The Lucrative Business of Prescribing Booze During Prohibition

Those looking to self-medicate could score at the doctor’s office.

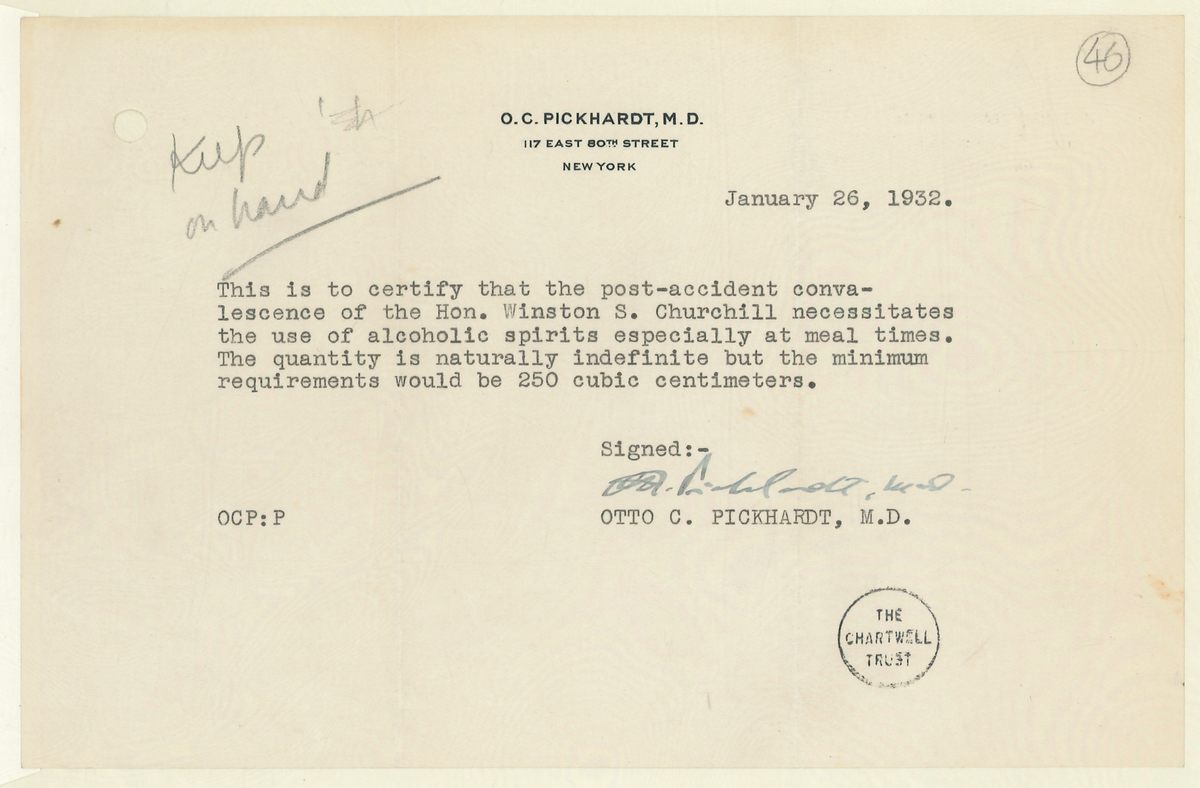

On December 13, 1931, a car zipping along Fifth Avenue in New York City rammed into Winston Churchill. Churchill, in town to give a lecture at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, had looked to his right instead of his left while crossing the street (a habit—traffic in England came from the left). The accident cut Churchill’s nose and forehead, bruised his chest, and left him with a sprained shoulder. “I do not understand why I was not broken like an egg-shell or squashed like a gooseberry,” he later wrote.

The press described the injuries as minor, but for months following the accident, Churchill privately battled depression and pleurisy, a condition that causes sharp chest pains. And Churchill, a prodigious drinker on a lecture circuit in Prohibition-era America, couldn’t exactly guzzle the pain away. Buying alcohol was illegal—until he got a doctor’s note. His physician, Dr. Otto C. Pickhardt, wrote that “the post-accident [recovery] of Hon. Winston S. Churchill necessitates the use of alcoholic spirits especially at meal times.” Specifically, Churchill required a “naturally indefinite” quantity of booze.

While it’s unclear how Pickhardt swung Churchill’s indefinite amount of booze, he wasn’t the sole doctor to dole out alcohol during this dry era. Thousands of doctors, veterinarians, pharmacists, and dentists held permits authorizing them to prescribe select quantities of rye whiskey, scotch, and gin for a bevy of conditions including cancer, anxiety, and depression. According to Daniel Okrent, author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, some 15,000 doctors applied for permits during the first six months of Prohibition, which began in 1920 and lasted through 1933. Yet due to a lack of federal oversight, pharmacists and physicians easily turned what was meant as a merciful concession into a lucrative loophole. By prescribing access to pharmacies stocked like liquor stores, it allowed them to become wealthy by selling a way out of Prohibition.

Prescribing alcohol during Prohibition wasn’t pure corruption—alcohol’s alleged medicinal uses have been traced as far back as ancient China, Rome, Egypt, and Greece. One 17th century-era recipe from Great Britain advised melding two pints of wine, along with sage and rue, to concoct an “excellent drink against the plague.” Dozens of 19th century-era physicians believed that alcohol prevented infectious diseases and fever, and that it spurred internal, “vital powers” that kickstarted the healing process.

Initially, many doctors joined the coalition of preachers, former abolitionists, and suffragists pushing Prohibition. In 1916, the authors of The Pharmacopeia of the United States of America took two liquors, brandy and whiskey, off the list of scientifically approved medicines. And in 1917, the American Medical Association voted to advocate for prohibition. In their statement, they wrote that “the use of alcohol is detrimental to the human economy and … its use in therapeutics as a tonic or stimulant or for food has no scientific value.”

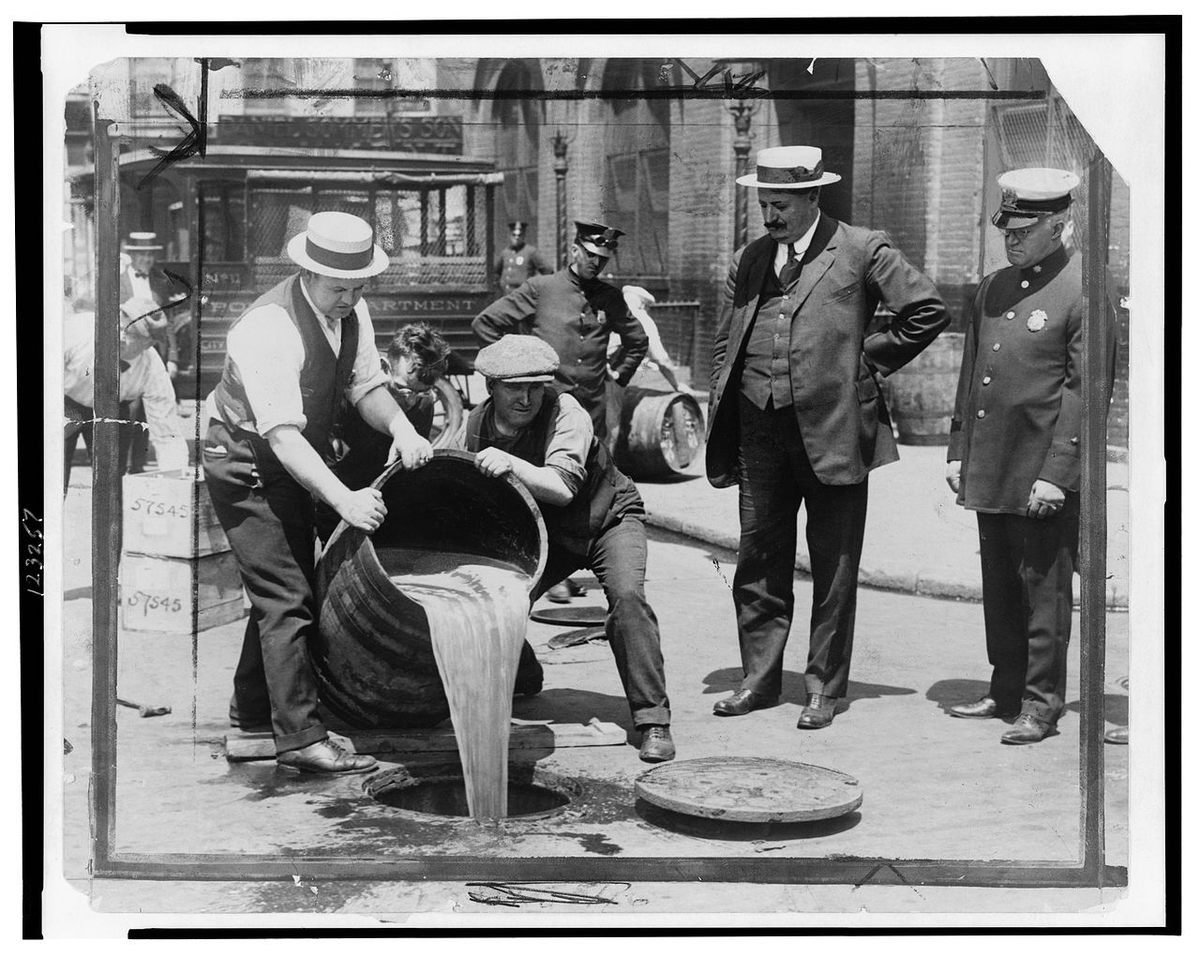

In 1919, Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment, which banned the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol. Prohibition went into full effect on January 16, 1920, and agents wasted no time in dramatically seizing alcohol. Agents in New York City poured barrels’ worth of beer down the drain, while Boston’s pedestrians walked foot-deep in smashed glass and liquid.

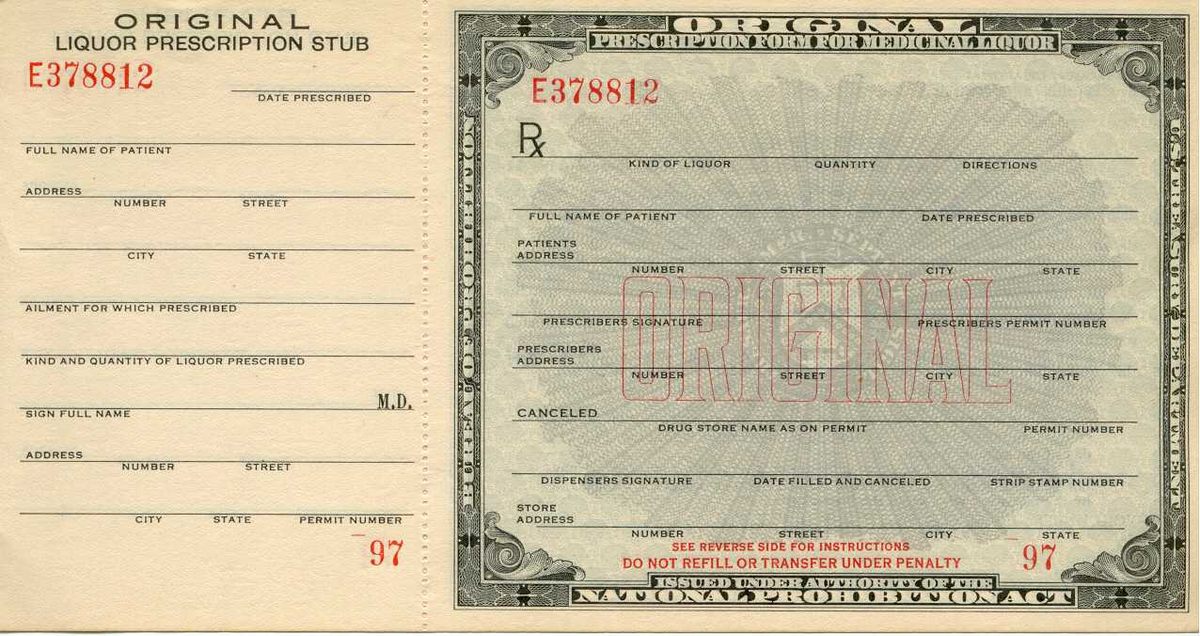

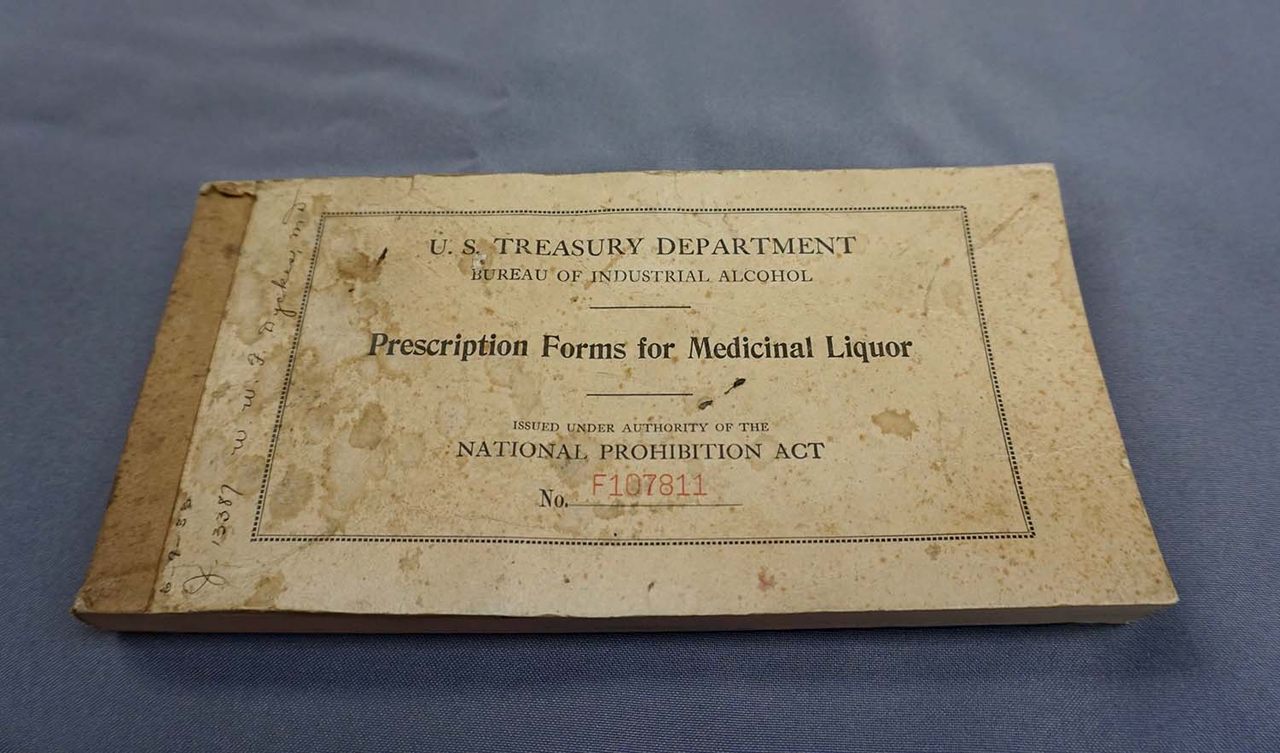

Still, when the nation went dry, doctors found themselves among the select few who could still legally access and distribute alcohol. The accompanying National Prohibition Act (also known as the Volstead Act) allowed clergymen to use wine for sacramental services and farmers to possess up to 200 gallons of preserved fruit. Doctors, meanwhile, could apply for licenses that gave them the ability to write scripts for medicinal booze. Patients could then ask for the drink of their choice at pharmacies—not unlike going to a marijuana dispensary with a doctor’s note today.

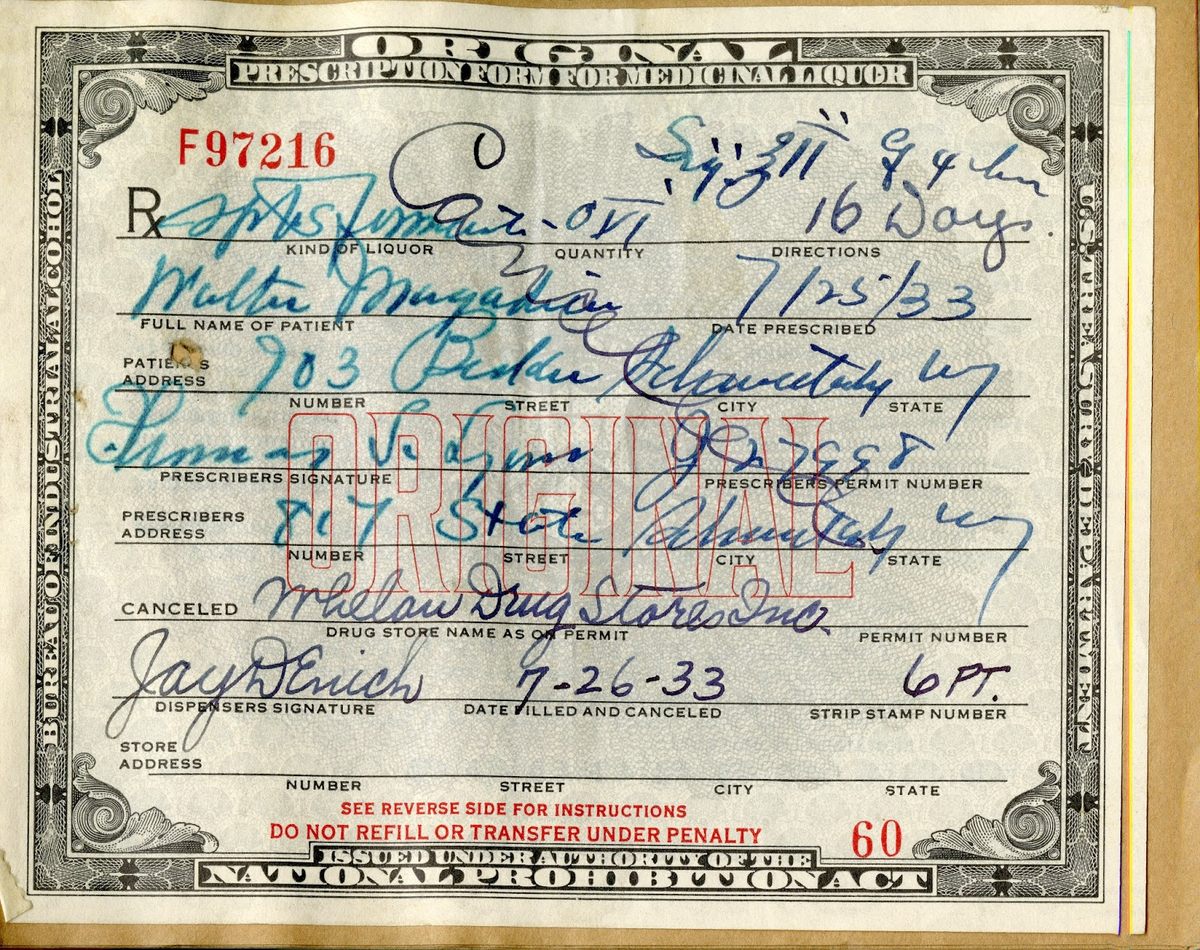

Congress did write safeguards into the law. It dictated that patients couldn’t obtain more than a pint of “spirituous liquor” every ten days, and that prescriptions couldn’t be filled more than once. Prohibitionists successfully pushed for even more restrictions, too. The 1921 Willis-Campbell Act (colloquially known as the Emergency Beer Bill) banned prescriptions of beer. It also lowered the cap on alcohol per prescription (from a pint to a half-pint) and limited physicians to 100 prescriptions every 90 days. Following the bill’s passage, doctors typically wrote a script every ten days for a half pint of alcohol.

Yet as The Washington Post notes, enforcement in the early years practically didn’t exist, and by 1921, dozens of physicians and pharmacists (who filled the orders) had gotten hip to the law’s money-making potential. Some watered down alcohol, while others doled out heavy-handed prescriptions. During Prohibition’s first year, doctors prescribed an estimated eight million gallons of medicinal alcohol—or, 64 million pints. Doctors got away with prescribing more than the legal limit due to loopholes and lax enforcement. The Willis-Campbell Act tightened the rules, but, by still recognizing doctors’ ability to use alcohol as medicine, left loopholes open. Doctors could issue looser prescriptions by showing (as in cases like Churchill’s) “that for some extraordinary reason a larger amount is necessary.”

From there, doctors had their work cut out for them. While physicians technically had to supply the government with their patient list, it didn’t require them to be specific about treatments. Which is why one Providence, Rhode Island, physician merely listed the catch-all term for a physical weakness, “debility,” on his ledger to justify pints of rye. And they could get away with it, partially because they vastly outnumbered the government agents who kept tabs on them. According to the Post, only one agent existed per 300 physicians in New York City. Nearly 700 new, New York City drugstores registered between 1921 and 1922, and the Board of Pharmacy didn’t have the resources to investigate if they were legit. So the 64,000 physicians given liquor-prescribing permits from 1920 to 1926 didn’t have much to worry about. A mere 170 physicians per year, on average, had their licenses revoked.

Given the low risk, many druggists and physicians started price-gouging patients. As Okrent writes, physicians’ prescription power during Prohibition became a way for them to line their pockets. The number of licensed pharmacists tripled in New York, and it’s not hard to see why. Obtaining a permit to fill prescriptions didn’t take much effort, and they could charge extortionately. In Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era, J. Anne Funderburg writes that mere weeks after Prohibition came into effect, Brooklyn pharmacists charged $12 for a pint of whiskey—over $150 by today’s standards.

While the medical community debated alcohol’s alleged medicinal uses, many physicians all but encouraged people to drink. One anecdote in Okrent’s book recounts a Detroit physician who encouraged patient to “take three ounces every hour for stimulant until stimulated.” Physicians wrote an estimated 11 million prescriptions a year throughout the 1920s, and Prohibition Commissioner John F. Kramer even cited one doctor who wrote 475 prescriptions for whiskey in one day.

It wasn’t tough for people to write—and fill—counterfeit subscriptions at pharmacies, either. Naturally, bootleggers bought prescription forms from crooked doctors and mounted widespread scams. In 1931, 400 pharmacists and 1,000 doctors were caught in a scam where doctors sold signed prescription forms to bootleggers. Just 12 doctors and 13 pharmacists were indicted, and the ones charged faced a one-time $50 fine.

Selling alcohol through drugstores became so much of a lucrative open secret that it’s name-checked in works such as The Great Gatsby. Historians speculate that Charles R. Walgreen, of Walgreen’s fame, expanded from 20 stores to a staggering 525 during the 1920s thanks to medicinal alcohol sales. (Walgreen attributed the pharmaceutical empire’s massive expansion to the introduction of milkshakes at its stores.) According to Okrent, it’s also how distilleries in middle America, particularly in Kentucky, kept the lights on during Prohibition.

Medicinal alcohol wasn’t exactly affordable, meaning that the loophole was a luxury reserved for wealthier Americans. Prescriptions ran patients three dollars—the equivalent to $40 today—and another three or four dollars to fill them. Authorities curiously allowed French champagne to be imported for medicinal use, which upper-crust Americans took advantage of: Imports skyrocketed by 332 percent in 1920. Industrious Americans decided to make alcohol for themselves, too, using corn syrup to make millions of gallons of moonshine supplied to drinking clubs and speakeasies. More adventurous patrons clandestinely ducked into speakeasies, with the understood risk that the mystery booze might contain industrial alcohol used in medical supplies.

Prohibition ended with the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1933, and so did the era when a doctor’s note could get you hooch at the pharmacy. Yet Prohibition didn’t do what it intended, which was to stop drinking. As Oxford University Press notes, alcohol enthusiasts drank more hard liquor during Prohibition than before, and spirits accounted for a staggering 75 percent of all alcoholic beverages consumed in the United States. (Ironically, alcohol consumption pre-Prohibition had been gravitating towards beer.) The era unwittingly became the foundation of contemporary American drinking culture, giving birth to libations including mixed drinks, bathtub gin, and moonshine. Some might say that’s just what the doctor ordered.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook