In New Orleans, Crawfish Boils Can Be a Jewish Tradition Too

Even if it’s not exactly kosher.

On the last Sunday in May, as happens so often in spring in Louisiana, a room fills with tables covered in red-checked tablecloths and set with endless rolls of paper towel. In the center sits a plastic kiddie pool with a quarter-ton of crawfish, awaiting service with big metal scoops, like the kind you’d find in a hotel ice machine. Bright red, boiled through with local spices, ready for their tails to be pinched and their heads sucked, the ripe crustaceans await some 150 or more diners. What sets this crawfish boil apart is the location and the audience: It’s a fundraiser for the Brotherhood of Temple Sinai, held inside the Jewish synagogue.

Kosher law, the Jewish dietary guidelines, expressly forbid the consumption of shellfish. “All creatures in the seas or streams that do not have fins and scales … you are to regard as unclean,” declares Leviticus 11:9-12. But as is so often the case, the Torah doesn’t account for everything, most certainly not the settlement of Jews deep in the heart of Catholic Louisiana, where shrimp, pork, and shellfish drive diets, dinners, and community.

Temple Sinai is Louisiana’s biggest and oldest congregation of the Reform Jewish movement, a form of the religion with very little focus on keeping kosher. Instead of Jewish law, their priority, per their website, is “serving the spiritual needs of its diverse membership.” In general, the Reform movement is more about retaining a connection to Jewish learning and community than adhering precisely to the commands of the Torah—a 2013 Pew Study found that only 7 percent of Reform Jews in the U.S. keep kosher.

“New Orleans is a seafood town,” says Kenneth Hoffman, Executive Director of New Orlean’s forthcoming Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, “famous for delicious foods and the mixing of different cultures: Caribbean, African-American, etc. Throw in some matzo balls, and who knows what you’re going to get.”

While the Jewish diaspora spread congregations around the world, Hoffman notes that the American South was a particularly tough place to keep kosher. “It’s the prevalence of pork and seafood: it’s everywhere,” he says. The ubiquitous treyf (non-kosher food) was compounded by how Jews settled in the South. In the North, Jews concentrated in urban centers, in numbers that supported a kosher butcher and deli. But in the South, Jews tended to be isolated—a handful of shopkeepers in agrarian towns. The pressure for the small minority to be accepted led Jews to assimilate and acculturate. “You don’t want to stand out too much,” says Hoffman. “You already have a different religion; the last thing you need is to not be able to eat at your neighbor’s house.”

But there’s a difference between going next door for gumbo and hosting a crawfish boil in a temple. Stewart Yelton is a journalist and Alabama-born Jew. He’s now based in Hawaii, but he used to live in New Orleans and chair the Sinai Brotherhood’s euphemistically named “Seafood Bingo” fundraiser. He later wrote a novel called Crawfish Bingo, which fictionalized events and discussions around the annual dinner.

One plot point is based on a real incident: An NPR personality speaking to the congregation says, “Reform Jews might not keep kosher. But at the same time, no congregation today would ever think of having a shrimp boil at the synagogue.” Unaware of the Seafood Bingo tradition, he doesn’t understand the nervous titters from the audience.

The rest of the speech, however, is on point: It discusses the pendulum motion in the Reform movement, in which Jews are reclaiming traditions that they abandoned. Hoffman explains that the classical version of the Reform movement was very strong in the South, with its church-like organs, choirs, and lack of Saturday services. But now, yarmulkes and tallit (traditional hats and prayer shawls), once shunned, have begun re-appearing. Yet, so far, Seafood Bingo persists. “To reject Seafood Bingo,” observes Yelton, “would be to ask, ‘Were these people before us Jewish enough?’”

The rabbi who led the Temple during Yelton’s time recently retired. Yelton describes his thoughts on the event—which Yelton surmises is the synagogue’s second best-attended event after the High Holy Days (akin to trailing Christmas)—as quietly unenthusiastic.

Today, that seems to continue. The new rabbi and Temple officials, including the President of the Brotherhood (which runs the fundraiser), declined to be interviewed. The event has little internet presence, and even the name, Seafood Bingo, seems to purposefully obscure the flagrant violation of kosher law.

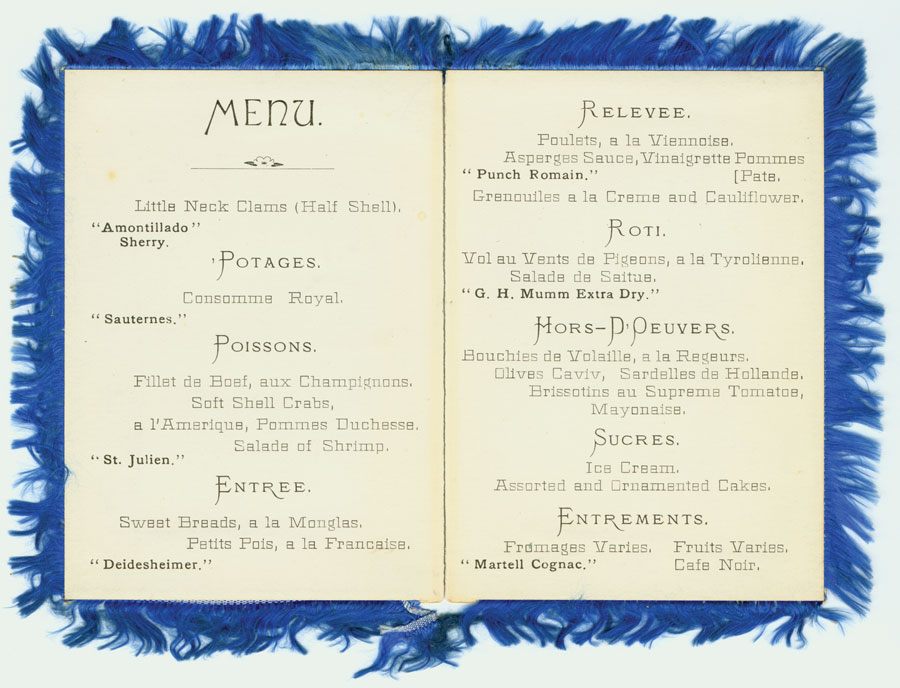

That said, New Orleans’ Temple Sinai is hardly the first Jewish entity to enjoy treyf. Following the ordination of the first class of rabbis of the Hebrew Union College (the oldest seminary of Reform Judaism), a banquet held in their honor kicked off with littleneck clams and continued with shrimp salad, soft-shell crab, and plenty of steak and cream—a violation of the kosher law that prevents the mixing of meat and dairy in one meal. But, explains Hoffman, the menu wasn’t meant to flaunt their non-observance. Scholarly discussion of the dinner notes that the organizers simply served foods typical for the time and place (1883 Cincinnati). It wasn’t all that different from celebrating spring in New Orleans with a crawfish boil.

Southern Jews have long enjoyed non-kosher foods—both in everyday and religious contexts. In her dissertation, Shalom Y’all: The Folklore and Culture of Southern Jews, Carolyn Lipson-Walker describes gefilte fish made of catfish (which is treyf), Shabbat dinners with pork chops, and a Mississippi temple’s “High Holy Day Shrimp Fry.” These dishes, she writes, “became so accepted in Southern Jewish diets that many Southern Jews growing up in mid-century [America] did not know that these foods were historically forbidden for Jews.” That timing lines up with the beginning of Sinai’s tradition: According to the Temple archives, kept in the Louisiana Research Collection at Tulane University, the Men’s Club (soon after re-named the Brotherhood) held its first seafood dinner in 1952.

The collection also holds samples of invitations through the years, including handwritten invitations and crabs and crawfish crawling around on a typewritten flyer. Budgets outline payment for a quarter-ton of crawfish, along with corn, potatoes, garlic, and crabs. A few pans of jambalaya, lasagna, and chicken round out the food, plus a keg of beer and plenty of Tabasco sauce.

As suggested by the NPR speaker in Yelton’s book—and the giggle that escapes most Jews when they hear of the dinner—the idea of a temple-budget line-item for shellfish is laughably absurd—which, in the grand Jewish comedy tradition of self-mocking, might be exactly the point. Lipson-Walker writes that “As Southern Jews became more savvy about Jewish culture and cuisine, they began telling humorous stories about themselves and their lack of knowledge about Jewish rituals.”

Yelton agrees that the famous Jewish sense of humor might have played into the tradition, guessing that it began from good-natured satire and “poking fun at themselves and their Catholic friends.” But Jews aren’t the only ones who like to make fun of themselves. Yelton adds that the tradition seems in keeping with the teasing, parodying traditions of the city’s most famous (and famously Catholic) tradition, Mardi Gras. Hoffman agrees that there’s something particularly New Orleans-ian about the Seafood Dinner: “We like being unique.”

Yelton chose to fictionalize the Seafood Bingo in his book in order to encapsulate what it’s like to be a Jew in the South—hence, he says, “the wacky novel and silly title.” More importantly, he says the reason he wrote the novel meshes with the likely reason Seafood Bingo continues on today: “It’s New Orleans: People like to have fun, and it’s a fun event.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook