One Man’s Search for the First Hebrew-Lettered Cookbook

The text is a snapshot of Hungary’s Jewish middle class in the mid-1800s.

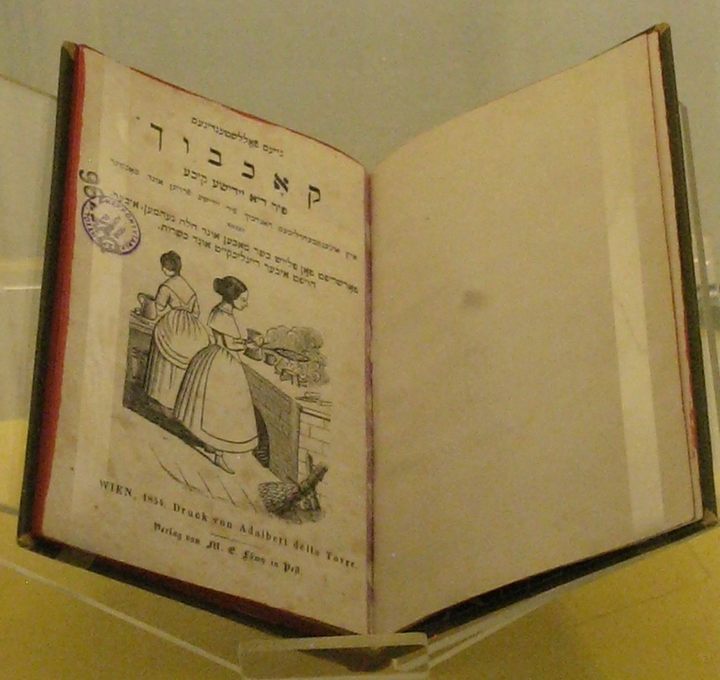

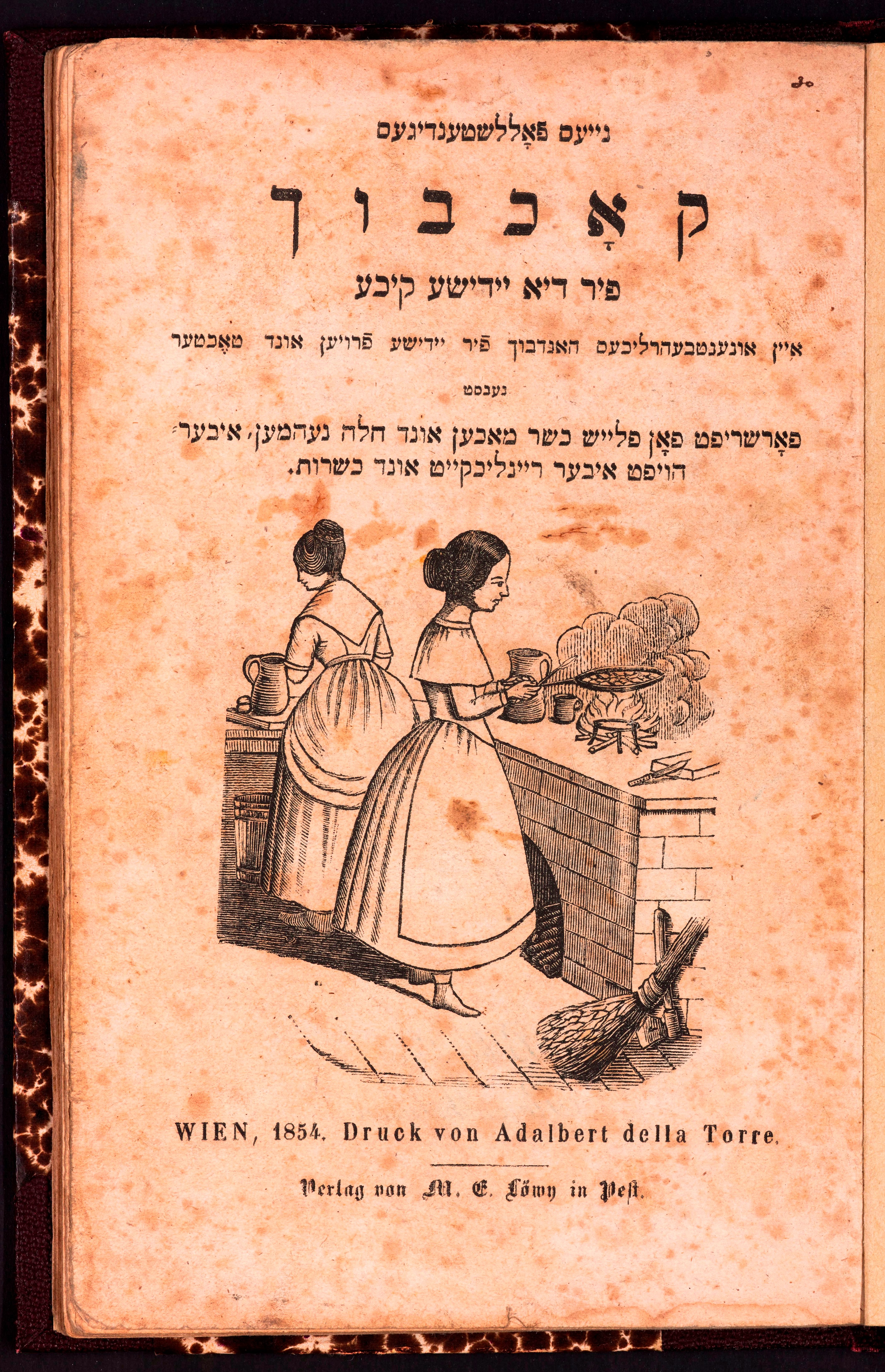

A few months ago, András Koerner, the foremost expert on Hungarian Jewish culinary history—finally got to see the treasure he’d chased for years. At the Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism, he beheld a 168-year-old book that, just a few years earlier, had been thought to have disappeared without a trace. Opened to its splotched first page, it was covered with Hebrew print and an illustration of women working over a countertop, one of them holding a pan over an open fire.

The pages ahead contained something that no Hebrew-lettered book before it ever had: recipes. This cookbook, published in 1854 in Budapest was 40 years older and of a completely different national origin than the book that historians had previously regarded as the first Hebrew-lettered cookbook.

“I don’t want to exaggerate it, but at least within scholarly circles, it was a small sensation,” says Koerner, author of this year’s Early Jewish Cookbooks.

Koerner, 81, grew up in a middle-class, Jewish neighborhood of Budapest after surviving the Nazi-occupied city’s ghetto. His quest to find the nearly 170-year-old book is part of a lifetime of connecting with his roots through food. In 2016, while doing research for his book Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, Koerner came across a reference to the 1854 cookbook in a bibliography.

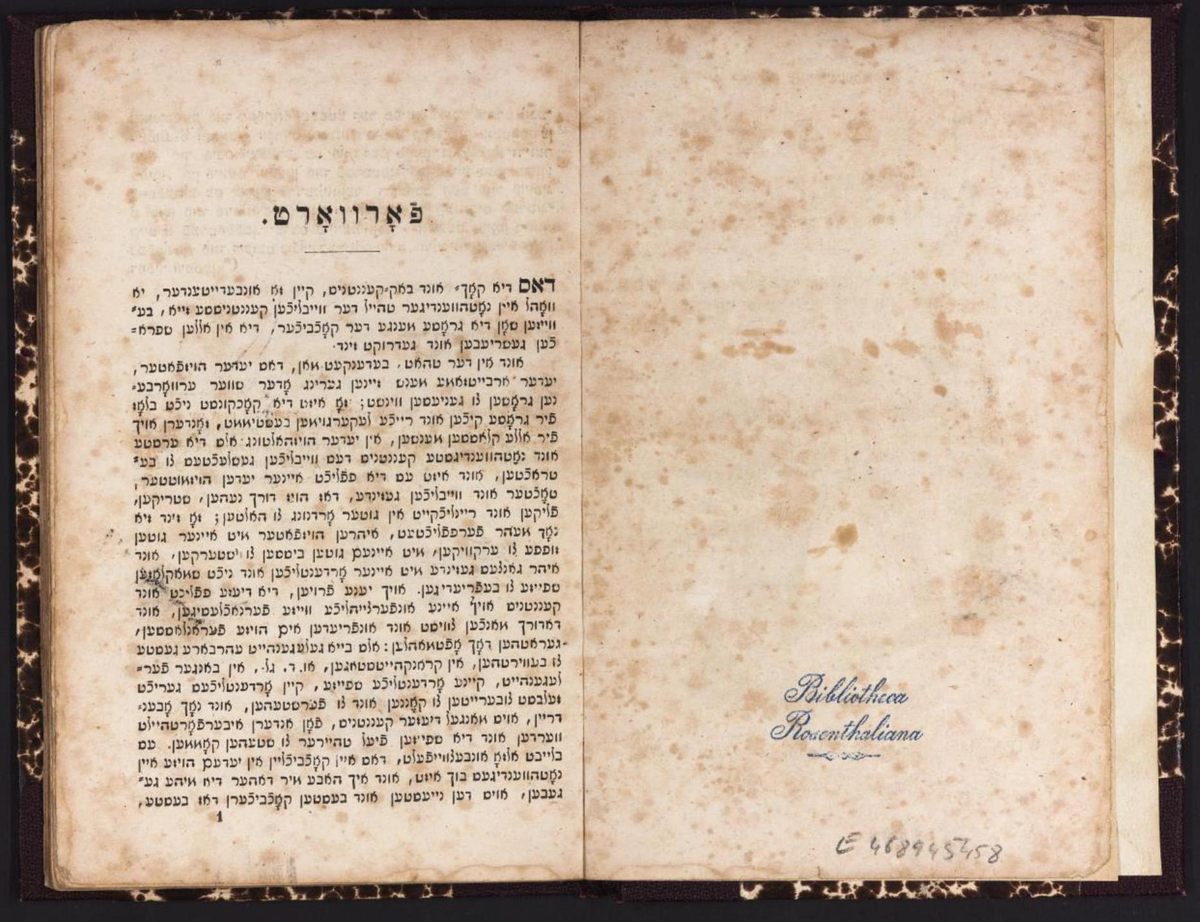

The bibliography noted that no copy of the book survived. But Koerner didn’t give up, following a trail of clues to a xeroxed copy of the book in a library at Budapest’s Eötvös Lóránd University. Several years later, a friend located what was then the only known surviving copy of the book in an online catalog of Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, a collection at the University of Amsterdam. But Koerner only glimpsed it from afar via digital scans.

The book, titled Nayes folshtendiges kokhbukh fir die yidishe kikhe: Ayn unentberlikhes handbukh fir yidishe froyen und tokhter nebst forshrift fon flaysh kosher makhen und khale nemen, iberhoypt iber raynlikhkayt und kashrut, or “A new and complete cookbook of the Jewish cuisine: An indispensable handbook for Jewish women and daughters, with instructions for koshering meat and separating challah, as well as for general cleanliness and kashrut,” is a surprising snapshot of a community in transition.

“It was like a microscopically minor scandal in the field,” Koerner jokes.

Koerner and other scholars had assumed that the book’s Hebrew letters spelled out words in Yiddish, which was widely spoken by European Jews in the 1800s and was typically written in Hebrew characters. But when Koerner asked a friend to translate the book into German, she returned with a revelation: The book was written in German, but spelled out in Hebrew letters. By printing the book in Judeo-German, as Hebrew-lettered German is called, its publisher aimed it at the newly emerging Hungarian Jewish middle class.

When Márkus Löwy, owner of the bookstore M.E Lowy’s Sohn (M.E. Löwy’s Son), published the cookbook, Hungary was exiting a period during which Habsburg, Hungarian, and municipal leaders participated in barring Jews from Hungarian cities, and the Habsburg ruler Maria Theresa subjected them to “tolerance taxes.” Law separated them from other Hungarians, and their traditions and Yiddish language isolated them further.

But in the mid-1800s, some Jews stepped away from their cloistered lives—and the Yiddish language that had narrated them. Beginning in the 1840s, the Hungarian Parliament granted Jews civil rights, including the right to own businesses and live in Hungarian cities, although they still were not permitted to own property there.

“By the middle of the 19th century,” Koerner says, “in Hungary there was a substantial [Jewish] middle class. And those were the people who purchased Jewish cookbooks.” A generally more rural, lower-income group of Jews had also settled in Hungary from Eastern Europe by then, but, Koerner says, “they could not have bought Jewish cookbooks, number one, because they did not have money for it…[Number two,] they would not have understood High German.”

At the same time, the Haskalah, also known as the Jewish Enlightenment, prompted a wave of reformist Jews to integrate into Hungarian society while retaining their religious traditions. “They started to imitate non-Jewish culture,” adopting the dress, education, and cuisine of their Christian counterparts, Koerner says.

Accordingly, Löwy’s 1854 cookbook is filled not with markedly Jewish recipes, but rather with kosher versions of fancy, Christian-Hungarian dishes, such as “Hungarian Goulash Meat,” “Root Vegetables in the Hungarian Way,” and “Soup Made of Fresh Cherries.” Koerner notes that the “Hungarian-Style Apple Cake,” which requires rolling out 25 loaves of dough and forming them into a layer cake, is exactly the type of elaborate Hungarian dish that a middle-class Jewish woman in 1854 might have admired.

Integrating into Hungary’s middle class meant speaking its dominant language and, eventually, abandoning Yiddish. But speaking German was one thing; reading it was another. “Even as late as 1870, only 75 percent of Jewish men and 58 percent of Jewish women could read and write in non-Hebrew characters in Budapest, the city with one of the highest levels of literacy among Hungarian Jewry,” Koerner writes in Early Jewish Cookbooks. During the 1700s and 1800s, publishers in Germany, Austria, and Hungary addressed this discrepancy by printing books in Judeo-German, transliterating German words with letters that Jews recognized from reading Hebrew and Yiddish books.

It’s likely that Löwy published his 1854 cookbook with this in mind, marketing it to women who preferred to speak German but could not yet read it. He even chose a Hebrew font called vaybertaytsh, which was associated with women’s Yiddish devotional books, to appeal to potential female customers, Koerner believes.

But Löwy was late to the game. He published only one edition of the book that never quite caught on. Koerner believes Löwy’s would-be customers had already embraced reading German text by 1854. This, Koerner thinks, is why so few copies of the book exist today.

The book’s rarity makes it all the more precious. Just before Early Jewish Cookbooks was published earlier this year, Koerner’s friend alerted him to another physical copy of the cookbook that was available at a private auction. Koerner persuaded Hungary’s National Library to purchase it. Right now, the book is on display as part of an exhibit on Hungarian-Jewish cuisine at the Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism that Koerner helped curate.

When Koerner was able to look at a physical copy of the book he had pursued for so long, it was an emotional experience. “It was wonderful. It was joyous,” he says. “And, honestly, if I want to brag, I was a little proud of it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook