The Forgotten Female Artist Whose Mardi Gras Fantasias Warped Reality

If only Jennie Wilde could have transformed society too.

If you stood on Canal Street in New Orleans on the night of February 28, 1911, you would have seen green monsters rolling on a sea filled with giant poppies, grapes the size of your head, and deep-pocketed businessmen in glittery nymph costumes waving at the assembled crowd.

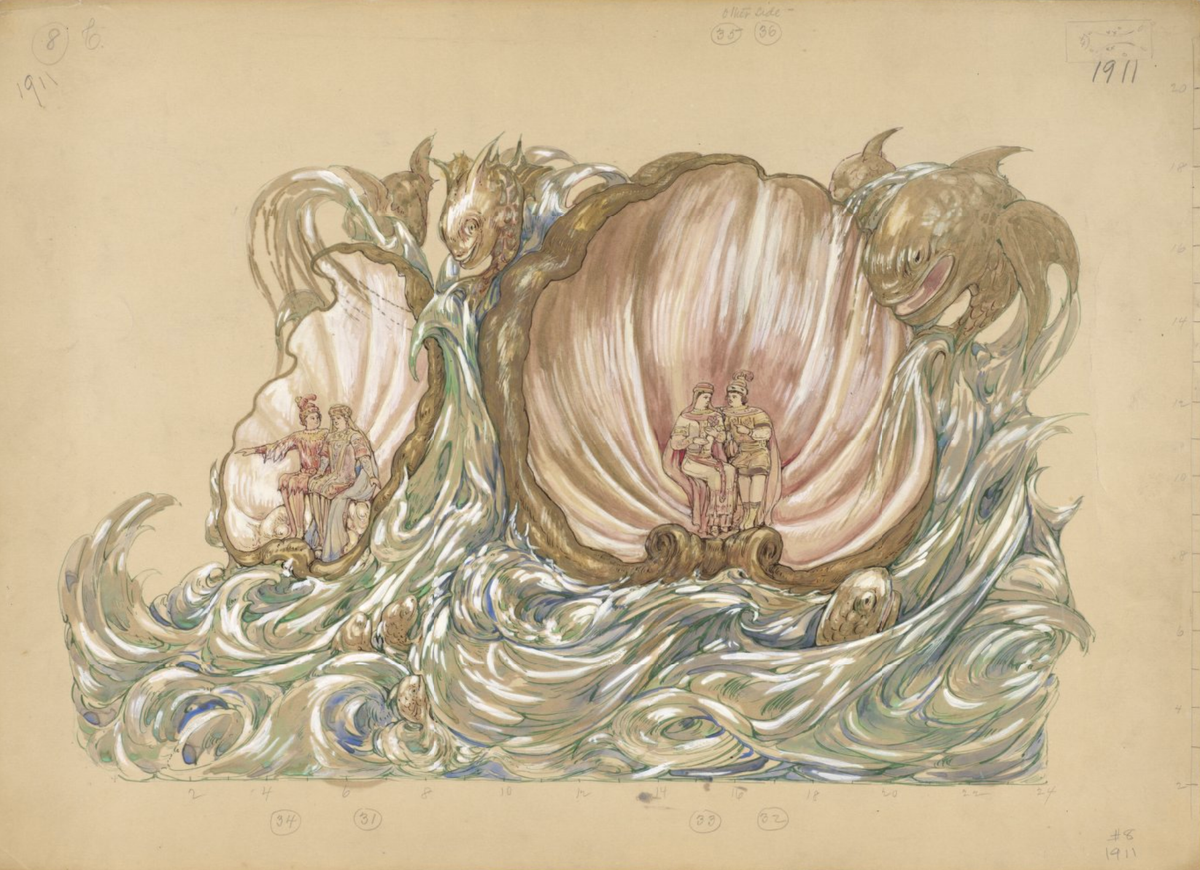

For Jennie Wilde, a designer responsible for two decades of artfully outlandish Mardi Gras spectacles, that was “such stuff as dreams are made on”—her spin on Shakespeare’s famous line, interpreted for the 1911 “Familiar Quotations”-themed Mardi Gras parade. That year, Wilde designed 20 original floating set pieces and approximately 100 costumes—fabric fantasias that allowed the richest men in Louisiana to forget themselves for an evening and revel in a dream world. (Though most of New Orleans donned costumes for Mardi Gras, only wealthy white men were permitted to ride on parade floats.)

Yet Wilde was never publicly credited for her groundbreaking designs. Her name was absent from the glowing press coverage of the annual festivities, and left off the illustrated broadsides that parade-goers snatched up for a dime. Back then, the making of Carnival (the local term for Mardi Gras) was a secretive affair, kept under wraps by the wealthy social organizations, called krewes, that funded it. Each krewe concealed its membership rolls and staff artists’ names, as a way to both preserve mystery and keep its inner workings free from public scrutiny.

The intervening years haven’t been much kinder to Wilde, publicity-wise, or more revealing. Though Tulane University published 5,500 Mardi Gras watercolor sketches—many of them Wilde’s—from its digital archive in 2012, she remains an obscure figure today. Yet without her acrobatic imagination and prolific, Art Nouveau-ish work—at a time when float and costume design was dominated by men—many of the era’s greatest artistic achievements would never have come to pass.

The trove of original watercolor designs published by Tulane showcase Wilde’s unique ability to transform krewe members into royals, gods, demons, women, or whatever else they fancied. For years she provided these wealthy white men with make-believe wardrobes any 6-year-old would be thrilled to wear: heavily beaded capes with lemon-yellow lining, scepters with dangling strings of stars, crowns packed with jewels.

As today’s designers prepare their floats and costumes for next year’s Carnival, Wilde’s story, set in a competitive world of secretive, exclusionary clubs and rival designers, deserves a fresh appraisal—and a front-and-center place in the history of New Orleans’ biggest party.

Born in Georgia in 1865, Virginia Wilkerson Wilde (known throughout her life as Jennie) lived and worked in what many historians consider the golden age of Carnival—the period that stretched from the late 19th century to the early 1930s, when krewes spent big money trying to outdo one another in the pre-Lenten party business. (Each krewe reportedly spent more than $25,000 a year—an eye-popping $660,000 in today’s dollars—on the annual public parade and an invitation-only masked ball.)

Wilde was born into a prosperous, artistic, socially prominent Catholic family. Her grandfather was a statesman and the poet laureate of Georgia; both her father and brother were writers. Wilde dabbled in writing herself, but trained as a painter at the Art League of New York.

When she returned to New Orleans, she got her own small studio and found work as a muralist for local churches. Then, in 1891, the 25-year-old Wilde was tapped by the oldest of the Mardis Gras krewes—the Mistick Krewe of Comus—to design invitations for the club’s demon-themed ball. That Comus gig secured Wilde steady work until she died—in 1913, at age 48—while on a trip to England.

Distinct from her contemporaries, Wilde’s art shows an unabashed more-is-more ethos coupled with a Catholic’s respect for ornamentation. With more flowers, more jewel-toned clouds, and more strings of stars, her floats were mesmeric accumulations of detail. She loved the unruly, natural curves of Art Nouveau, a movement inspired by the sinuously lined botanical illustrations and Japanese prints that were sweeping Western markets in the late 19th century.

“Wilde became Carnival’s high priestess of Art Nouveau,” writes designer and historian Henri Schindler in his book Mardi Gras Treasures: Costume Designs of the Golden Age, “and the float plates of her maturity were animated by her hallmark dynamic energy—by turns elegant, frenzied, and spellbinding.”

Also unlike other designers, Wilde was equipped to handle her krewe’s most erudite assignments. Each spring, just after the glitter had settled from February’s Carnival parade, the Krewe of Comus would assign her the next year’s theme. Wilde would take it from there. “I am given simply the name of the subject and have to think up, read up, imagine, and then design floats, costumes, invitations, tableaux, souvenir pins, dancing programs, and further arrange the plates for the newspapers,” she explained.

The Krewe of Comus distinguished itself from other clubs with its classically themed floats, and directed Wilde to concoct sets based on world mythology, religion, and literature. Over the years, she managed to coax dynamic costumes and visuals from a diverse set of themes—from the life of the prophet Muhammad to obscure medieval love stories to the poetry of Lord Byron.

Wilde’s floats were built “from the wheels up,” says Schindler. (Today, the same basic structures are reused repeatedly.) In her sketches, krewe members, caped and helmeted, looked down from bronze piles of swords and shields in the “I Came, I Saw, I Conquered” float. They lounged inside pearly shells atop a turbulent sea in a “What Are the Wild Waves Saying” float (its title drawn from a popular 19th-century duet). And they cavorted among so many stars and dewdrops in Wilde’s “All That Glitters Is Not Gold” float that one New Orleans newspaper used nearly every known synonym for “shining” to describe it.

Yet behind all this beauty and whimsy was something much darker. The golden age of Carnival was not the golden age of inclusivity. Even as krewe members played with their own identities—gender, race, even species—on Carnival night, they kept their prejudices front and center. Jews, Italians, and African-Americans—no matter how much money they may have had—were never permitted to join the Carnival krewes. And as a woman, Wilde was allowed to work only behind the scenes.

Some krewe-commissioned costumes of the time were explicit parodies of sex and race. One year, before Wilde became the Krewe of Comus’s main designer, the club put on a “Missing Links” parade that satirized Darwin’s groundbreaking theory of evolution with papier-mâché costumes that included a banjo-playing gorilla. In 1877, the krewe lampooned a future where women (or men dressed as women) could vote, and men kept house, in a float titled “Our Future Destiny—1976.”

Fortunately, not all of these old-line krewes made it to the late 20th century they so feared. In 1991—after New Orleans passed an ordinance requiring krewes seeking a parade permit to publish their membership rolls, to prove that they didn’t discriminate on the basis of sex or race—the Krewe of Comus decided to stop parading altogether.

Looking through the lens of Mardi Gras and its artistic, largely forgotten designers, we can see the best and worst of New Orleans—and America—during this time period. The story of Wilde’s work is also the story of a prejudiced society, where only certain members—male, pale, and well-to-do—were allowed to transform themselves each year at Mardi Gras.

Yet Wilde—a marginalized woman who helped prejudiced white men play dress-up and flex their wealth and power—managed to create art that astonished the public for years. You didn’t have to be in a Wilde costume to be delighted by her work. In fact, if you were standing on Canal Street on a Carnival night, you would have received a priceless gift from this long-overlooked artist—entry into a poetic and glittering new world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook