In Shakespeare, Food References Are a Window to the Soul

Decoding a character’s anger over roast mutton.

In Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, the protagonist, Petruchio, attempts to tame the hot-headed “shrew” by unceremoniously disposing of her dinner. Plates clatter to the ground as he snatches a leg of roast mutton from her hand. “It engenders choler, planteth anger,” he cries, as he suggests “better ’twere both of us did fast.”

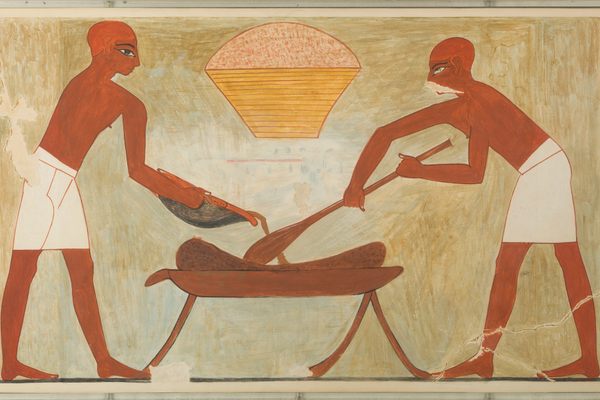

How could a leg of roast mutton fuel anger? For Elizabethans, food and drink was more than mere sustenance. Eating the right foods in the proper quantities, 16th-century Britons believed, balanced mind and soul. So in Shakespeare’s plays, roasts, ales, and pies are not props, but clues to characters’ souls, moods, and motivations.

The key to decoding these clues lies in understanding the medicine and science of the (pre-Scientific Revolution) era. Shakespeare’s peers still hewed to the 2nd-century theories of the Greek physician, Galen, who believed the balance of four humors (categories of fluid) corresponded to different temperaments. A surplus of blood meant a person was sanguine, too much black bile made someone melancholy, yellow bile meant you were choleric, and an oversupply of phlegm caused one to be, naturally, phlegmatic. Foods could sway this balance—roast mutton, for example, was considered hot and dry, spurring choleric (irritable) temperament. Which is why Petruchio deprived hot-tempered Katherine of her mutton.

Shakespeare’s characters often personified a specific temperament. Hamlet and Ophelia, who exude melancholy, should avoid tart or sour foods such as lemon and vinegar in favor of sanguine (moist and warm) foods such as basil, butter, and, apparently, peacock. Yet, in his grief over Ophelia’s death, Hamlet claims he will drink vinegar, though it will exacerbate his melancholy, to prove his love for her.

But in Shakespeare’s world, as in Elizabethan society, one culinary imbalance reigned above all others: gluttony. Beginning in the fourth century, gluttony topped the list of cardinal sins (the seven deadly sins). Early definitions even offered five different ways to commit the premier sin, including eating too soon, too much, too eagerly, too lavishly, or too daintily. As the “forechamber of lust,” gluttony could also lead one to committing the six other deadly sins: pride, lust, wrath, envy, greed, or sloth.

Many Shakespeare characters were gluttonous, but few equalled the corpulent Sir John Oldcastle, known as Falstaff. A lover of anchovies, capons, and sak (a sherry-like sweetened wine), all foods to be avoided for his phlegmatic temperament, Falstaff epitomized both the humoral imbalance and sin of gluttony. According to Shakespearean scholar Dr. Joan Fitzpatrick, as a large man during a period of food scarcity, Falstaff’s indulgence in food, drink, and carousing signified selfishness that corresponded to his cowardly and irresponsible behavior. In fact, Shakespeare provides a lesson about moderation when the soon-to-be King Henry V must reject Falstaff to become a virtuous ruler.

However, Shakespearean society is equally suspicious of another form of gluttony: fasting. People who do not enjoy the pleasures of food and drink, especially those who refuse hospitality, were seen as flaunting the masochistic pleasure to be had in depriving the body. In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Slender, a thin man characterized by his refusal to accept food or drink, is portrayed as dim-witted. In 15th- and 16th-century England, providing food, shelter, and entertainment to guests was a way to maintain neighborly relationships and make connections across social orders. Hospitality demonstrated generosity and virtue, so while feasting could be sinful, it had a positive side, too.

From Hamlet’s leftover “funeral baked meats” to Twelfth Night’s “cakes and ale,” Shakespeare mentions food in every one of his plays. Like the real-life experiences of his contemporary audience, these are not just dinner parties or polite conversation, but moments that reveal virtue and sin.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook