Election Fraud in the 1800s Involved Kidnapping and Forced Drinking

How roving “cooping” gangs got voters drunk and disturbed the democratic process.

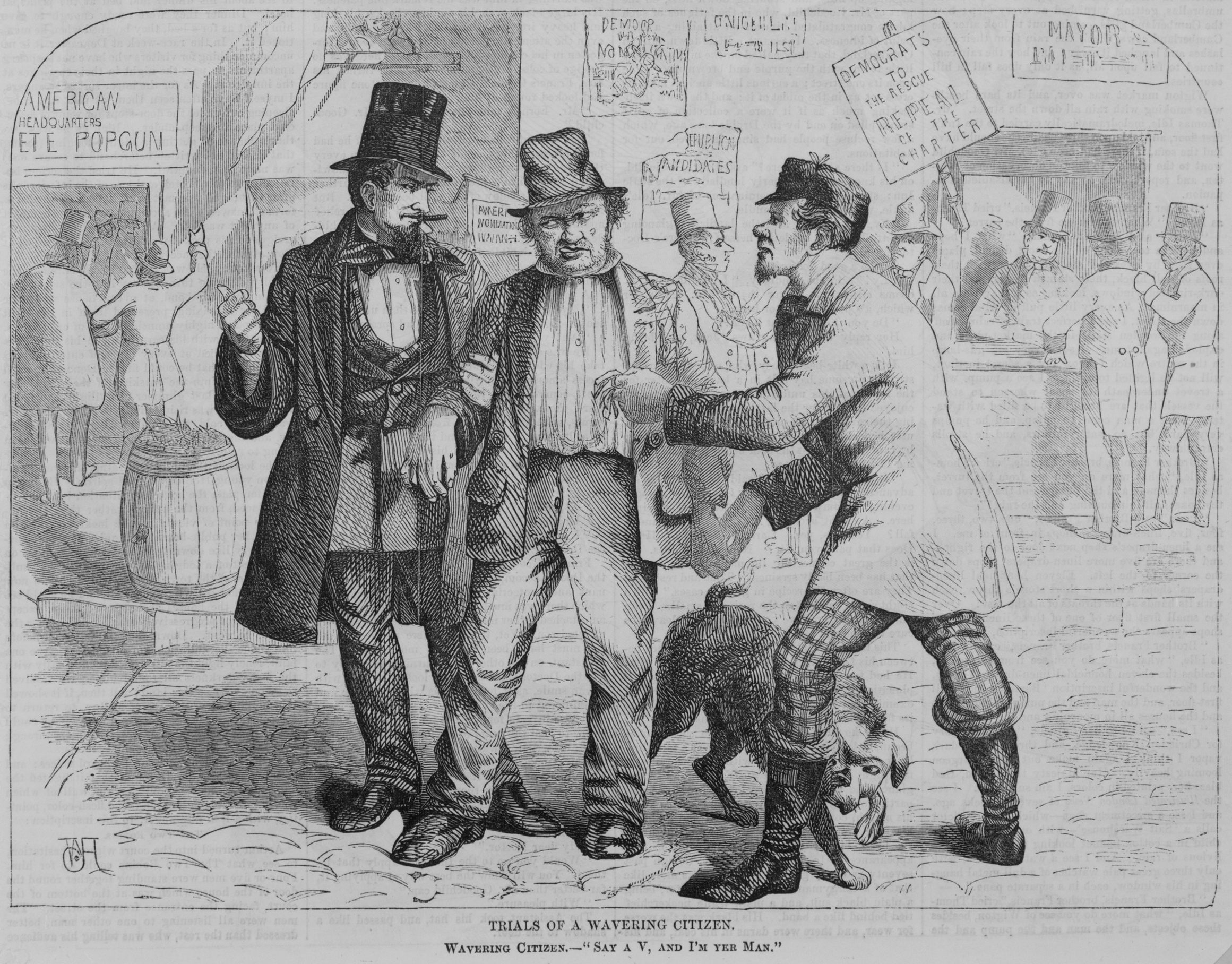

A depiction of politicians trying to buy votes from an 1857 Harper’s Weekly. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-118006)

This summer Donald Trump stoked fears that rampant voter fraud could hurt his chances in the 2016 presidential election even as federal courts were striking down voter-identification laws in several states, with a judge in Wisconsin rejecting what he called “a preoccupation with mostly phantom election fraud.”

Those concerns stem from the very real voting fraud schemes of the 19th century, when political parties employed tactics more often associated with pirates and human-trafficking gangs. Before sophisticated computer models were used to get out the vote, violent gangs would kidnap voters, feed them alcohol or drugs and force them to vote multiple times dressed in various disguises. Known as “cooping,” this was a common strategy to ensure a win on election day.

In the 1800s, United States elections were rife with fraud, and political parties were more like private clubs than the bureaucratic representatives we have today, so cooping fit right into politics of the time. A book on the history of Catholicism in the United States says that “the practice of “cooping” voters on election day was quite common,” and campaign gangs who corralled voters were, according to one definition, “wining and dining [victims] till they “vote” according to wishes of the “Coop-manager,” disrupting the American voting process.

George Caleb Bingham’s 1846 painting The County Election, depicting a polling judge and voters, some of whom are drunk. (Photo: Public Domain)

While the public was aware of and disgusted by cooping, it was so ingrained in American politics that it continued through the end of the 19th century. In 1842, Washington’s Weekly Globe wrote that the “Federalist Party in the United States, during the last presidential election, introduced all these contrivances” supposedly in lieu of the United Kingdom’s cooping schemes, which included “bribing, thumbing, bullying, and the abduction of voters, steeped in drunkenness.” One report in the same article even claims that 300 voters were, according to some witnesses, transported away to different countries to keep them from voting in local elections.

Many cooping victims were immigrants. As naturalization was formalized for the influx of European immigrants in the mid-1800s, new citizens were eligible to vote in the United States, along with most free white men (at that time all women, and men of color, were not). Americans born in the U.S. viewed the immigrant votes as a threat, and would coop immigrant voters in undisclosed locations to keep them from voting—or force them to vote for candidates supported by the gang.

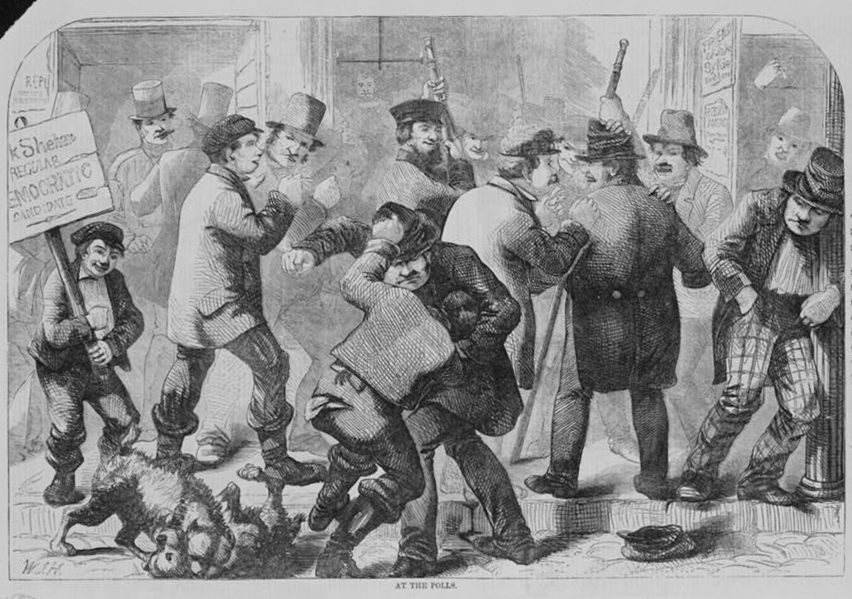

Fights at the election polls, 1857. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-118012)

Cooping victim J. Justus Ritzmin was looking for a laboring gig when he was lured by cooping campaigners during the 1859 presidential election in Baltimore, Maryland, which was later examined in a lengthy congressional hearing on the fraud. A member of the Pug Ugly street gang offered Ritzman and other men a job, and then brought them to a bar. When fully drunk, they were led into a warehouse, where they “came in front of a crowd of men, about five or six, armed with clubs, and guns, and other weapons,” according to Ritzman’s testimony in court in 1860. The men were robbed and left in a dark basement, where they were given voting tickets for the Democratic candidate.

He and the others voted 16 times that day. Peter Fitzpatrick, another cooping victim, said the gang “dealt me two blows with a billy on the head and two on the knees, to make me drink liquor; and after they compelled me to drink.” On voting day, they and almost 80 other men were forced to one polling booth after another, changing jackets and hats between stops as a disguise. “The treatment of some of those in the coop was disgusting and horrible in the extreme; men were beaten, kicked and stamped in the face with heavy boots,” said Ritzman.

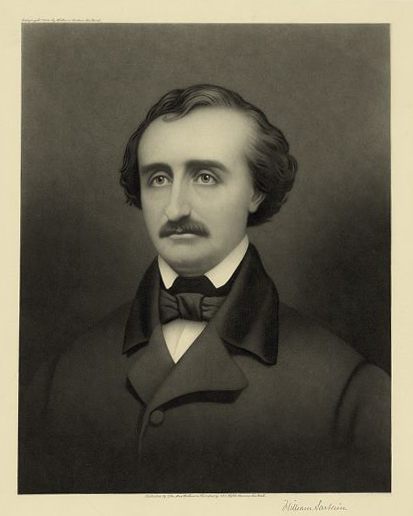

Edgar Allan Poe, rumored to have died in a cooping incident. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-pga-04119)

Votes were easily manipulated by gangs at the time: voter’s lists and pre-registration in the 1800s were hard to track by hand, and voting wasn’t particularly private. Before the election began, voters would collect highly-visible, labeled voting tickets for a candidate, stand in line, and give their tickets to a ballot officer at their local polling place. Often, it was impossible to figure out who had voted when or where, and some candidates hired gang members as voting marshals to oversee elections. The phenomena was so rampant that some biographers of Edgar Allan Poe ascribe his death to a cooping incident during a Baltimore election, though this is not confirmed.

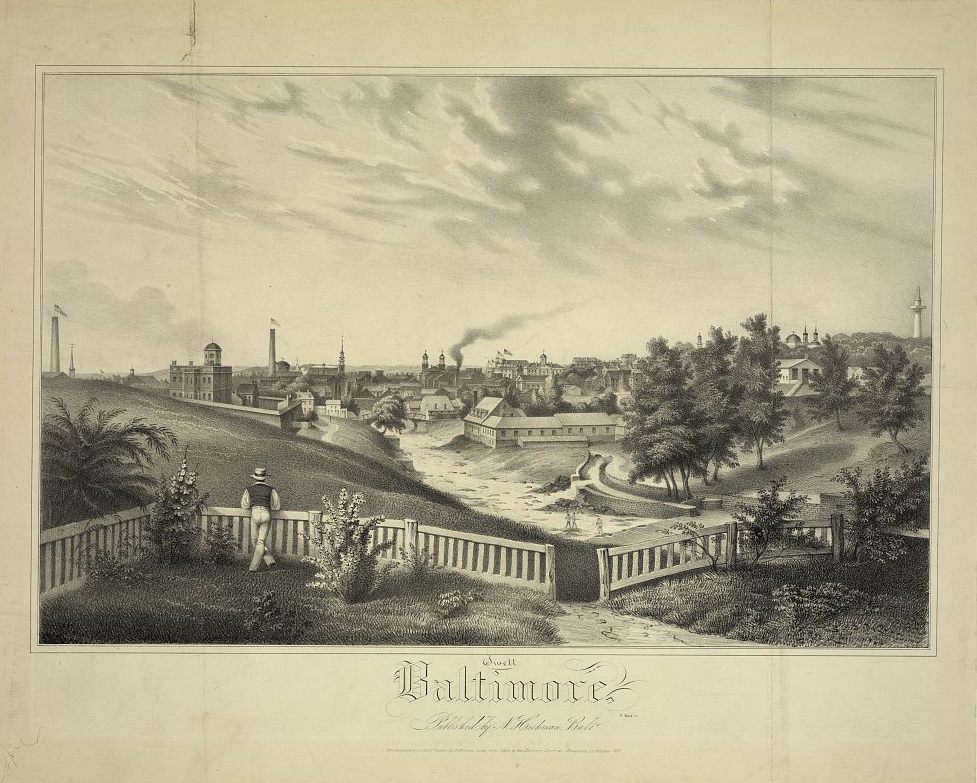

Cooping was rampant in Baltimore, but it seems to have happened nearly everywhere in the United States. T. H. Spencer, accused of cooping for the Democratic Party of the time, said that “Before I was a resident of Baltimore I was familiar with cooping; I was educated in the democratic school, and taught to coop before I was a voter.” He added that other major political groups cooped: “in the year following the Whigs commenced cooping, as they followed in electioneering what the democrats did.” The Indianapolis Sentinel wrote that “gangs of repeaters, thugs and perjurers” made Philadelphia’s “Republican stronghold to be the rottenest, most corrupt place in the country.”

A scene showing Baltimore in 1837, where cooping was rampant. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-pga-04182)

Witnesses of a fraudulent election in Boston, later said that the election “was carried out by violence and murder” and that politicians would bring gangs from New York, Delaware, Washington and Alexandria to help win elections. Senators from both the Democratic and Republican parties were outed during an investigation of a plan to use “repeaters.” Later, new African-Americans voters of the 1880s were often cooped until after election day, the threat of which was to keep them from voting on the Republican ticket, sometimes after Democrats already voted under African-American voters’ names.

New York City gangs, as dramatized in the film Gangs of New York, bullied people into voting multiple times for mayor; in real life, gang leader Mon Eastman said “I make half the big politicians,” publicly acknowledging the corruption of Tammany Hall. Even small elections, like that of Sacramento’s fire department, were controlled by election gangs.

The American Party (also known as the Know Nothing party) whose own heritage came from European colonizers, famously believed in passing anti-immigrant legislature using election cooping in the 1850s. They also used other tactics, including the “blood tub”, which included dragging a bucket of blood from a local butcher to the polls, grabbing Irish and German immigrant voters, and squeezing a sponge full of blood over their faces to discourage them from voting.

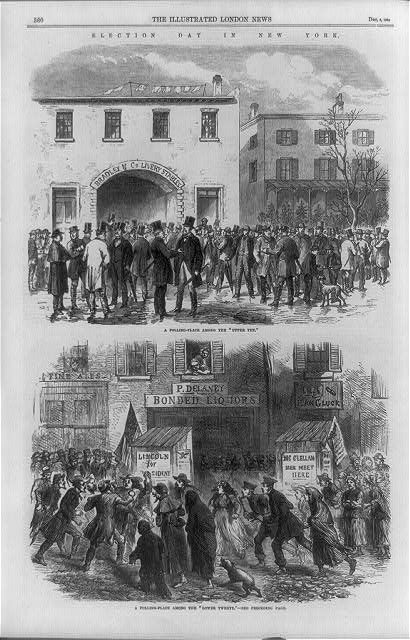

Two different scenes on election day in New York in 1864, in a wealthy and a poorer neighborhood. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-99844)

It’s uncertain whether all repeat voters were victims of cooping, or if some were merely bribed, though it was unlikely every victim would come forward, given that voting multiple times was illegal. Some cooping victims hardly remembered who they voted for, who captured them, or where they went. Sometimes they even crossed county or state lines. In Oregon, a news report from the small town of The Dalles announced, “It leaked out today that worthless characters are to be shipped from here to Portland to be used as “repeaters” in the primaries Thursday.”

Over time, corruption in politics was scrutinized more. New voting laws were put into place, and the secret ballot let voting be a private event that happened alone in a booth, away from prying eyes or potential threats. Sometimes police were sent to watch caucuses to ensure that no one would repeat their votes, though cooping-like instances survived into the 1920s in Chicago with Al Capone’s voting line raids.

Today there’s little evidence of the corruption of elections past, and paranoid laws that keep voters from the polls are finally beginning to wane. These days, at the very least, if American voters feel the need to drink through this election, it’ll be by their own choice.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook