Scientists Want You to Photograph This Curious, Enigmatic Giant

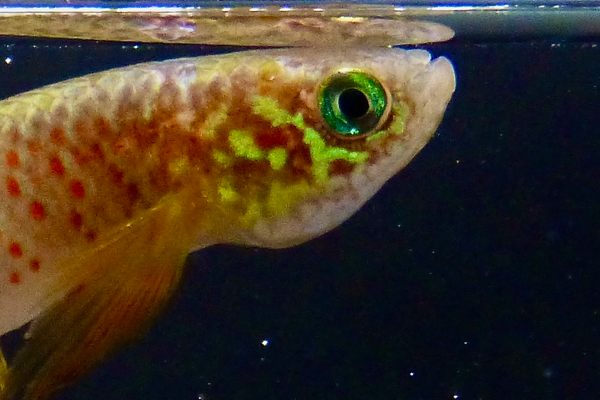

Keep an eye out for the giant sea bass’s spots.

For a goggled human, coming face to face with a giant sea bass can be a little unsettling. Gray and gargantuan—sometimes growing more than seven feet long and topping out around 550 pounds—the husky Stereolepis gigas are “the rhinos of the kelp forest,” says Molly Morse, a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Initiative at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The heftiest marine bony fish close to California’s shore, the aptly named creature is prone to spooking divers, Morse says. “Imagine being underwater, where your senses are already on overdrive because you’re experiencing all this stuff you’re not used to,” she says. If the hulking fish starts to swim into your peripheral vision, “Initially, you might assume, ‘Oh, my gosh—it’s a great white shark, I’m going to die.’”

But the giant sea bass isn’t out for human blood: It’s usually unusually affable, Morse says, and curious about human antics. Unfortunately, that gentleness once led fishers to identify it as an easy target and drastically hobble the population, which is known to swim only along the coasts of California and Mexico.

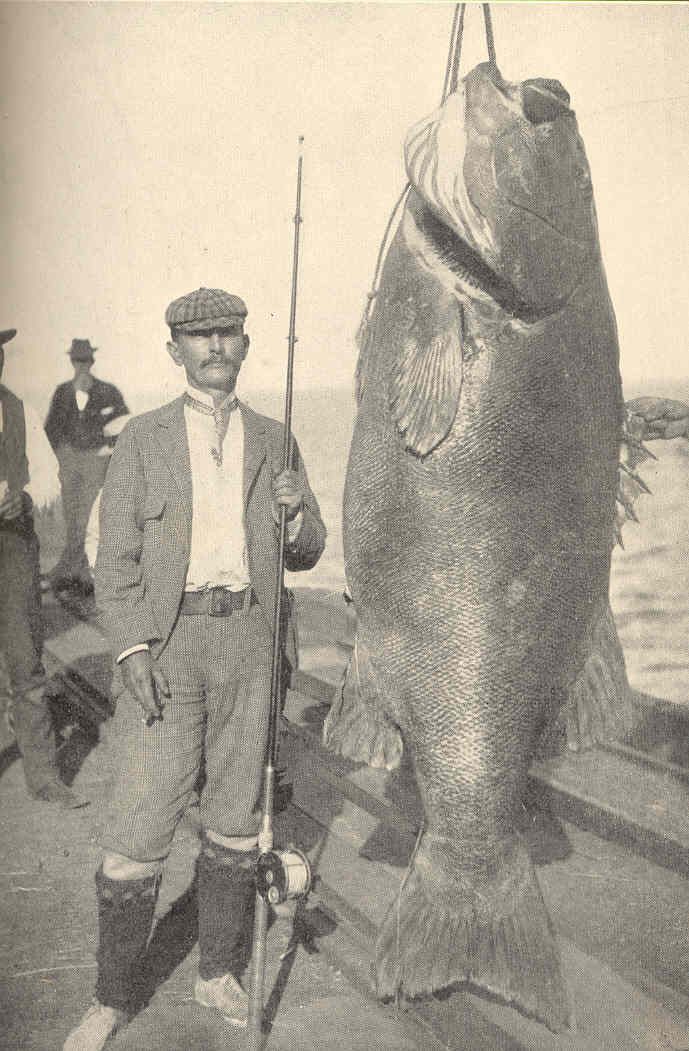

Commercial fishing of the giant sea bass peaked in the 1930s, Morse says, and recreational fishers really went to town in the 1960s. According to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, fishing contributed to the population shrinking by as much as 95 percent, and it still hasn’t fully rebounded: The giant sea bass is listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), and has been legally protected in California since the 1980s.

“The assumption is that if we have laws in place, and they’re being followed, [the fish] should be able to reproduce,” Morse says. Scientists speculate that the species is probably bouncing back, she adds, but because population estimates are still opaque, “there’s not a lot of evidence to demonstrate that scientifically.” And even if their numbers are creeping back up, the fish face other problems.

“We don’t know how many giant sea bass are actually out there,” writes Chris Chabot, a biologist at California State University, Northridge, in an email. Based on his research—some of which was published in Fisheries Research in 2015—“the amount of genetic diversity existing within the current population of giant sea bass is VERY low,” he says.

To help give the big fish a boost in the wild, divers are plopping several hundred giant sea bass reared by the Aquarium of the Pacific and the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium into the ocean. At the beginning of March 2020, close to 200 babies from the Cabrillo aquarium began to settle into the waters of Santa Monica Bay; the Aquarium of the Pacific’s brood will be next.

To gather scientific evidence about how these and other members of the species are faring out there, a citizen-science project is tapping recreational divers in California to send in photos of the fish they encounter in the watery neighborhoods they swim through.

The aquariums lucked into a windfall of eggs from Cal State Northridge, where researchers studying giant sea bass last spring found themselves with more eggs than they knew what to do with.

Raising young marine fish (also known as saltwater fish) in captivity can be tricky, partly because they need to chow down on so many different types of crustaceans and fish as they grow. That means aquariums have to stock and care for those creatures too. Newly hatched giant sea bass feed on rotifers, a type of zooplankton, “but that only lasts a week or a couple of weeks before they’ve grown enough to need a larger-sized plankton, and then a few weeks later they’re on to a different one,” says Sandy Trautwein, vice president of husbandry at the Aquarium of the Pacific, where she oversees the conservation and research program for giant sea bass and other creatures.

It’s hard to quantify exactly how much food the giant sea bass gobble as they grow, Trautwein adds—“but it’s a lot.” To keep a fully stocked buffet for the finned residents, the Aquarium of the Pacific has 15 or 20 tanks of various sizes dedicated solely to raising “live foods”—that is, nurturing creatures for other creatures to eat. Captive-raised giant sea bass may chow down on everything from squid to sardines to clams, and they go bananas for shrimp.

“Shrimp is always served last because it’s like ice cream to baby giant sea bass,” Andres Carrillo of the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium told the Los Angeles Times. “They’re like little kids: If you offer giant sea bass shrimp first, they won’t eat anything else.”

The Aquarium of the Pacific has been able to breed and raise giant sea bass in captivity in part because it was able to simulate the natural world, Trautwein says. Sunlight pours in through skylights, and darkness does too, meaning that the fish are exposed to the same photoperiods that their relatives experience in the wild.

The Cabrillo aquarium had additional success by slightly tweaking the water temperature, Trautwein says. The Aquarium of the Pacific had kept the water in the bracingly pleasant high-50s Fahrenheit; the Cabrillo aquarium bumped that up by just a few degrees. Researchers there found that the sweet spot for giant sea bass babies is in the low- to mid-60s. The fact that nudging the temperature so slightly made a difference portends big changes for marine life in warming waters, Trautwein says: “Just a few degrees of warming or cooling can significantly affect the life cycle.”

The newly released fish will have two main items on their to-do list, Morse says: “Avoid getting eaten, and find something to eat.” Young giant sea bass are known to roam sandy bottoms, where they feast on mysid shrimp. When they grow up, they flock to kelp forests and rocky reefs—including the areas around Casino Point, on Catalina Island, and the artificial reef at Hermosa Beach—and hunt for larger prey. Some descend into the cold depths more than 160 feet below the surface, where they’ve been spotted by baited underwater cameras beaming a small halo of light into the inkinesss. What the fish do between youth and adulthood, though, is murky. Trautwein calls it “the missing link.”

To fill in the blanks about life cycle and migration patterns, Morse’s team at the Spotting Giant Sea Bass project calls on divers to share observations of the fish they see—and specifically of the spots that speckle them.

Individual giant sea bass have unique spot patterns—get a clear photograph of them, and you should be able to identify one that is sighted again later. Morse’s team collects these photos and runs them through an algorithm that she says NASA once used to detect patterns in constellations.

If the researchers get lucky, a bass will also sport a scar, a clipped fin, or another distinctive marking. Those dings and dents are helpful because the spots aren’t always on display: The fish “have the ability to turn them on and off,” Morse says, though researchers aren’t sure why. Sometimes the spots appear to be absent on a fish that was once spangled. “We will get photos of the same fish where it has very clear spot patterns, easy for us to recognize, and get an image of the same fish—maybe with identifying scar or something—and it doesn’t have any spots at all.”

Sometimes divers, pressed for time or luck or just distractedly excited, will photograph only one side of a fish. Since the two sides may hold different spot patterns, a single fish can be mistaken for two. The aquarium fish were photographed before their big journey to the sea, and Morse’s team has those images ready to go for a quick comparison if they’re spotted again.

Because so many observations of giant sea bass come from recreational divers, who tend to swim in the summer and fall, scientists are also keen to know what the fish do during the rest of the year. Reported sightings and photographs drop off significantly in the winter and spring, Morse says, so traditional tagging methods and more baited cameras could help scientists figure out whether the fish are up to their same old routines in their same old swimming grounds, or whether “we weren’t seeing any giant sea bass because there weren’t any giant sea bass,” Morse says.

If you see any swimming off the coast of California—little or really, truly giant—give them some room to roam. But, if you can, snap a picture of their spots. Morse would love to see it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook