Exploring the Strange Pleasures of Cockaigne, a Medieval Peasant’s Dream World

The birds fly right into your mouth, and there isn’t animal poop everywhere!

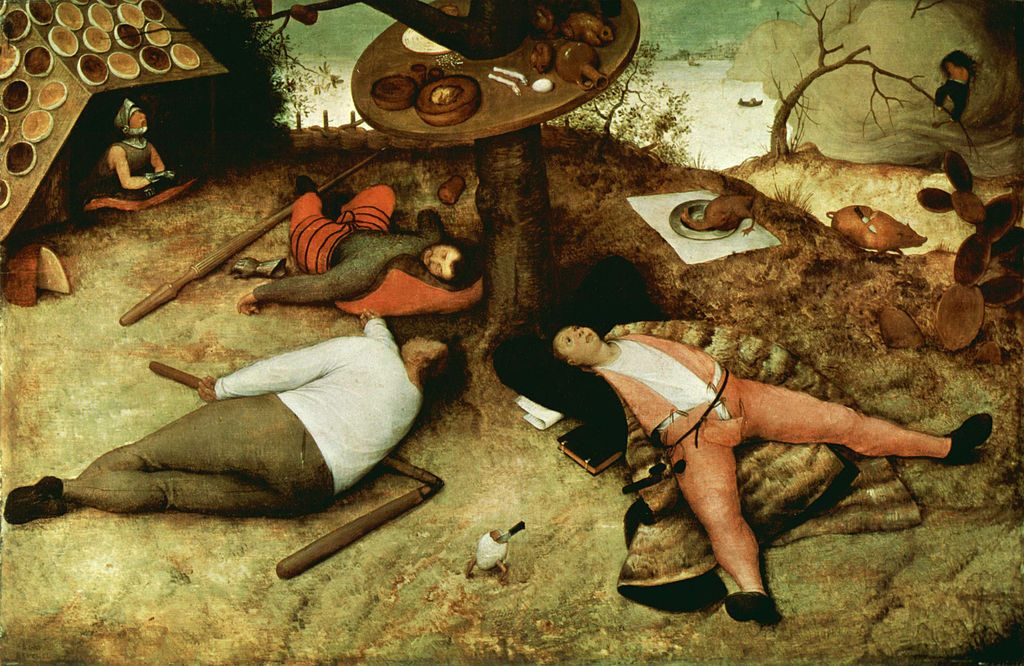

A 16th-century vision of Cockaigne as a land of shameful laziness and sloth. (Photo: Pieter Bruegel/Public Domain)

The dream of the common person’s utopia was more than a little bit different during medieval times. Whereas today we have visions of lands o’ plenty like a huge mountain made of rock candy, the common peasant living in the muck and the mire of medieval Europe had a whimsical, satirical dream land known as Cockaigne.

While there have been many different versions of Cockaigne appearing in literature throughout the ages, in general, the Land of Cockaigne was a medieval dream world where the regular order things was flipped on its head. In Cockaigne, the poor would be rich, food and sex were freely available, and sloth was treasured and respected above all else. It was often portrayed as the perfect daydream of the common peasant, a place where the drudgery and struggle of medieval life was nowhere to be seen. However, even though it was depicted as a serf’s perfect world, it’s unclear how aware of the concept of Cockaigne the average person would have been.

This literal land of milk and honey made its mark in the popular imagination thanks to countless poems and writings that began to appear all across medieval Europe from the 1300s onward. “It’s very hard to say how well common people would have known of Cockaigne,” says Karma Lochrie, author of the book, Nowhere in the Middle Ages, which looks at the medieval origins of utopian thought. “We know that visions of Cockaigne existed in all major European languages in the Middle Ages and beyond, but these visions would have only been accessible to elite readers who could read.”

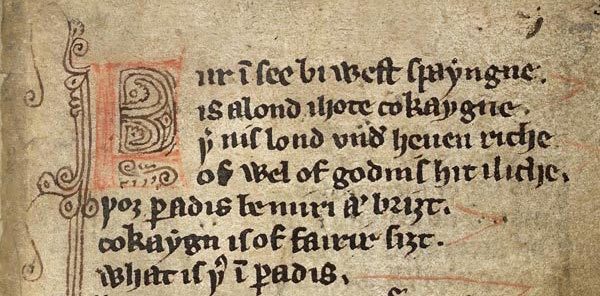

Nonetheless, with the spread of the printing press, tales and poems of Cockaigne became widespread enough that they would eventually reach a wider audience. As Lochrie says, while there are a great number of versions of Cockaigne, the most widely known account is a poem from around 1350 called The Land of Cockaygne. Contained in what is thought to have been a friar’s notebook, the poem details many of the barely imaginable wonders that Cockaigne had to offer, and gives us an unforgettable look into both the nature of the satire and the aspirations of people of the time.

The opening lines of The Land of Cockaygne. (Photo: Wessex Parallel Web Texts/Public Domain)

In the poem, Cockaigne is said to lie somewhere west of Spain, but in reality the promised land never had any concrete location on the map. “[L]ike Thomas More’s Utopia in 1516, one of the recurring features of Cockaigne is that we don’t know where it’s located,” says Lochrie. “It’s somewhere and nowhere, in effect.” But although Cockaigne doesn’t have a concrete location, the authors of the poem knew how to get there. As Lochrie pointed out, the final lines of the poem say that in order to reach Cockaigne, one must bury oneself up to their chin in pig shit, as a sort of backwards version of a purifying ritual. Yeesh.

But once a person reaches Cockaigne, what would they find there exactly? According to the poem, some very strange and very domestic pleasures. After first describing the traditional Christian paradise as boring utopia with nothing but fruit, saints, and no alcohol, the poem presents Cockaigne as the ultimate bacchanal, free of the unpleasantries of medieval life. There are no horses, pigs, or other domestic animals, not because they are especially ostracized, but because without them, there is no dung to shovel. Animals that could pose a threat or nuisance to a medieval peasant, like a snake or a fox, are nowhere to be seen. There is no night, no storms, and no one dies. The rivers flow with oil, milk, honey, and wine, and one line in the poem even says that the only use for water is to bathe. Water as beverage simply isn’t decadent enough for Cockaigne.

This guy could use a trip to Cockaigne. (Photo: The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry/Public Domain)

In the latter half of the poem the focus shifts from the wider world to a satirical abbey and its jolly monks, which Lochrie sees as a sign that maybe Cockaigne, or at least the concept of it, wasn’t as egalitarian as it seemed. “The fact that the English poem focuses so extensively on the monastery probably suggests it was not a paradise for the common folk, despite its claims that pleasure and culinary delights are available to all,” she says. But still, the antics of the monks are typical of a Cockaigne story.

At their Cockaigne monastery, the monks spend their days flying around until being called to the ground when the abbot spanks a maiden on her bare behind. Their only concern is being frivolous and lazy, when not casually bedding the nuns from a nearby convent. Fully cooked larks fly right into their mouths, and a series of springs that flow over precious jewels pour forth wine and medicine. It is singularly strange, but one can see how someone living in medieval Europe would be focused on such things.

While Cockaigne is not talked about much these days, its spirit lives on in songs like the hobo classic, “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” and even things like Charlie and The Chocolate Factory, although it has morphed away from much of the cultural commentary of the medieval concept. “It’s interesting that Cockaigne becomes a kind of children’s story in contemporary culture, both in Dahl’s story and in the Burl Ives version of the “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” says Lochrie. “Cockaigne, in its early versions and more recently, often includes satire as much as it does a vision of a kind of paradise.”

Still, there is something undeniably romantic about the land of Cockaigne, and its descendants even today. It might not be a real utopia, but sure is nice to dream about.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook