Found: A Shipwreck That Solved a Decades-Old Maritime Mystery

The “mystery tug boat” was a U.S. Navy ship that had disappeared without a trace in 1921.

A sonar image of the mystery boat. (Photo: NOAA/Fugro)

They called it the “mystery tug boat.”

In September 2014, a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was on an expedition in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, looking for shipwrecks, when they found the wreck. On every search, the agency’s shipwreck hunters had a set of sites they were interested in exploring, and this one was a high priority. They had been given a tip that a wreck might be there, but they had little idea what they might find: there were no reported shipwrecks in this area—at least, not of a boat as large as the one on the sonar image they’d been given.

When they dove down and got a closer look at it for the first time, they knew, immediately, that it was a seagoing tugboat. It had a metal hull, and though the upper deck had collapsed, the boilers, the anchor and the engine were all still there. They determined that it had been powered by coal, which dated it to the late 19th century or early 20th. The ship was large for a tugboat—170 feet in length—and even after the team had examined it, they did not know what to make of it.

“We were mystified by this wreck,” says Robert Schwemmer, NOAA’s West Coast Regional Maritime Heritage Coordinator. It wasn’t in their database of reported or known wrecks. The question haunted Schwemmer and James Delgado, NOAA’s director of maritime heritage. What was this shipwreck? What was its story?

An artist’s image of the wreck. (Image: Artist Danijel Frka © Russ Matthews Col.)

Schwemmer’s job is to find and inventory shipwrecks in the west’s National Marine sanctuaries: in the Greater Farallones sanctuary, which extends from San Francisco’s Golden Gate out into the coastal waters, there are more than 400 wrecks. Three years ago, no one had ever systematically explored these waters in search of these historical sites; after Schwemmer and his colleagues were given the funding to search and catalogue the area, they kept finding new shipwrecks, too.

There was the SS Selja, whose fatal collision spurred updates to maritime law, and the Noonday, which was hidden by the mud in the ocean floor. There was the SS City of Rio de Janeiro, which carried its passengers all the way from Hong Kong, before it sank just outside of San Francisco Bay. There was the Ituna, which no one had seen in 95 years. The iron plates of its hull had peeled off and were gone, but its distinctive bow was still instantly recognizable.

Most of the shipwrecks in this sanctuary date to the late 19th and early 20th century. There are Gold Rush-era boats made of wood, most of which has been consumed by time, leaving behind spokes, anchors, chains and cargo. There are steel-hulled steamers, too, including one that’s inverted on the seafloor.

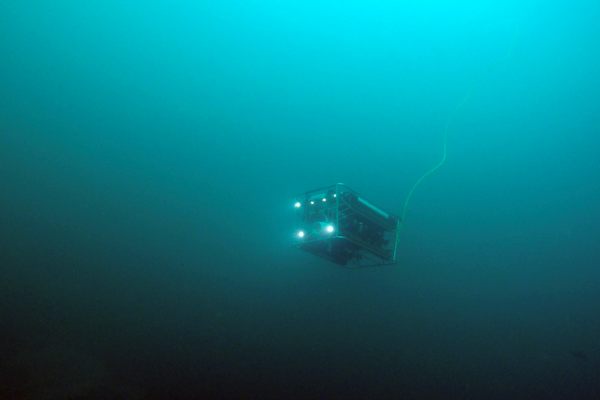

To find and identify wrecks, NOAA’s shipwreck hunters begin with sonar data that they gather from federal sources, state agencies and private companies. (The survey data that led them to the Ituna, for instance, came from a private company that had been paid to survey the seafloor for yacht that had disappeared without a trace.) They create list of targets, take out a boat, and investigate, by diving down to the site or sending remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) that can take footage or explore small spaces that people can’t go.

A gun base on the wreck. (Photo: NOAA ONMS/Teledyne SeaBotix)

It was footage from an ROV that ultimately held the key to the mystery tug’s identity. Schwemmer had started looking for reports of ships that had disappeared without their fate being known, and he came across a 1921 article about a tugboat gone missing, the USS Conestoga. That ship was in his database, but it was said to be sunk off of Hawai’i. He kept researching the boat, though, and found another clue: the boat had been headed for Hawai’i, from San Diego, but on its way, it went to Vallejo, in the San Francisco Bay area, for repairs. Also, it was the right length: 170 feet.

Maybe it hadn’t gotten that far.

In his research, Schwemmer had turned up a picture of the Conestoga. It had started life as a commercial tug, but had been bought by the U.S. Navy for service in World War I. In the picture, taken not long before the boat disappeared, it had been outfitted for war, with a couple of smaller machine guns.

The Conestoga. (Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command NH 71299)

Schwemmer had hours of footage of the mystery tug, taken by several different cameras on ROVs. If this was the Conestoga, there should be a gun somewhere on the ship, and Schwemmer started searching through the footage, seeing if he could catch a glimpse of a gun. Finally, he saw a ghostly image that “for a second, looked like the base of a gun,” he says. He went frame by frame through the footage. There was the base. There was the gun.

He called Delgado, who was getting ready for bed, and told him to get on the computer. Schwemmer sent over a still of what he had found, and Delgado said what he was thinking: “Oh my god, Bob, we have the USS Conestoga.”

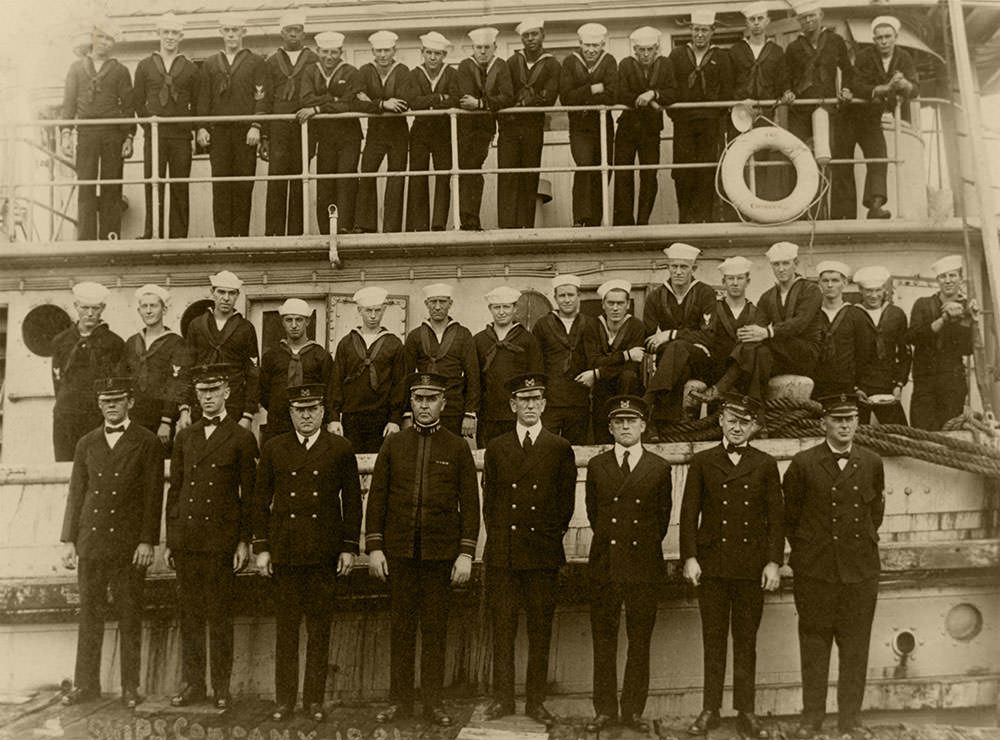

The crew of the Conestoga. (Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command NH 71503)

When the Conestoga disappeared, it was the last U.S. Navy ship to be lost, without explanation, during peacetime. Planes and ships were sent out to find it, in the largest air and sea search in Navy history until the hunt for Amelia Earhardt. But for almost 100 years, it remained lost. One of the most satisfying parts of finding and identifying the wreck, Schwemmer said, was being able to tell the families of the men who went down with the ship what had happened to them. The NOAA team believes the boat was fighting 40 mile per hours winds and rough seas and was attempting to reach a protected cove when it sank.

The funding for searching the Greater Farallones for shipwrecks will soon run out, but there are still mysteries out in the waters. Schwemmer has found a more modern fishing trawler, for instance, that’s still puzzling him, and there could be more unidentified ships out there. “Once you started getting out in federal waters that are major patches that have not been mapped,” he says. “There’s a just a lot of unexplored area out there.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook