How the Library of Congress Unrolled a 2,000-Year-Old Buddhist Scroll

“It was the most fragile object we have ever encountered.”

It’s not easy being a 2,000-year-old Buddhist scroll. A slight gust of wind, a particularly humid day, or even a simple exhalation could cause the scroll to crack or crumble into pieces. To unroll a scroll this old is almost unthinkable—but recently, conservators at the Library of Congress found themselves with no other option. They wanted to read the words scrawled inside the Gandhara scroll.

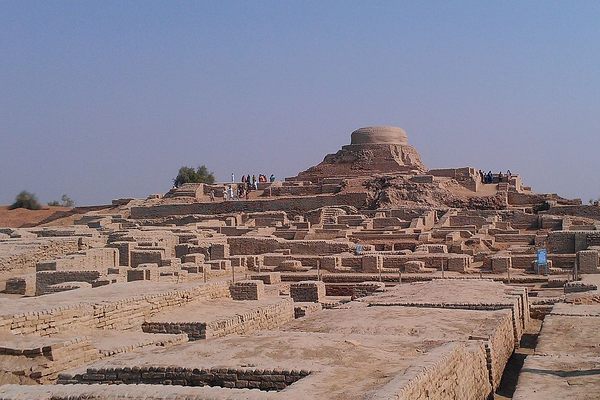

Before the scroll came to the library, it was buried for 2,000 years in a clay jar in a Buddhist stupa, or dome-shaped shrine, in the ancient region of Gandhara, now the Peshawar Valley in northern Afghanistan and Pakistan. The high-altitude, arid climate kept it from crumbling until it was excavated in the 1990s. In 2005, conservators received the scroll in a Parker Pen box on a bed of cotton. “It was the most fragile object we have ever encountered,” Holly Krueger, a retired paper conservator at the library, writes in an email. A year passed before the conservators felt ready to unfurl the scroll without destroying it completely.

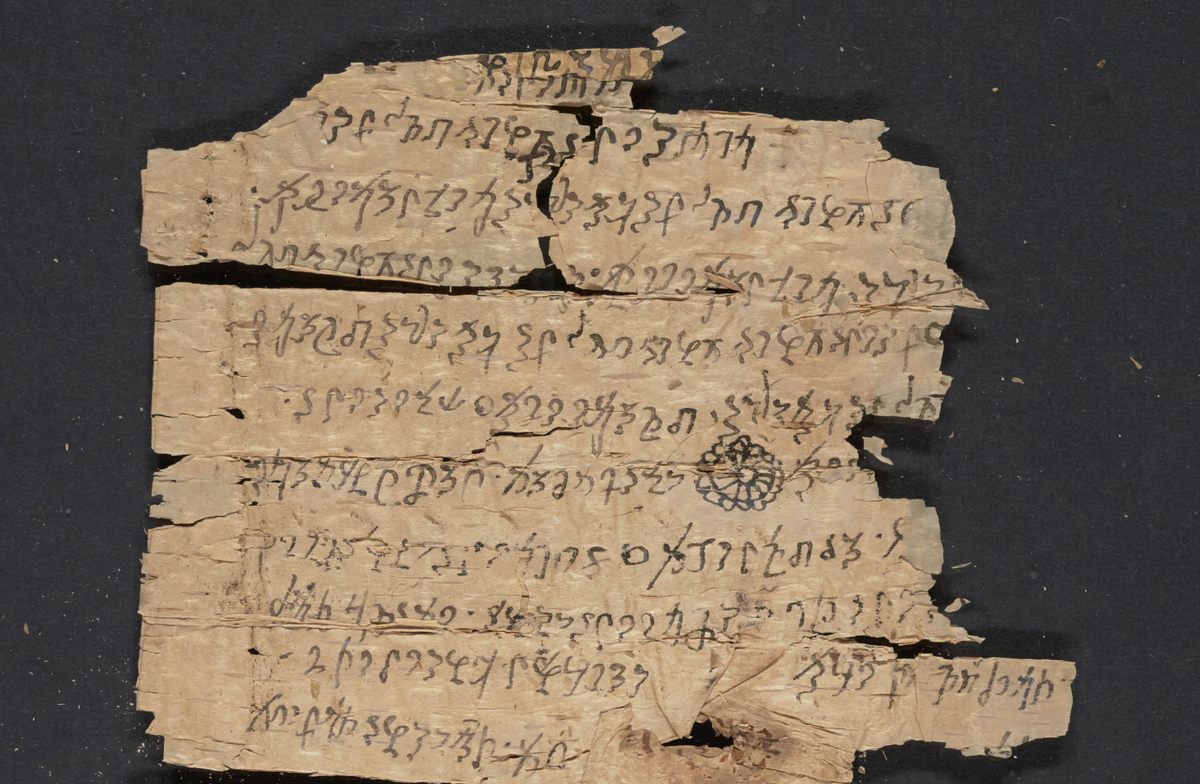

The scroll, which was radiocarbon dated to the first century B.C., is one of a handful of surviving early Buddhist manuscripts from Gandhara, according to Jonathan Loar, a South Asia specialist at the library. Gandhara, situated on the Silk Road, served as a gateway to India, and the region’s monks are credited with spreading Buddhism into Iran and China, Krueger writes in a 2008 paper in The Book and Paper Group Annual. It was written in Gandhari, a language related to Sanskrit, on birch bark, an ancient writing material that consists of thin layers held together with a natural glue—almost like ancient phyllo pastry. “As it ages, this glue breaks down, leaving the layers extremely vulnerable to shattering with the slightest disturbance,” Krueger says, adding that a scroll this unstable could have only survived in a jar.

Krueger consulted conservators at the British Library, who had successfully unrolled 30 scrolls, for their input. Without any ancient, coiled birch bark laying around for a trial run, she practiced on a baked cigar roll, teasing apart its wafer-thin layers with bamboo spatulas. “It was not as fragile as the scroll proved to be,” Krueger says. A few days before the unrolling, the conservators placed the scroll in a specially constructed, humidified chamber, which softened the birch bark so it would not break upon contact.

The actual unrolling happened in June, 2006, on a Saturday, to reduce the risk of air currents created by coworkers and better control the humidity and temperature of the library’s paper lab. Krueger was present with only two others: Yasmeen Khan, a senior rare book conservator at the library, and Mark Barnard, the chief conservator at the British Library. “One cannot underestimate the nerves of steel required for such a project,” Krueger says. “We had only one chance for success.”

Krueger and Barnard removed the scroll from its moist chamber and placed it on top of a pane of borosilicate glass. One turn at a time, using bamboo spatulas, they unfurled the birch bark, placing small glass weights on newly flat sections. Each fresh turn revealed new fragments, which the conservators weighed down to preserve their place in the text. If the scroll seemed on the verge of cracking, a conservator would mist the air with a preservation pencil.

It was a dramatic and silent affair: Everyone took shallow, controlled breaths. One misplaced exhale could scatter the scroll shards and render something translatable into something lost. “I was doing the photography and informed the conservators whenever I was going to move so that they would be prepared for air movement and change,” Khan writes in an email. When the whole thing was laid flat, Krueger and Barnard removed the glass weights and laid a second pane of glass on the whole revealed scroll, pushing down tiny pieces that popped up with the bamboo sticks.

Finally translated, the final scroll has no title, beginning, or end, but it does retain around 75 to 80 percent of the original text—one of the better-preserved Gandharan scrolls in existence, Loar says. It tells the story of 15 seekers of enlightenment who came before and after Siddhārtha Gautama, the sage living in the 5th or 6th century B.C. who became known as the Buddha. “Repeating these names—verbally, mentally, and or in writing—is a powerful practice,” Loar says, adding that it functioned as a meditative exercise.

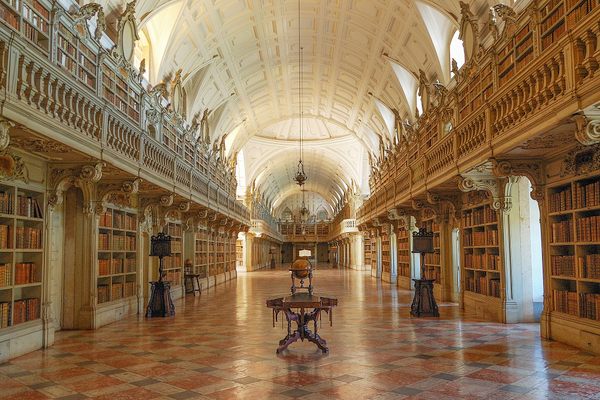

Too fragile for public display, the scroll has been reburied—this time in a box within the archives of the library. There’s also a drawer that holds all the tiny bits of dust that sprung from the scroll during the unrolling. Conservators now transport it around the library on a cart with vibration dampening to ease its journey, Krueger says. But this past summer, the conservators digitized the entire scroll, making it surprisingly easy to read a millennia-old account of the lives of buddhas—that is, if you read Gandhari.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook