s Headquarters State Historic Site, according to Michael McGurty, Knox’s site manager. The volunteers only planted native species that Colden described in her book, such as the delicate shrub spicebush shrub, the three-petaled trillium flower, and the distinctive hooded flower Jack-in-the-Pulpit.

Because the garden is essentially a volunteer project, it’s gone through phases of dereliction, according to Chad Johnson, the interpretive programs assistant. Starting in the 1960s, it was almost entirely tended by a woman named Dorothy Shreve. But by the early 90s, in large part due to aging volunteers and the economic recession, the garden was good as abandoned. But in 2014, John Hunter, a retired local superintendent, revived the garden. “It was an overgrown bramble full of Floribunda roses and raspberry bushes,” Hunter says. “We lost a few pints of blood yanking those out over a year or two.”

In the past few years, Hunter and another volunteer, Ed O’Connor, have uncovered and replanted many species that grew in the original garden, including trout lilies and Virginia bluebells. It’s an ongoing project, he says, and they’re always looking for help.

The garden is open to visitors during Knox’s Headquarters’ usual operating hours, from May 23 to September 2. “It’s less impressive than it sounds,” Johnson says over the phone. “It’s not a formal French garden or anything. It’s more of a nature walk, with plants that are best admired up close,” he says. “But that feels right for Jane.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook