A Map of the World’s Mammals for People Who Liked to Wear Them

This 1917 chart was focused on fur for fashion.

The winter of 1917 and 1918 was bitterly cold in New York City. In December, the meteorologist in charge of a local weather bureau described the “sleighing” as “excellent and continuous,” but winter wonderlands were not on the minds of city dwellers battling frozen pipes and streets slick with ice. That same season, furriers, stores, and catalogs in New York and beyond were busy trying to convince people that they could be a whole lot warmer, if only they would bundle up in fur.

For the past several decades, clothes and jewelry had become increasingly heavy with animals. In the 1880s and 1890s, “it was fashionable to trim garments and accessories not just with fur and feathers but also with taxidermied elements—for example, whole stuffed mice and cat’s heads,” says Marina Hays, a fashion historian and conservator whose current research focuses on fur and leather in fashion. Think earrings embellished with the small, iridescent heads of honeycreepers, or a muff made from the heads and necks of herring gulls. Press coverage of these styles wasn’t always positive, Hays adds, but it’s not so clear whether that was from aesthetic or moral outrage. As the 20th century entered its teens, conservationists began to take aim at the fashion industry’s use of creatures, particularly ones such as herring gulls that were wobbling on the edge of extinction, leading to debates and even legislation. Fur might have drawn less attention than feathers at the time, but, Hays says, “There were certainly people thinking about and acting on related moral issues.”

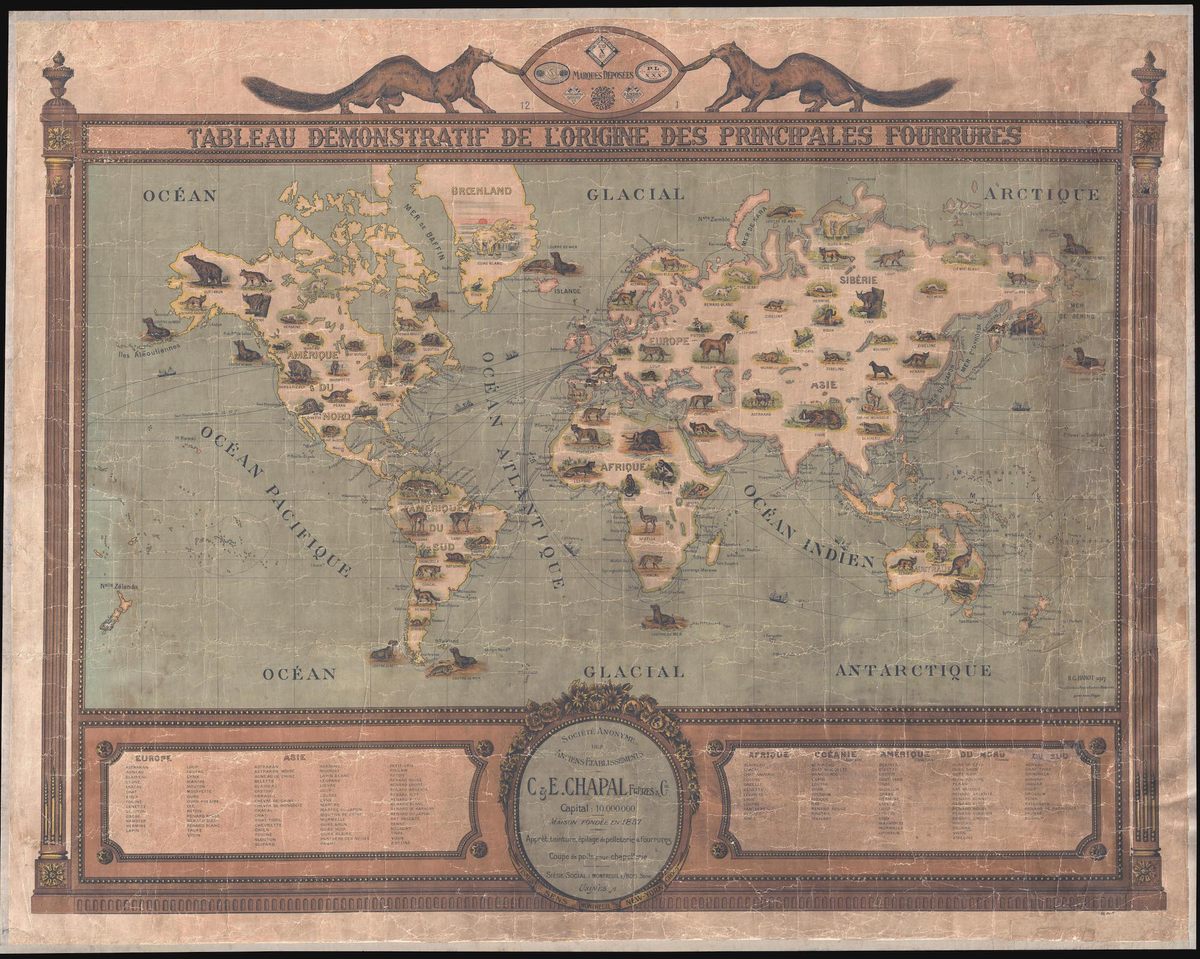

Meanwhile, fur was offered as a solution to the era’s drafty homes and cold rides in cars open to the elements, says Sarah Byrd, a fashion historian and educator. In 1917, to promote its business, the furrier known as C. et E. Chapal—a French outfit with branches in Montreal, Sens, Paris, and Brooklyn—issued a handsome pictorial map that charted the continents by the animal fur that could be collected on each one.

Pictorial maps were just gaining attention, and would burst onto the cartography scene in a big way in the following decades. They weren’t strictly scientific, but instead mingled landscapes, terrain, images, and text “frequently for the purposes of telling a visual story or to capture a sense of place,” writes geographer Stephen J. Hornsby in Picturing America: The Golden Age of Pictorial Maps, which draws upon a trove in the Library of Congress to describe the charts’ place in the canon of Western cartography.

These heavily illustrated maps are no good for navigation, but their makers used them to communicate specific information. “The style [of the Chapal map] was probably inspired by French maps issued in the late 19th century by Andriveau-Goujon, Vuillemin, and others, that used pictorial vignettes on city and world maps to promote tourism and display ethnographic content,” writes Kevin Brown of Geographicus Rare and Antique Maps in a description of the fur map. Geographicus is selling the Chapal chart, and calls it “one of the earliest modern pictorial maps we have seen.”

The Geographicus team hasn’t been able to track down much information about the mapmaker, noted next to Antarctica as one H. G. Hanot. Even so, Byrd suspects that the map’s size is a hint about how it might have been used. Laid on linen, it measures roughly three feet tall and four feet wide, so it may have been meant to be mounted on the wall of a showroom or sales office. “You’d bring in the fur buyers from the department stores, and they can see this beautiful illustration of where the sources are,” Byrd says. It could also have been a tool for training sales people, she adds, “so they could say to anybody who’s passing through the doors, ‘I know what this animal is, and where it comes from.’”

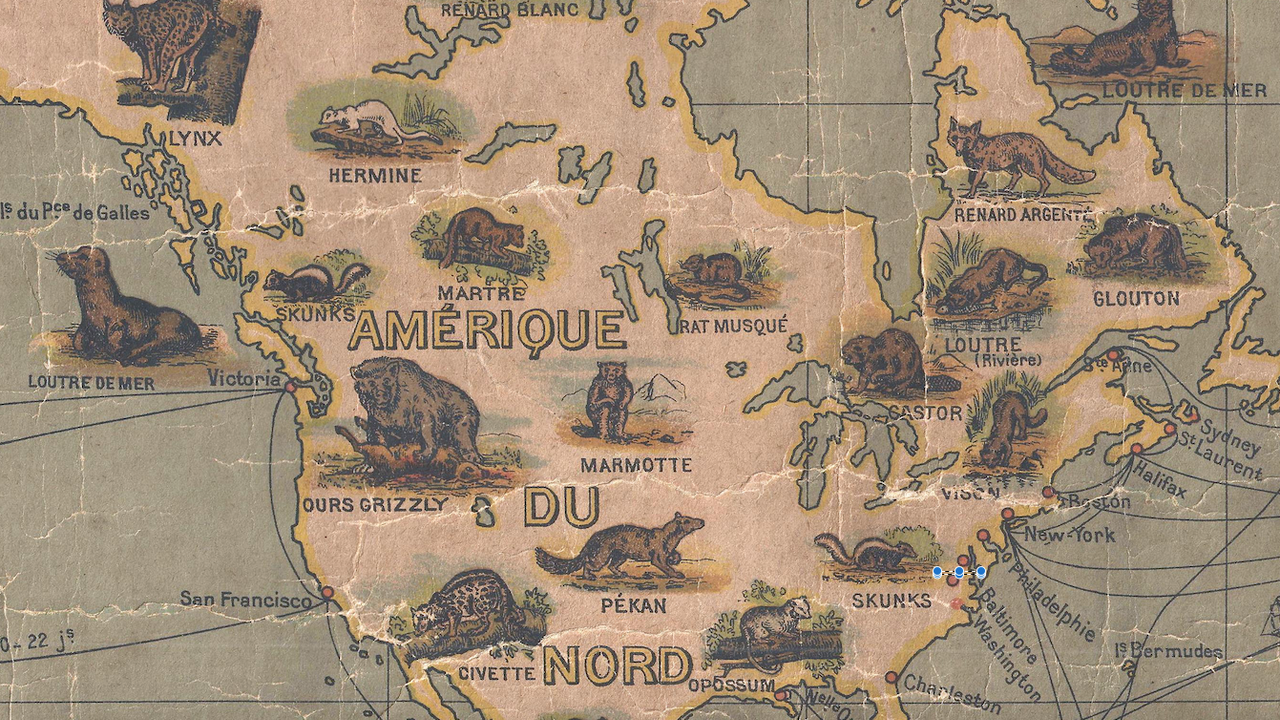

A glance at the sketches on the map reveals the silky sable (zibeline) in Russia, foxes (renard) and wolves (loup) parading across Europe, and the chinchilla and nutria or coypu (ragondin) in South America. The map also includes shipping routes, so potential buyers could easily see that Hamburg was linked with Rio de Janeiro, close to where otters could be found.

The surging popularity of fur in the late 19th and early 20th centuries tracks with the growing influence of Russia and the powerful, often-chilly folks who called it home, explains Hays. The czar (frequently wrapped snugly in pelts) visited Paris in 1896, and the Ballet Russes soon soared to international fame, too. When Russia aligned with Britain and France in World War I, Hays says, fur was close to the epicenter of new fashion trends. Coats lined with coarse, shaggy goat and raccoon fur added a layer of insulation to jackets when passengers went “motoring,” Hays says. (Furs kept soldiers warm during the war, too.)

At the time, Byrd says, fur was accessible to shoppers with a range of budgets. The 1918 Sears catalog peddled a child’s squirrel scarf-and-muff set for $9.95, and asked less for items made from goat hair. Rabbit fur—also known as “coney”—was another option for fur fanciers with tighter purse strings, and was sometimes gussied up to stand in for pricier varieties, advertised as “imitation ermine” or even “imitation tiger.” Squirrel, skunk, and muskrat would have been used for inexpensive or mid-range clothes purchased straight off the rack, Hays says.

On the higher end, there were $50 beaver muffs and capes, peddled to debutantes in the pages of Vogue. Since couturiers were also getting in on the action, women could opt for dresses trimmed with pelts. Hudson Bay hawked seal coats that were true luxury items, with a full-length version running $250 (more than $5,000 in 2018 dollars). Shoppers with money to burn—people with “extreme wealth,” Byrd says—could spring for a wrap made entirely from Russian sable. Meanwhile, “‘exotic’ furs [such as] tiger, leopard, and lion were used primarily for interior decoration, like rugs,” Hays says.

Furriers set out to convince shoppers that the coats and accessories were not just useful for keeping warm, but worthy of investment, even at the cost of a bit of scrimping and saving. As World War I drew to a close, they pitched prospective buyers on the idea that furs were long-lasting, functional, warm, and durable, and that you could always get a coat refashioned to stay with the style of the times, Byrd says—say, by cuffing the sleeve or shortening the hem. This public relations effort sometimes involved mapping the whole world, one mammal at a time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook