Will These Glass Eels Beat the Odds and Survive to Spawn?

Critically endangered, and a much-sought delicacy, the animals are imperiled at every turn.

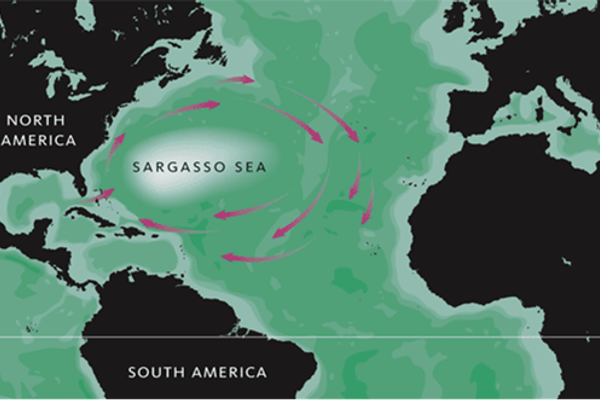

Spare a thought for the humble European eel. These ancient fish begin as eggs somewhere in the western Atlantic Ocean’s Sargasso Sea—the exact location of the spawning grounds of Anguilla anguilla remains a mystery. As larvae, they drift toward Europe, more than 3,000 miles away. Along the journey, which can last for two years, they develop into glass eels, as shown in the photo above: near-translucent creatures, a few inches long at most.

“As a glass eel, you’re a tiny animal, you’re one-third of a gram,” says biologist Willem Dekker, director of science for Europe’s Sustainable Eel Group. “If you have to swim all the way from the Far Sargasso to here, and then move into the rivers, you don’t have the energy for that. So, you use the current.”

Some researchers have estimated that only one out of every 500 glass eels survives to reach Europe. Still largely at the mercy of the tides and currents, they would traditionally head to river estuaries, mostly on the west coast of France but also along the coasts of the Mediterranean, and the North and Baltic Seas, even as far east as Finland and Russia. The rivers would become their homes for several years as the young eels mature, losing their glassy appearance and growing to two or three feet in length. Then they’d set off on a journey back to where they were spawned to start the cycle again. At least, that was the plan.

Humans, as we are wont to do, meddle in their natural life cycle, sometimes intentionally and sometimes not. Eels are considered a delicacy across much of the world, and each year poachers net millions of glass eels as they congregate at river estuaries, waiting for an incoming tide. Most of the illegal catch is shipped to farming operations in Asia: The illegal European eel trade is worth billions each year. For those that evade the poachers’ nets, flood control gates and other coastal infrastructure can block their progress upriver. Many of the eels that do make it into river systems are killed by hydroelectric turbines or thwarted by dams and other artificial barriers.

To save the European eel, fisheries and other groups work, legally, to catch glass eels on the coasts and restock rivers where native populations have fallen by more than 90 percent since the mid-20th century. Once caught, the glass eels are kept in holding tanks before being flown to their next destination. Each spring, particularly in Germany, young eels are released en masse into local rivers. Despite being listed by the IUCN as critically endangered, many, if not most, of the eels released will also end up on dinner plates, legally and otherwise.

Dekker has researched the history of European eel restocking, a saga marked by geopolitical squabbling and greed ever since a French nobleman, in the mid-19th century, began transporting glass eels by stagecoach to his inland estate. Although Dekker and his colleagues were able to achieve some protections for the animals in recent decades, he worries about their long-term prospects. “In 2010, the total restocking, all over Europe, was less than in the earliest years, via stagecoach,” he says. “It has increased since then, but we are not yet up to historical levels. There are not enough glass eels left.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook