Why England Was A Year Behind Belgium, Spain and Italy for 170 Years

William Hogarth’s satirical painting, “An Election Entertainment” (1755), includes the words “Give us back our eleven days!” (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 1584 a violent, angry crowd ransacked the city of Augsburg, Germany. Citizens broke through thick windows and shot their guns into the street. They were marching to City Hall to make it clear that they would not take the authorities’ new plans sitting down. They were in the midst of the Kalenderstriet, or “calendar conflict.” It was a response to the proposed change from the Julian calendar, which had been used for over a thousand years, to the Gregorian calendar, which would fully skip 10 days.

The people of Augsburg weren’t just upset that their calendar was being changed, which would skip birthdays and ruin weekends. Germany was a largely Protestant territory with a history of war between Catholic and Protestant groups. Augsburg, at peace since 1555, was home to both Catholics and Protestants. But the Lutherans in charge there viewed the Catholic-supported Gregorian calendar as an abomination and threatening force. They were particularly suspicious of the Pope who implemented the new dating system in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII.

The marketplace in Ausburg, Germany in 1550. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In The Reformation in Germany, C. Scott Dixon explains that not only was this a fight to control Augsburg’s harvest, holiday and trade schedules, but that the religious conflict was so tense that Lutheran astronomers “spoke of the pope as the Devil and the calendar as a diabolical plot intended to reintroduce papal sovereignty.” Catholic authorities, meanwhile, thought of the city as a heretic-ridden and deserving of any act to “root them out.”

A riot was the only way to go, or so thought some 16th century Augsburgers. And this was the only beginning of a few centuries’ worth of confusion, anger, and complication in regards to calendars.

The reasons for the calendar change, in an astronomical sense, were less sinister than the people of Augsburg assumed; Aloysius Lilius, the astronomer who proposed the project, was just trying to improve the dating system begun by Julius Caesar. Before Caesar implemented the Julian calendar in 44 BC, date-keeping in was an inconsistent mess, mostly because Roman politicians had the freedom to change the length of a year to kick their rivals out of government.

While the Julian calendar gave us 365-day years divided into 12 months, it didn’t account for a stray 10 minutes and 48 seconds—just enough to make days fall behind over time. By 1582, when the Pope first introduced the Gregorian calendar, Europe was 10 days behind. This was a problem for the Church because it meant Easter was not landing on the Sunday after the Spring equinox, like it was supposed to. The new calendar fixed the issue.

Pope Gregory XIII, the namesake for the Gregorian calendar. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The importance of holidays, fasts and feast days explained the Church’s interest in keeping the calendar “correct,” but the rift between religious groups in Europe meant that the change was haphazard around the continent, sometimes even centuries apart. Catholic-majority nations like France adopted the changes right away, but Orthodox Christian and Protestant-majority countries held off.

But the longer a country waited to shift to the Gregorian calendar, the more days needed to be removed; in 1752, England and its colonies went to sleep on September 2 and rose on September 13, as per the Calendar Act of 1750. Russia didn’t change calendars until February 14, 1918 and skipped a whole 13 days, meaning their October Revolution of 1917 actually happened, by today’s dating system, in November.

Wait, so Russia’s October Revolution of 1917 actually happened in November? (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The year’s length changed in many places during the transition, too. While the Julian calendar initially started off with January as the first month in the year, religious holidays took precedence as year-openers after the Roman Empire fell. For centuries, England had celebrated New Year’s on Lady Day (or Feast of the Annunciation), on March 25, but 1752 jarringly began anew in January, making 1751 the shortest year England ever recorded, with only 282 days.

That year, the English Whigs and Tories fought so much about the calendar reform that William Hogarth later made a satirical painting called “An Election Entertainment” that showed riots and the words “Give us back our eleven days!”, beginning rumors that 18th century England might go the way of 16th century Germany, and riot about the calendar changes.

By this time, however, keeping track of the date had become bewilderingly complicated all over Europe. After 1752, Europeans started using a dual dating system to make up for the discrepancies between countries. For example, instead of writing George Washington’s birthday using the Julian calendar date of Feb 11, 1731, recorders interested in keeping accurate records would write Feb 11, 1731/1732, since the new year had been moved to January (which changed the year he could record he was born).

A Roman calendar from before the Julian reform ca. 60 BC. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

If a date moved to a different month, it would be written similarly (December/January would indicate old and new). Alternatively, next to a date, the terms “Old Style” or “New Style” would be indicated. This dating system meant that people generally kept track of two birthdays and marriage dates, and indicated Old Style vs New Style on obituaries.

Much of the Spanish Netherlands (comprised of large swathes of modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg, and northern parts of France and Germany), had to technically skip Christmas altogether in 1582, as the region unfortunately waited until December 21 to switch over to the new calendar, and thus lost 11 days.

Greece was the last country in Europe to make the switch, in March of 1924, with much dissent from Greece’s Old Calendarists, who still use the Julian Calendar to this day. This move once again interfered with Christmas celebrations; the political year of 1923 occurred sans Christmas, which was subsequently celebrated twice in 1924.

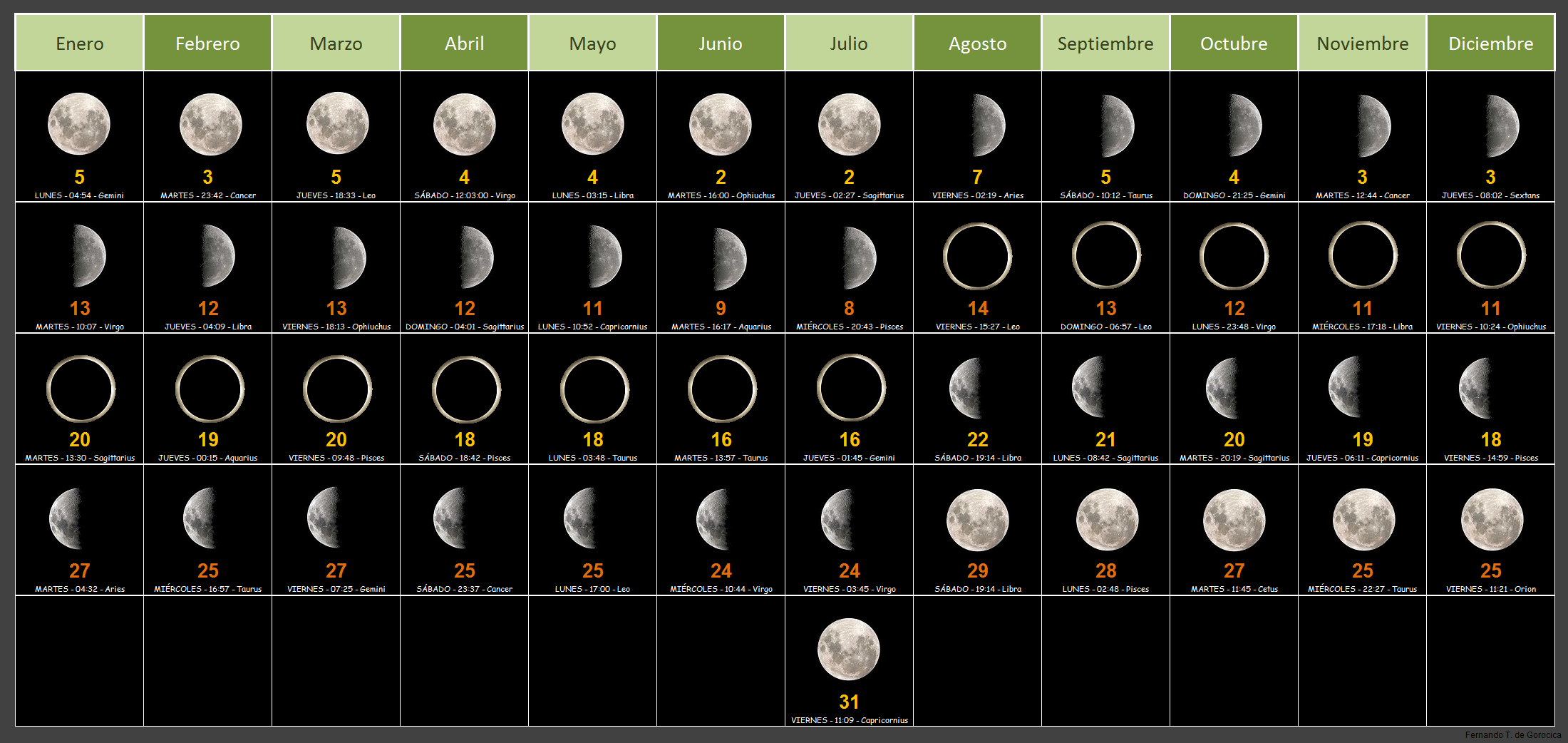

You can also track time with lunar calendars like this one. (Photo: Fernando de Gorocica/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Of course, the Gregorian calendar isn’t the only way to accurately track dates; it just matches astronomical events with holidays that were important to some Europeans at its creation. When other cultures began adopting the calendar later on, there was little problem with simply keeping a separate, local calendar with their own holidays.

These days, many cultures have their own dating systems (the Thai, Iranian and Jewish calendars among them) and reserve the Gregorian calendar for global use. China, which has used the Gregorian calendar in different forms since 1912, has two traditional local calendars: the lunar, which follows the cycles of the moon, and the solar, which is similar to the Gregorian calendar except for having leap-months; every few years there are around 385 days.The Ge’ez calendar of Ethiopia also uses leap months, but has a different calculation for Jesus’ birth from the Gregorian version —which currently makes it 2008 in Ethiopia, not 2016.

And make no mistake: the Gregorian calendar, like any calendar humans are likely to devise, is far from perfect. With the earth’s irregular rotation making accuracy difficult, physicists occasionally try to correct our timekeeping by adding leap seconds to certain years. It’s estimated that by 4490 or so, if no further calendars are made, those of us on the Gregorian system will be a full day ahead. Hopefully, next time the dates are moved around, it’ll be a bit easier.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook