Ellis Island’s Forgotten Final Act as a Cold War Detention Center

A group of immigrants wave goodbye as they are deported, 1952. (Photo: Library of Congress)

On November 17, 1950 famed Hungarian-born violinist Joseph Szigeti arrived in New York City to begin an American concert tour. Szigeti was no stranger to the United States, having already toured the U.S. over two dozen times. But within minutes of his arrival, immigration officials removed him from his ship and delivered the bad news—the U.S. Department of Justice had refused his admission into the United States. Officials quickly carted Szigeti to a detention site familiar to nearly all Americans—a 27.5 acre piece of land in Upper New York Bay known as Ellis Island.

“It makes me a prisoner,” the bewildered 58-year-old musician, a California resident for the previous nine years, told the New York Times, “What have I done?”

At the time, Szigeti’s case was far from exceptional. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Ellis Island became a de facto prison for an improbable mix of immigrants, visitors, displaced persons, political dissidents, and refugees from across the globe. Caught up in the sweeping paranoia of the Cold War, the majority of Ellis Island’s denizens were suspected communists, incarcerated at the immigration port while the United States undertook lengthy, and often secretive, reviews of evidence against them.

These immigrants and foreign nationals remained trapped on Ellis Island for months and even years. And much like Szigeti, many never knew the exact charges against them or the specific evidence the Immigration and Naturalization Service used to detain them. As Szigeti’s lawyer reported, they had no idea what was in the Department of Justice files, making it particularly difficult to craft a defense of their client. This pattern of restricted civil liberties was born in the World Wars, but found surprising staying power as the United States entered the 1950s and confronted new ideological demons.

A poster for Joseph Szigeti’s 1930 concert in Paris. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

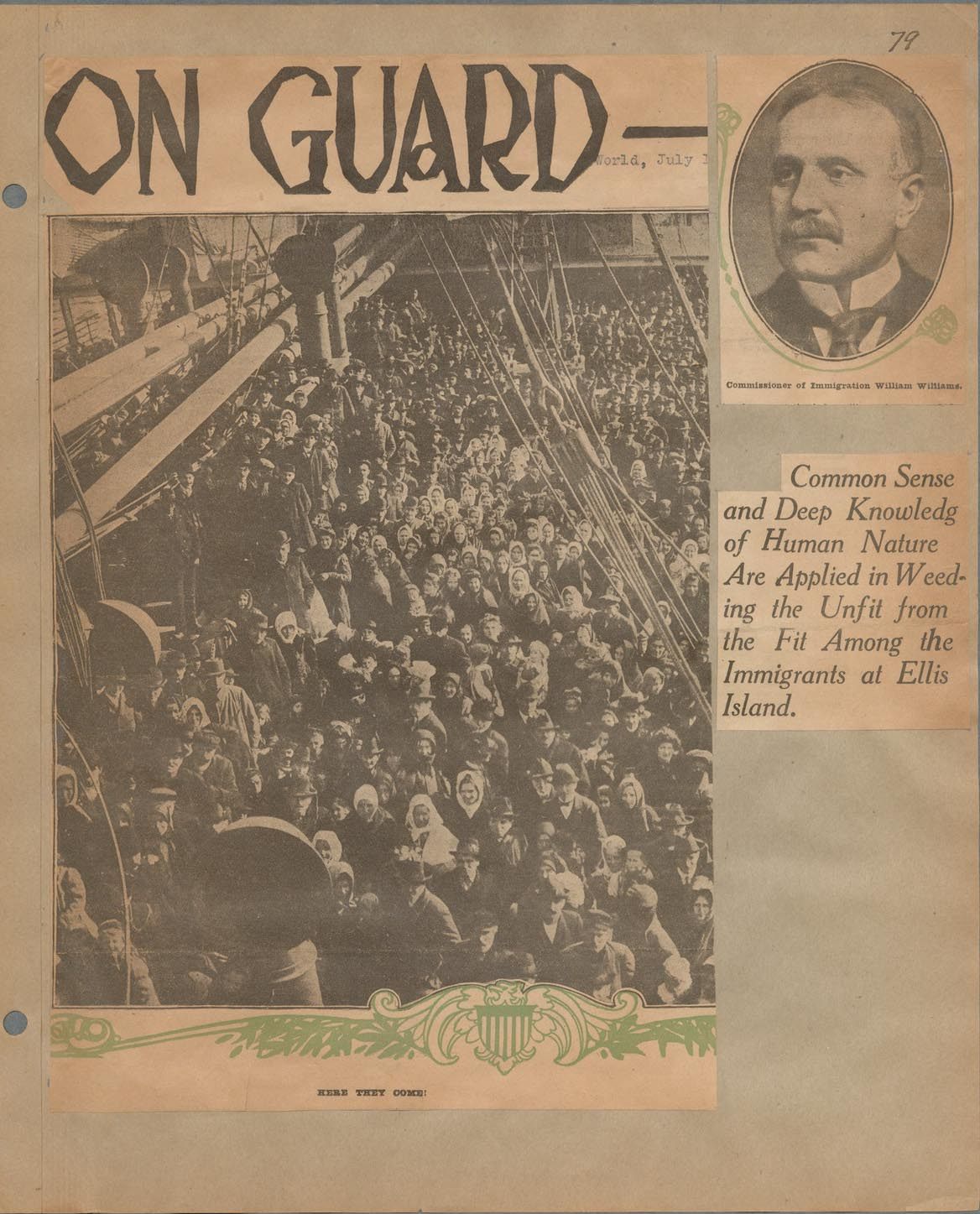

This, of course, runs contrary to the popular vision of Ellis Island. The site has occupied, and continues to occupy, a revered place in the national imagination—it’s estimated that around a third of the U.S. population today can trace family to the New York City port. The most common images of the site come from the early years of the 20th century, when immigration from Europe was relatively unrestricted, and immigrants from across the Atlantic poured into the United States with ease.

But this is far from the full story. In 2016, America continues to grapple with many of the same issues that plagued it at Ellis Island—what are the rights of those who come to the U.S.? What constitutes “acceptable risk” in admitting the foreign-born? What does due process look like for those jailed in the U.S. yet not charged with criminal acts?

Ellis Island is not a simple symbol of American opportunity—the proverbial golden door had a very tight lock.

‘You can see Miss Liberty from your window but she can’t see you’

Ellis Island did not become a detention center overnight. Even as the beacon of America’s open doors, the site was rarely without controversy in its 50-plus years of operation. But the image of it being a way station, not a holding cell, is factually accurate—prior to 1921. Before then, officials allowed nearly all European immigrants who arrived at Ellis Island to enter the United States; only one to two percent were excluded each year, usually on the basis of illness or their risk of becoming “a public charge” in America. For the vast majority of immigrants, Ellis Island was a quick pit stop on their journey to the U.S.

The role of Ellis Island changed in 1921, when Congress established national quotas capping how many immigrants could come from each country in the Western Hemisphere. Immigrants who came in excess of their nation’s quota (most commonly immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe) could be detained on Ellis Island until officials arranged for their return. It was then that the island began to transition from straightforward processing point to something murkier.

According to Ellis Island Commissioner I.F. Wilson in 1931, the changing immigration rules represented “a complete reversion.”

“Whereas previously it was regarded as the gateway to America, it is now the port of expulsion,” he wrote, “our Law Division and Deporting Division are the two most important at the Station.”

The Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. (Photo: Phil Dolby/flickr)

The World Wars posed a particular challenge for the island. If the United States sent a deportation steamship across the Atlantic during a war, there was a fair chance it could receive unwanted attention from a military submarine. As a result, maritime safety issues forced the United States to temporarily hit the brakes on trans-Atlantic removals at a time when paranoia about the “enemy alien” was higher than ever. Though the story of the Japanese internment has become increasingly well known, it’s perhaps less recognized that the U.S. also incarcerated significant numbers of visitors and residents from other countries that the United States was fighting. Ellis Island, with its large dining halls and good-enough dormitories, was prime internment real estate.

For instance, four days after Pearl Harbor, 413 German “enemy aliens” found themselves in detention at Ellis Island—many were accused of affiliation with the Nazi Party, and would stay there for the duration of the war. At the peak years of wartime internment, Ellis Island held between 1,600 and 1,800 people, primarily from Germany, Italy, and Japan.

By the end of World War II, memories of Ellis Island as a joyous port of entry were a hazy memory; the New York Times reported that, to the contrary, “the Island’s name had become a symbol for being unwanted by America.”

The Ties that Bind

With the war over, most Americans assumed that Ellis Island’s role as a detention center would come to an end. Ships could traverse the Atlantic once again, and most of the remaining detainees could be safely deported to Europe. But rather than a return to normalcy, paranoia about foreign influences and communist subversion triggered even more detentions.

In 1950, Congress passed the Internal Security Act, over the veto of a very unhappy President Truman. The law marked a new era in anti-communist hysteria, and made nearly every foreign-born person, both visitors and immigrants, a suspected subversive. Under the new policy, the United States would deny entry for any alien “who holds or has held membership or has been affiliated with any totalitarian or Communist organization,” formalizing a policy that had existed in practice since the end of the war. The director of Immigration Service informed the New York Times that it was “immaterial” how long ago or for what amount of time the alien was affiliated with such a political group—“A connection that was broken after even a single day is as binding as one that lasted for a period of years.”

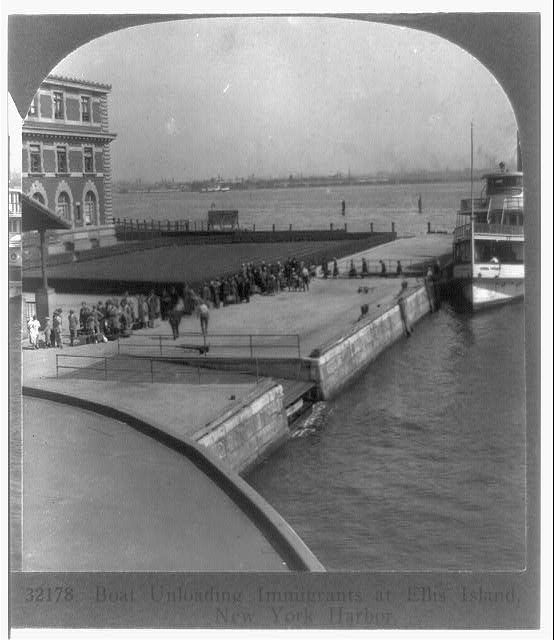

A photograph from the early 1900s showing immigrants who have passed and are waiting to be taken off Ellis Island. (Photo: The New York Public Library)

What this meant in practice was that entire steamships of immigrants coming from nations like Italy—where one would be hard pressed to find anyone without a fleeting “affiliation” to their nation’s totalitarian government—all now faced extended detentions at Ellis Island. An Italian opera singer named Fedora Barbiei was detained at Ellis Island after admitting that she attended a Fascist school as a child—effectively debarring any Italian who received an education during the years of the Fascist regime. Two weeks after the legislation passed, Ellis Island officials were holding nearly 1,000 foreign detainees, hailing from countries as disparate as Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Cuba, Germany, and Italy.

If the term “affiliation” seems a little vague, that’s because it was. Immigration officials had broad discretionary power in determining what constituted an “affiliation,” and immigrants had little recourse to protest their exclusions. Since the Supreme Court had long held that deportation was “not punishment for a crime,” those being detained and sent back across oceans had no right to legal representation or a trial by jury. Though immigration officials always had enormous amounts of power to make decisions about who would be let in, in earlier years those decisions were about who had enough money, who entered the country with a job, and who was visibly ill. Now the same officials were conducting extensive, invasive interrogations about foreigners’ political pasts, often with minimal training.

Friends in High Places

In you were unlucky enough to arouse the suspicion of immigration officials, it helped to have powerful friends on call. The musician Szigeti, for instance, as a well-known public figure, was able to get his papers expedited from Washington, D.C. and the backlash to his detention was almost immediate. Newspaper editorials called out “Ellis Island Horseplay” labeling the security protocol “ridiculous” and the ongoing detention of foreigners like Sziegti a “national embarrassment.” His detention was brief, and within six days of arriving on American shores he was conducting an orchestra in Pittsburgh. Most other detainees would not fare so well. The New York Times reported that immigration authorities “declined to say” why Szigeti was detained and “made no explanation concerning his release, either.”

In 1948, the U.S. government detained a Nobel Prize winning scientist at Ellis Island, who just so happened to be Marie Curie’s daughter. Irene Joilot-Curie was also, conveniently, a close friend of Albert Einstein. It was later revealed in the FBI’s 1,800 page file on Albert Einstein (the U.S. heavily suspected Einstein was a foreign intelligence agent) that he had personally telegrammed authorities to express dismay at Joilot-Curie’s detention, and encouraged other American scientists to do likewise. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Joilot-Curie was released in under 48 hours.

As a general rule, the less paperwork you brought to Ellis Island, the more trouble you were in—since the vast majority of people arriving in the post-war years were “displaced persons,” many of whom had been on the run from extreme violence and persecution. Proper paperwork was often a distant dream. The average detention at the island was about eight to ten days, but stories abounded of immigrants stuck in immigration purgatory for months and even years. In 1953, the Los Angeles Times reported on the story of Karl-Heinz Pfeiffer, a 17 year-old Polish teenager who fled his home country, and walked westward through the dead of night for several days until he reached West Germany. Once in Frankfurt, the teenager snuck onto the (heated, pressurized) cargo compartment of a Pan American plane bound for New York City. He arrived on Ellis Island without a scrap of paperwork or proof of identity.

A manuscript from the early 1900s about how Ellis Island’s approval process worked. (Photo: New York Public Library)

A year later, Pfeiffer was in exactly the same place—a dormitory on the island, while the U.S. tried to determine what to do next. The Times opined that there “was a time when a shrewd examiner, looking at him and hearing reports of his cheerfulness to work during his exile on Ellis Island might have thought; It’s a big country, let the country swallow him and he will serve her well.” But things were different in 1953. The Times assessed his chances of becoming an American in the midst of the Cold War were “roughly the chance of a snowball’s chance in August.” As immigration law became more punitive, officers had more discretion to exclude and deport, but less freedom to make exceptions. When in doubt, they erred on the side of exclusion.

Managing Ellis Island

The post-war years were a tough time to be in charge of Ellis Island. The question of whether Ellis Island was a prison created significant tension for immigration administrators trying to explain the site’s changing role to the public. “The people detained here are not criminals. That’s the first thing I teach my security officers,” Ellis Island Chief Phillip Forman told the Reading Eagle in 1951.

Representatives of the immigration service highlighted the relatively humane conditions in which the detainees were held, arguing that the site was more a “self-contained city” than the “concentration camp” its opponents labeled it. The island had some amenities: a chapel, a post office, laundry service, and a kindergarten and playroom for children. Single men stayed in “bachelor’s quarters” with six beds to a room, while families received rooms of their own with beds, drawers, and a chair. Reports proliferated of women attempting to make the dormitories more livable—hanging up lace curtains from their luggage or scrubbing the decades of grime off the rooms. A 1950 newspaper photograph showed a woman bent over an ironing board, with the caption “LIFE GOES ON: Detention in Ellis Island does not deter housewives from the family ironing.”

The detention pen at Ellis Island. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The highlight of a day in detention was the mail call, where detainees received letters, and the library call, where detainees were allowed to visit an on-site library operated by the Salvation Army. The library had more than 20,000 books, alongside newspapers and magazines in many languages—commissioners reported that the most popular selections were fiction and books about art. There was also a commissary selling candy, soda, cigarettes, stamps, and stationary from which immigrants could purchase additional goods.

But despite the distractions, it was hard to combat the suffocating monotony of weeks in detention. “When the weather is good, men and women tramp endlessly up and down the yard with the fixedness of people who don’t like to admit they’re not going anywhere,” wrote one journalist in 1950. Ellis Island’s yard had a sweeping view of the Manhattan skyline, which detainees would peer at through the high wire-mesh fence that surrounded the site. “Here was a subtle torture,” a writer for the New York Herald Tribune opined, “for inmates could divert themselves for days with this picture postcard view of the Promised Land while reflecting that this might be as close as they’d ever get.”

Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, 1927. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In an attempt to garner more favorable press coverage of the island, officials paraded journalists through the facilities on an annual basis. Reports came back mixed. In 1948, a journalist reported that German detainees had engulfed reporters attempting to plead their cases and declaring their “love for democracy.” Multiple news outlets reported that the detainees yelled to the reporters that the conditions and food had been temporarily improved to impress the media. Other times the press tours seemed to be veering into bribery—before a 1949 tour, all reporters were given a filet mignon lunch at the island’s cafeteria. When reporters inquired if this was the kind of food the detainees received, the Ellis Island Commissioner laughed at the absurdity of the question, responding, “There are only so many filets to a steer.” (Translation: No.)

Much like the second Red Scare itself, detention at Ellis Island had fierce critics and adamant defenders—those who claimed every detainee was a communist, and those who claimed few were, those who argued the conditions were sub-human, and those who argued the island was better than many Manhattan hotels. The reality was likely somewhere in the middle. One journalist who had been critical of the lengthy detentions and shaky legal precedents conceded that “(unarmed) guards, freedom of communication, second helpings at mealtime, a school for children, a hospital for the sick, a constant effort on the part of officials to make themselves approachable” all indicated that the United States “(was) not aping Hitler’s concentration camp methods.” Faint praise indeed.

‘America’s Own Concentration Camp’

Excluded aliens did not quietly accept their fate at Ellis Island. Resistance by immigrants took many forms, but one of the most dramatic (and enduring) means of protest was the hunger strike.

A 1948 hunger strike orchestrated by Gerhart Eisler, a man U.S. officials described as the “brains” of the Communist party in the United States, became a particularly lively media circus. Eisler, along with four other labor organizers detained on Ellis Island, refused to eat for nearly six days, arguing that as legal residents of the United States, they had a right to bail rather than detention while the government reviewed their deportation cases. For six days, they drank only water, as the media published a steady stream of articles speculating over whether they had a secret food supply. After nearly a week, the court relented and released four of the five men on $3,500 bail each.

Hunger strikes galvanized activists, triggered media attention, and in the case of Eisler and company, got them the legal results they wanted. “I can’t eat. I’m not concerned with food. I’m more concerned with freedom,” one protester crowed to reporters.

A postcard showing Ellis Island in 1930. (Photo; Library of Congress)

Other detainees tried to channel their idle time into more ambitious political projects. C.L.R. James, a prominent historian and social theorist from Trinidad, spent nearly six months on Ellis Island, where he worked for 12 hours a day on a critical literary analysis of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. James sent a copy of his manuscript to every member of Congress, hoping it would cement his credentials as an intellectual and forestall his deportation orders. He also included a request for $1 to put toward his legal defense fund. Unfortunately, most congressmen were confused as to why they were receiving a book about Moby Dick from a detained Caribbean immigrant. The United States deported James in 1953. (Perhaps James got the last laugh: his Melville tome was re-released in 2001, with the New York Times hailing it as a “170-page amalgam of brilliant critical analysis and desperate personal pleading…evidence of a major James revival now under way.”)

Though excluded foreigners had no right to a trial, many received one anyway thanks to the relentless work of immigrant advocacy organizations. Both the ACLU and the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born (ACPFB) organized legal and political campaigns that sought to bring immigrants’ cases to court, far away from the discretionary authority of the Ellis Island officers. They also worked to provoke a sense of public outrage about the perceived injustices at the NYC port. These organizations frequently used the language of civil liberties and suggested that anti-communist crusaders were dismantling the Bill of Rights. They also relied heavily on the “slippery slope” argument—first the government arbitrarily detains immigrants, but next they’ll arbitrarily detain you, the citizen.

The organizations insisted that unchecked federal power and suppression of free speech was a threat to all Americans. Many people bought into this idea—they arranged letter writing campaigns, sponsored fancy dinners with formerly detained speakers, and even produced plays about the plight of detained foreigners. Sometimes these organizations argued that the people on Ellis Island were being falsely accused of communist affiliation, but even more frequently the advocates argued that it didn’t matter if these people were communists—political ideology was irrelevant to legal rights. In the context of the Cold War, this was a bold, progressive, and extremely contentious argument.

German immigrants wait on Ellis Island. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R17676 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Immigrant advocates paired the language of rights with inflammatory accusations of injustice. One of their most devastating claims was that Ellis Island was “America’s concentration camp.” Unsurprisingly, the term became a particularly blistering critique in the wake of World War II, and the ACPFB used the comparison in almost every publication. Activists also deployed comparisons to the Nazis to highlight the discriminatory nature of U.S. immigration law, which explicitly favored immigrants from Northern and Western Europe. “We fought a war to destroy the Nazi myth of racial superiority,” one ACPFB pamphlet proclaimed, “But the ghost of that racial myth still lives—in the immigration laws of the United States of America.”

Even more concerning in the midst of the Cold War was that America’s allies and enemies both had some big questions about what was going on at the NYC port. Why were such large numbers of their countrymen being imprisoned with no trial and no formal charges? “The wholesale detention of Italians on Ellis Island,” wrote one foreign correspondent, “is interpreted as an insult to the Italian people and an affront to the national pride.” Italian newspapers flashed headlines like “Absurdities of an American Law” and “Spy Mania of America,” while embassies from Sweden to France petitioned the U.S. for the release of their citizens.

Closing Ellis Island and the End of Detention

Ellis Island shut its doors in 1954, after processing over 20 million immigrants. There were many reasons for the island’s eventual decline—fewer and fewer immigrants were moving through the port and the island’s buildings were in total disrepair. But on top of this, public opinion about the island had become more critical than ever. When a 1953 Supreme Court case determined that if deportation was not an option, an immigrant could be detained on Ellis Island forever, many Americans saw it as the final straw.

In the wake of the closure, government officials went on the record saying that a regrettable period of immigration law enforcement was over. The 1952 McCarran-Walter Act made detention “the exception, not the rule” and created a new policy where most deportees would be released under parole rather than detained. Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark clarified that detention of aliens would be “employed only as to security risks or those likely to abscond” and added, “certainly this policy reflects the humane qualities of an enlightened civilization.”

A troopship convoy out of Brooklyn in 1942. At the peak of WW2-internment, Ellis Island held between 1200 and 1800 people. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But in November 1954, mere weeks after the government shuttered Ellis Island, the New York Times reported that the remaining detainees had been moved off of the island and into local jails—a far cry from the “new policy of administering the immigration laws humanely” that the INS had trumpeted. The case of whether people who broke immigration law could be held among “common criminals” generated an outpouring of public concern. One letter to the Times held that “the conditions at Ellis Island, which was virtually a prison, were bad enough; but to send incoming visitors to our shores…to jails is an insult of the most serious kind.” Capitalizing on Cold War tensions, the writer speculated, “What an uproar would take place if Americans arriving in the U.S.S.R. were to be accorded similar treatment.”

Yet again, it was the intervention of a famous person that got results. Pearl Buck, author of The Good Earth, wrote a letter to the media denouncing the jailing policy and triggering multiple congressmen to launch investigations into the prison conditions. Within weeks the Sheriff of Westchester demanded that the INS halt the practice of placing foreign detainees in his county’s prison facilities. The remaining detainees were moved to an office building in Lower Manhattan. Despite their hopes to the contrary, the closure of Ellis Island was not a silver bullet for immigrant advocates seeking an end to detention.

So what would become of the island? Its role as a national heritage site was far from predestined. In the years after its closure, the federal government fielded bids to buy the island. The largest came from a New York builder, Sol G. Atlas, who planned to convert the site into a $55 million luxury resort called Pleasure Island, a “Miami Beach of the North.” As the developer envisioned it, the island would feature a 600-room hotel, swimming pools, a drive-in movie theatre, and a marina—plus, as homage to the island’s history, a Museum of New Americans and a language school. City and state officials also seriously considered a plan to turn the site into a hospital for narcotics addicts, before deciding it might look questionable to isolate addicts on an island.

Awaiting deportation, 1920. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Ellis Island’s fate hung in the balance until 1965, when President Johnson designated the station a part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. That same year, Johnson signed a law eliminating immigration quotas and marking a significant liberalization of U.S. immigration law.

Today, Ellis Island’s role as a site of mass exclusion and deportation is largely overlooked. Admittedly, the number of people passing through dropped over the years. At its peak, Ellis Island was examining and admitting as many as 5,000 immigrants a day; this number had plummeted by the Second World War. But the emphasis on the island’s early years is also a political decision. A country that has long embraced the self-image of a “nation of immigrants” relied on Ellis Island as a symbol of all that is good about our immigrant past. As the Cold War raged on through the 1960s, Ellis Island became almost hallowed ground, with the immigrant as a heroic liberty-seeker, finding freedom and opportunity beneath the Statue of Liberty. The flip side, a complex tale of hunger strikes, political interrogations, and fierce debates over civil liberties was not necessarily the narrative visitors to New York City sought.

Meanwhile, detention has reemerged as a critical tool of 21st century immigration authorities. The U.S. government currently detains over 400,000 people a year who are awaiting deportation hearings. These immigrants and asylum seekers sit in detention centers, county jails, and federal prisons throughout the country for weeks to years, caught in an all-too-familiar legal limbo. If we can forget what happened at the most famous immigration site in American history, Ellis Island, it’s no surprise that we hear so little about the conditions in our detention centers today.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook