Why Do Fantasy Novels Have So Much Food?

Writers since Tolkien have conjured magical feasts for readers.

As a pre-teen, I devoured fantasy book after fantasy book. One day, I was stopped short by a food description. In Diana Wynne Jones’s A Tale of Time City, the era-hopping protagonists eat a treat called butter-pie. It’s yellow ice cream on a stick, ice-cold on the outside and molten on the inside, and described as “buttery and creamy … with just a hint of toffee, and twenty other even better tastes.” Butter-pie has never existed, except in the pages of Jones’s book and in the imaginations of readers. But it sounded delicious.

In those days, the internet was fairly new, so I couldn’t dig up the dozens of recipes that fans of Jones’s work have developed. But even as I moved from children’s fantasy novels to those meant for adults, I noticed that authors consistently incorporated lavish descriptions of food. It piqued both my appetite and my interest: Why do fantasy writers write so much about food?

As I doggedly read through the fantasy canon, I realized that the marvelous butter-pie was an outlier. Instead, heroes and heroines often ate familiar fare, even as they cast spells and rode dragons. For pages and pages, lucky characters feast on cakes and ale. Other characters only get stew, which is oddly omnipresent. In her satirical travel guide to fantasy literature, The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, Jones jokes that stew “is the staple food in Fantasyland, so be warned. You may shortly be longing for omelette, steak, or baked beans, but none of these will be forthcoming.”

Food in fantasy dates back to early myths and legends, which are full of symbolic, often menacing fare. The Greek goddess Persephone ate six pomegranate seeds in the underworld, consigning her to spend six months of the year with Hades, the god of death. European tales and poems abound with mystical fairies or elves using food to lure humans. In the poem “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” written in 1819 by Romantic poet John Keats, a knight falls in love with a fairy girl, who feeds him “roots of relish sweet, And honey wild, and manna-dew.” But one day, the knight wakes up to find himself abandoned and half-mad for what he lost. In 1859, poet Christina Rossetti wrote “Goblin Market,” about eerie, otherworldly creatures that sell fruit that, once tasted, drive people crazy for more.

The trope of dangerous fairy food still exists in modern fantasy, says Dr. Robert Maslen. Maslen is a senior lecturer at the University of Glasgow, where he founded one of the world’s first master’s degrees in fantasy literature. He gives two modern examples: the film Pan’s Labyrinth and Ellen Kushner’s novel Thomas the Rhymer. When food comes with consequences, it’s a sign that “we’re in a world where the rules are very different.”

The father of modern fantasy writing, J.R.R. Tolkien, was shaped by this tradition. As a child, he read the Andrew Lang fairy books, which reached 12 volumes and were organized by color, from Red to Blue and Pink to Brown.

Tolkien’s inclination to write constantly of the importance of food was also influenced by his harrowing experience during World War I. He served as an officer, and was certain he would die. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s vision of the ideal village is a land of parties and plentiful mushrooms, seemingly untouched by war. The Hobbit’s first chapter features unadventurous Bilbo Baggins turned on his head by the wizard Gandalf and a posse of hungry dwarves, who raid his pantry. “A little red wine, I think for me,” Gandalf requests. The dwarves call out for raspberry jam, apple tart, mince pies, cheese, pork pie, salad, cakes, ale, coffee, eggs, cold chicken, and pickles. Even though Bilbo balefully empties his house to feed the dwarves, it’s a sign of bounty that he has all this food to hand.

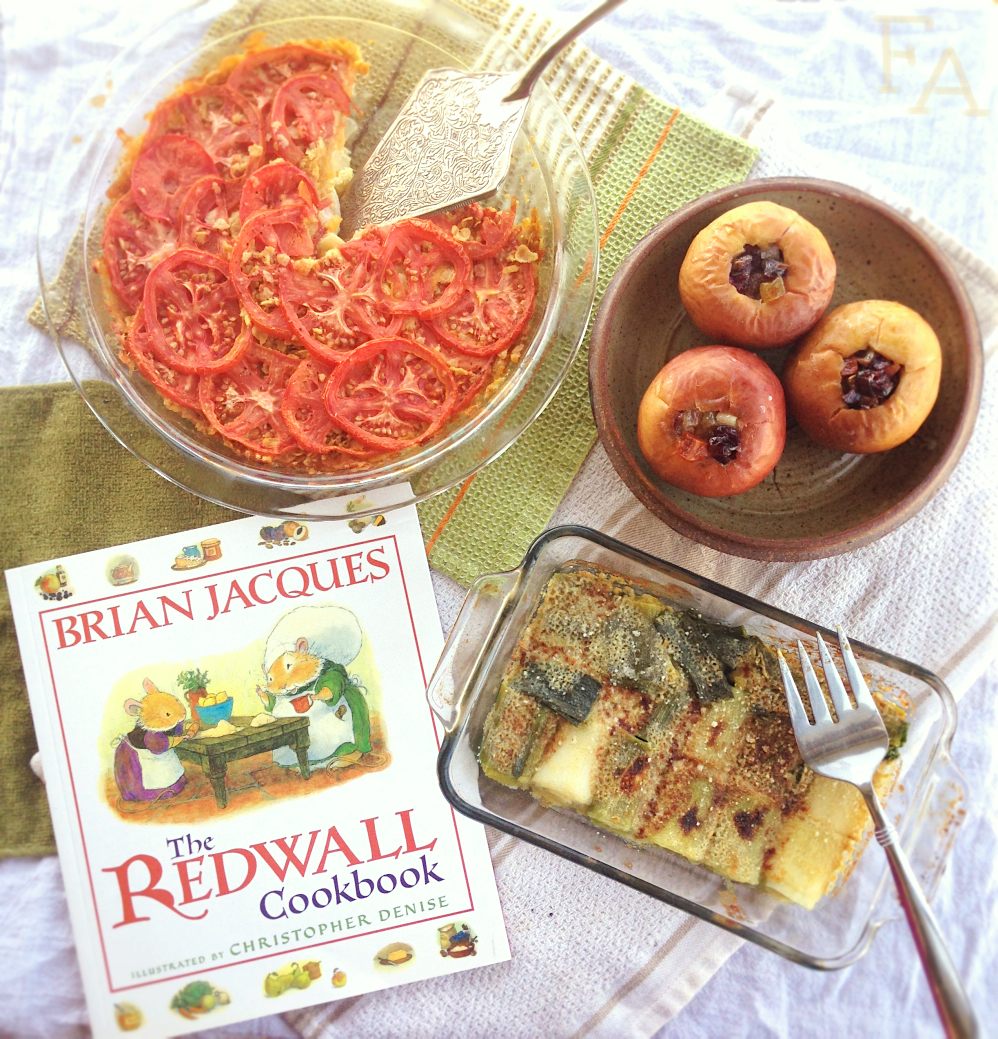

Another famed fantasy writer, Brian Jacques, was similarly shaped by war—in his case, by World War II. Jacques was most famous for his children’s fantasy series, the Redwall books. Throughout the 21 books, anthropomorphized animals fight evil and hold lavish feasts. Just one pages-long feast includes 12 kinds of salad, eight types of bread, 10 drinks, “fresh cream, sweet cream, whipped cream, pouring cream, custardy cream,” and a giant fish. In interviews Jacques said that his book’s fictional meals stemmed from childhood food fantasies during the years of British rationing. Many early readers enjoyed them for a similar reason.

As a preeminent fantasy author, Tolkien’s focus on food helped set the blueprint for fantasy writers. Middle-Earth’s ever-present cuisine and Tolkien’s style of food description also became standard due to its helpfulness in world building: Food works especially well at setting a scene.

Both Tolkien and Jacques fleshed out their worlds with history, songs, and distinct languages and dialects. To Maslen, food is another way to make fantasy seem real. “A lot of fantasy is set in other worlds,” he says. “Say you are writing a secondary-world fantasy. In that case, you want to make it as rich, as believable, as available to all the senses of your readers as you possibly can.” Songs appeal to the ear, frontispiece maps appeal to the eye, and descriptions of food appeal to readers’ stomachs.

Maslen believes food is one of the distinguishing features of fantasy literature. Whether its butter-pie or stew, food acts as an anchor against novels’ horror and high stakes. Fantasy writers, he says, “are very keen not to just induce horror and terror, but also wonder, surprise, delight, and amazement.” When challenging readers with the frightening and strange, food “anchors their experience in something they know well.” Even George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, which is known for breaking many fantasy tropes and traditions, still retains the requisite elaborate food descriptions (especially of soup).

Maslen offers an example from The Lord of the Rings, where Frodo and Sam share a meal on the border of Mordor, “right on the edge of the worst place in the world.” Even as their world-saving mission looms, Sam gathers bay leaves and sage to make rabbit stew. Amidst a beautiful, overgrown landscape, it’s a brief moment of wonder in the face of what Maslen calls “the most extreme example of the unfamiliar and the horrifying.”

In uncertain times, making comfort foods at the verge of calamity is certainly relatable. With such meaning imbued into the foods of fantasy, it’s no wonder that there are books and blogs galore devoted to painstaking recreations of lembas bread and cauldron cakes. This weekend, I’ll dig through them. Somewhere out there, I know there’s a recipe for butter-pie as wondrous as what I imagined 15 years ago.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook