Europe’s First Pornographic Blockbuster Was Made in the Vatican

Copies of the 16 explicit paintings were turned into a booklet that circulated throughout the continent.

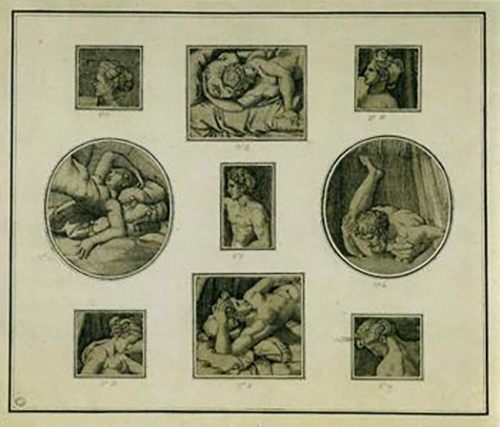

A section from a late 18th re-reaction of the original I Modi. (Photo: Public Domain)

Any pilgrims visiting Vatican City will spend some time in the Raphael Rooms. Decorated with iconic frescoes by Raphael and the artists of his workshop, these reception rooms in the Palace of the Vatican have left generations of tourists awestruck. They may also have inspired awe in the less high-minded.

According to legend, these Vatican showrooms, the apartments of the popes, once contained the now-lost artwork for the western world’s first pornographic blockbuster. (Note: explicit imagery accompanies this story.)

The Sala di Costantino is the largest of the rooms. It now depicts scenes from the life of Constantine, the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. Some art historians believe that other, more salacious sketches once adorned the walls. If those were still around, this room would be considerably more famous.

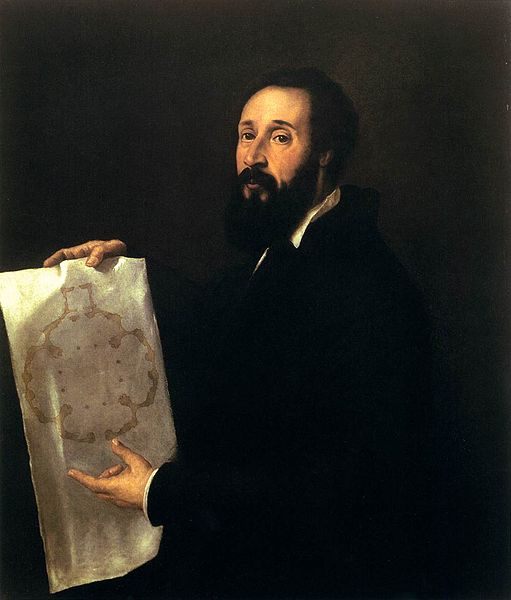

Titian’s portrait of painted Giulio Romano. (Photo: Public Domain)

Though it is one of the Raphael Rooms, Raphael was dead by the time work began on it. At least some of the work was left in the capable hands of Raphael’s pupil, Giulio Romano. Soon much of Italy was buzzing over exactly what those hands were capable of doing. Romano designed palazzos and decorated the apartments of cardinals, but he gained infamy as an artist who drew a series of 16 explicit paintings of lovers in different sexual positions, or “postures.”

According to Lynne Lawner, an art historian who focuses on Renaissance Italy, “In 1523 Giulio began the decoration of the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican. It is said that in a moment of anger at Clement VII for a tardy payment, Giulio drew the sixteen postures on the walls of that unlikely place.”

A reproduction of Satyr et Nymphe, one of the Sixteen Postures. (Photo: Public Domain)

This is not quite as insane as it sounds. Sex, art, and the Catholic church spent the 16th century as closely entwined as the lovers in Romano’s paintings. Rumor has it that Raphael was to be made a cardinal by Pope Leo X, but that he died of a fever caused by a night of sexual excess with his young mistress before the Pope could bring these plans to fruition. Records show that houses owned by the church or its officials were often occupied by young women with no last names, most likely the mistresses of church officials, kept quietly and anonymously near their lovers.

Even erotic art on the walls of the Vatican was not unprecedented. In 1516, a certain Cardinal Bibbiena earned himself a place in church history by commissioning Raphael himself to decorate a bathroom with naked nymphs bathing while anatomically correct satyrs spied on them.

Subsequent godly tenants whitewashed the bathroom, but art eventually won out over religion and Raphael’s paintings were uncovered and preserved—though to this day not made available to the general public. (Some art historians believe that Romano was actually commissioned to paint the sixteen erotic postures for Bibbiena, not Pope Clement VII, and that they depict 16 famous Roman courtesans–a sort of 16th century pin-up calendar.)

Raphael’s portrait of Cardinal Bibbiena. (Photo: Public Domain)

A cardinal’s bathroom is a private place. The erotic frescoes on the walls of the Sala di Costantino–whether commissioned or drawn out of spite–would have been kept equally private, no matter who trooped through the other Raphael rooms. Perhaps no one would ever have heard of Romano’s paintings if it weren’t for the efforts of another artist. Marcantonio Raimondi was a talented copyist, engraver, and print maker who made his reputation copying and printing Raphael’s works. He modified that reputation by copying Romano’s erotic paintings.

“The Sixteen Postures,” as they came to be known, circulated around Rome. If the church had not been involved before, it stepped in now—to its own great cost. Pope Clement VII tossed Raimondi in jail, but the copyist had powerful friends, and they petitioned the church on his behalf.

Bacchus and Ariadne. (Photo: Public Domain)

Among those appealing for Raimondi’s release was Pietro Aretino, a poet, satirist, and utterly fearless human being. The church’s reaction had piqued his curiosity. As he wrote to a friend later in his life, “After I arranged for Pope Clement to release Raimondi … I desired to see those pictures which has caused the [Vatican] to cry out that their creators should be crucified.”

Inspired by the explicit engravings, Aretino decided to add his own contribution. For each image, he composed a sonnet gleefully describing the scene. His words and Raimondi’s images were combined in a booklet that welcomed readers with Aretino’s introduction, “Come view this you who like to fuck, without being disturbed in that sweet enterprise.”

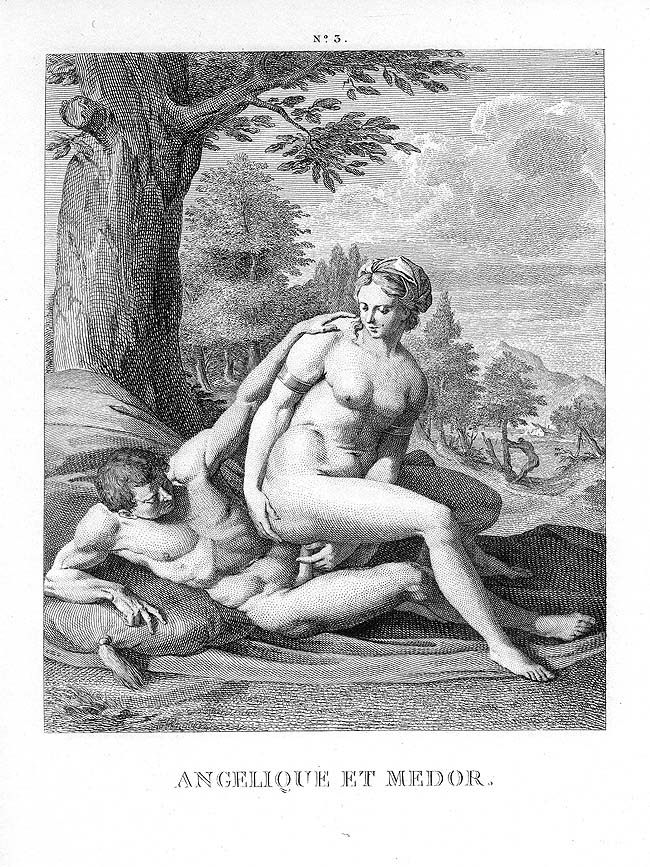

Angelique et Medor. (Photo: Public Domain)

The booklet had many names. I Modi or “The Fashion,” is the most popular. It’s also known as Aretino’s Postures, The Sixteen Pleasures, and De Omnibus Veneris Schematibus in Latin. Whatever it was called, people loved it. With the help of the printing press, the triumvirate (or trinity) of Romano, Raimondi, and Aretino had created the first printed porn blockbuster. Their work was first widely disseminated, then widely pirated, and finally widely imitated.

People all over Europe paid for the scandalous little book, but I Modi did more than just make money. It was one of those rare works of pornography that jumped from niche to popular culture. Like Fifty Shades of Grey or Deep Throat, it became something which could be discussed, if only as a joke, in polite society. Some believe that Shakespeare snuck a reference to I Modi into A Winter’s Tale, when he talks about “that rare Italian master, Julio Romano.” There was even a 16th century Italian phrasebook aimed at English tourists that allowed them to ask for the “works of Aretino” at Italian booksellers, according to Eric Berkowitz, who hunted down a copy for his book, Sex and Punishment: 4000 Years of Judging Desire.

Illegally-printed copies of I Modi remained popular for over a hundred years. There’s no way to know how many were printed. Sadly, there will be no modern-day revival of the work. Churches and governments hunted down and destroyed the copies as enthusiastically as people bought them. (This, ironically, might have been what kept the book in print for so long.) Only the sonnets survive intact.

Fragments of the I Modi or The Sixteen Pleasures as found in the British Museum (Photo: Public Domain)

Except for a few fragments in the British Museum, carefully cropped to remove any genitalia, the original images are gone. If the original paintings were the obscene work of an enraged artist, it’s not surprising they were destroyed. If they were commissioned, it’s also likely they were quietly eliminated. The church that whitewashed the work of Raphael, and painted draperies over Michelangelo’s male nudes in the Sistine Chapel wasn’t going to carefully preserve pictures of people having sex. The closest we can get to the erotic works of Giulio Romano are 18th century recreations of the 16 original engravings.

To pay tribute to the literary blockbuster he inspired, perhaps it’s best to go to Vatican City and head to the Sala di Costantino, with its scenes from the life of the Roman emperor who converted to Christianity and took much of the western world with him. Maybe behind the scene of Constantine’s vision of the cross, or his baptism, you might see the faint lines of a very different kind of painting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook