American School Lunch Is Becoming More Diverse, Like It Was in the 1910s

The cafeteria program started in immigrant communities.

Alana Dao couldn’t figure out which was worse: going to school with a lunch box full of hummus, or pulling out Chinese pork floss buns in front of her classmates. In the 1990s, Sugar Land, Texas, was a steak and potatoes kind of place. In contrast, Dao’s parents were Buddhist vegetarians from China, who prepared traditional foods such as Cantonese eggs and meatless staples such as the Middle Eastern chickpea spread.

A food writer and restaurant professional, Dao now loves the cuisine she was once embarrassed by. Yet her writing sears with recollections of her childhood anxiety. In a sea of peanut butter sandwiches, her lunches marked her as racially different when she only wanted to fit in. “It’s pointing out difference at a time in your life when you don’t necessarily want to be different,” she says.

There’s a phrase for Dao’s experience: the lunchbox moment. While the food in these stories is diverse, from Filipino lumpia Shanghai to Cameroon peanut sauce, the emotional experience is similar: self-consciousness about cuisine whose supposedly “stinky” flavors signal racial and cultural difference. In these accounts, school cafeteria meatloaf and tater tots are symbols of a white American culture that rejects immigrant children.

The alienating symbolism of cafeteria food is as old as the National School Lunch Program. But it wasn’t always that way. While the National School Lunch Act was signed in 1946, the country’s first school food programs began decades earlier, in the immigrant tenements of turn-of-the-century cities. In these early lunchrooms, diversity ruled.

In 1908, Mabel Hyde Kittredge founded one of the nation’s first school lunch programs in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City. The program soon expanded to the Lower East Side. While the Manhattan neighborhood is now home to haute couture and exclusive real estate, at the time, it consisted of cramped tenements brimming with poor immigrants. From 1880 to 1920, more than 20 million immigrants entered America, most of them from Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe. Thousands of them settled on the Lower East Side.*

At the same time, progressive reformers were devoting themselves to the plight of the urban poor. Armed with new scientific theories about health, and inspired by the shocking revelations of muckraking journalists, these reformers—many of them middle class white women trained in domestic science—set about bringing modern nutrition to the slums.

Yet early efforts to establish food programs in these impoverished communities failed. The programs were based on the latest nutritional science, but they lacked one thing: flavor. “Regard seemed not to have been paid to the religious and national customs of the children,” wrote activist Lillian Wald.

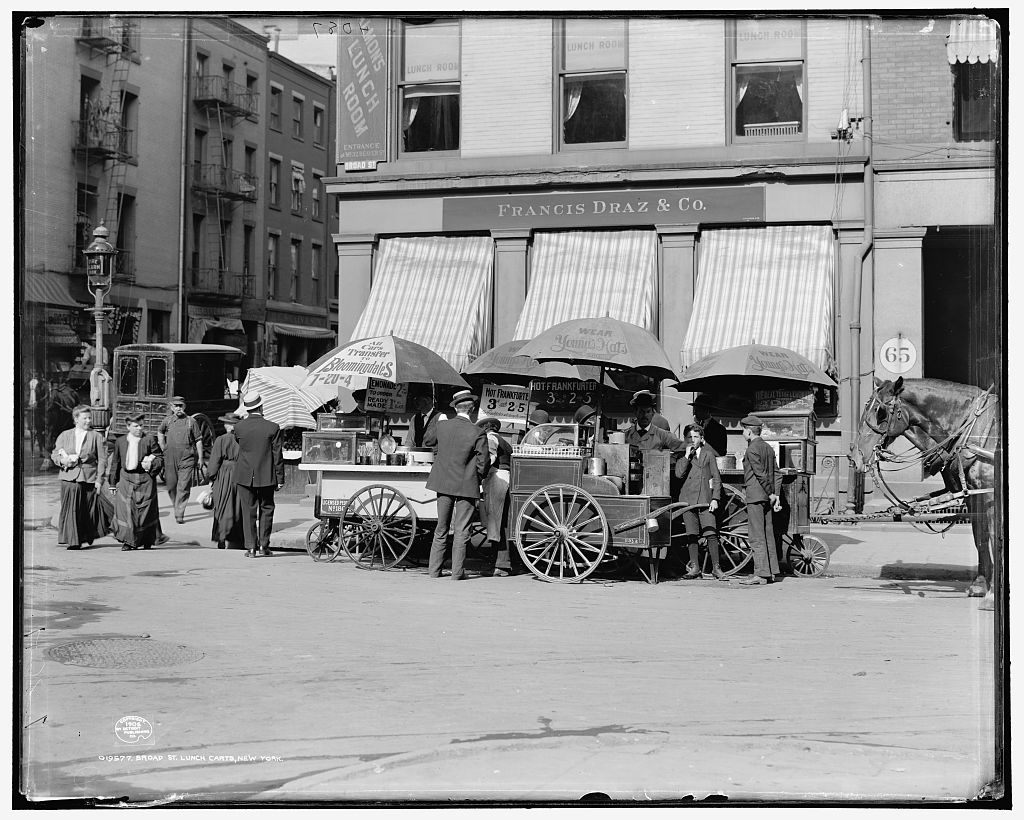

When Kittredge founded the private School Lunch Committee in 1909, she did something different: She adapted her vision of modern nutrition to the flavors of the Lower East Side’s Jewish, Irish, and Italian kitchens. At the time, students were expected to go home for lunch—a difficult proposition for parents whose paltry factory incomes were barely enough to feed the family. Children who didn’t go home often purchased food from unsanitary street carts. As a result, kids in these communities were widely malnourished and often ill. Kittredge’s SLC changed that by offering low-cost and nourishing meals that tasted like home cooking.

In majority-Italian schools, the SLC offered macaroni and used garlic and oil. In Jewish schools, the SLC invited rabbis to inspect the kitchens. When American cooks failed to capture cuisines’ authentic flavors (“You Americans take all the nerve out of our macaroni,” an Italian girl told Kittredge), the program hired Italian and Jewish cooks instead.

At first, immigrant families were wary of the new program. “The mothers would come in large numbers to watch the food service to make sure the food was okay,” says Michelle Moon, Chief Program Officer at New York City’s Tenement Museum. But soon, families began to trust the cooks and even take home recipes. For poor people far away from their native ingredients, these programs became a kind of culinary exchange.

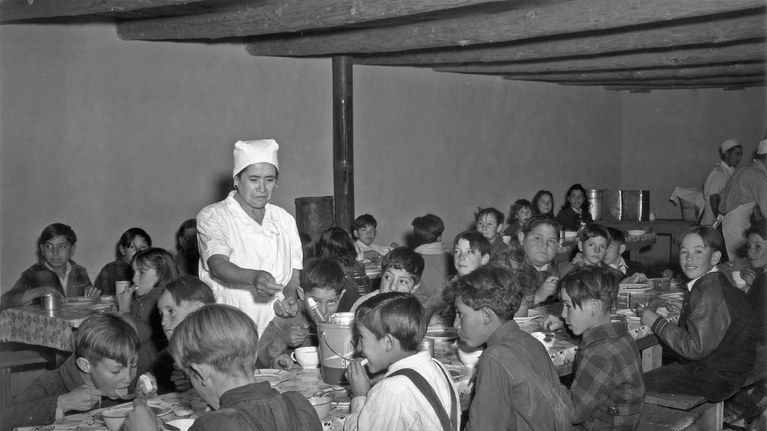

The approach worked. By 1915, the SLC was providing 80,000 free or low-cost meals in 60 schools across New York City. Educators reported their charges were healthier and more attentive in class.

But the success didn’t last long. When New York City officials, long reluctant to make school lunch a public service, took over the program in 1917, they dramatically cut the funding. By 1919, the city had cut the program to just 14 schools, with food provided by private contractors.

The government program imposed one menu on the entire city—and it was stubbornly, blandly American. Whereas children had previously enjoyed Kosher food and minestrone, they were now served a uniform, city-wide menu of baked beans, pea soup, and oatmeal cookies. For immigrant families, the shift was abrupt. Italian immigrant Leonard Covello writes in his memoir that when his school gave him a bag of oatmeal to take home, his father thought it was animal feed. “What kind of school is this?” Covello’s father shouted. “They give us the food of animals to eat and send it home with our children!” (Covello had his own lunch box moment when he hid his Italian-bread-and-salami sandwiches for fear his friends “of the white-bread-and-ham upbringing” would make fun of him.)

While this shift was partly motivated by finances, says Andrew Ruis, a University of Wisconsin researcher who wrote a history of school lunch, it also reflected growing anti-immigrant sentiment. Nativist prejudice against Italians, Irish, Jews, and all non-Europeans had long been apparent in laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act. It grew worse during World War I. The Immigration Act of 1917 imposed a literacy requirement and banned Asian immigration almost entirely. The Immigration Act of 1924 established nationality quotas that vastly favored Northern Europeans.

When the National School Lunch Program became law in 1946, this anti-immigrant legacy came with it. During World War II, the federal government had formed the Committee on Food Habits, headed by famed anthropologist Margaret Mead, to determine best practices for a national school lunch program. While ethnic diversity was fundamental to America, Mead asserted, the school lunch program should create a unified national identity. Instead of eating their own ethnic cuisines, students should “eat democracy.”

Democracy was rather bland. Mead recommended that school lunch menus consist of “food that is fairly innocuous and has low emotional value.” Spicy foods, cream sauce, and strong flavors were out; meat pies, plain soups, and boiled vegetables were in. The only seasoning would be salt.

Mead’s vision of “innocuous food” had a fatal flaw: lack of seasoning doesn’t actually mean neutrality. Although Mead’s guidelines payed lip service to diversity, their imposition of a standard diet ultimately implied that bland foods were properly “American,” while other foods—whether spicy or “stinky”—were alien. Seven decades after the National School Lunch Program became law, immigrant kids continue to face prejudice for eating food their peers consider “too ethnic.” Their lunch box moments are reminders of an assimilationist legacy.

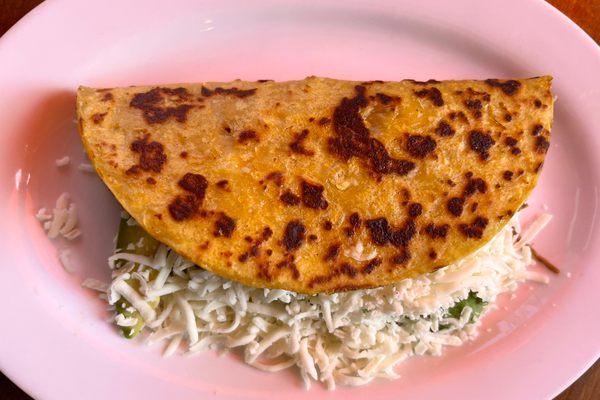

This is starting to change. Over the past decades, activists and school districts have increasingly promoted scratch cooking and locally sourced foods. Meanwhile, cafeterias are modeling menus after the cultures of the kids they serve. With USDA support, indigenous Hawaiian children are being served taro and Native Alaskans are eating local fish. In Austin, public schools are serving local Mexican cuisine. In Des Moines, “flavor bars” allow students to customize their food—from pinto beans to sweet and sour chicken—with familiar spices. In Burlington, a student-run food truck draws on the diverse community’s culinary suggestions and skills.

Dao’s own relationship to food and heritage remains complex. While she now treasures the Cantonese eggs and pork buns she once hid, the effects of prejudice linger. Some days, she hesitates before packing her daughter’s lunch with food she fears other children will consider stinky. “I don’t want to embarrass her,” she says.

In the past couple years, though, Dao has found herself feeling less apologetic. She wants her two daughters to be strong and unashamed. “This is who we are,” she says. Recently, Dao’s grade school-aged daughter asked to take smoked oysters to school. Remembering her own childhood discomfort, Dao’s first instinct was to say no. But her daughter insisted, and Dao relented. When her daughter returned in the evening, Dao nervously asked her about lunch. But her daughter was nonchalant—it was just another school day. As for the lunchbox? “It came back empty—and smelly,” Dao says. Only now, that scent was something to celebrate.

*Correction: A previous version of the article conflated Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen and Lower East Side. They are distinct neighborhoods.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook