The Renaissance Painter Who Made Fantastical Portraits From Food

Giuseppe Arcimboldo painted surreal art unlike any of his contemporaries.

Looked at one way, Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s “The Vegetable Gardener” (1587-1590) looks like a black bowl overflowing with root vegetables, greens, and one huge onion.

But flipped, the painting become something else entirely. The onion has become a plump cheek, while the huge parsnip is a bulbous nose. The bowl is now a hat, perched on what is now obviously a smiling face.

Many of Arcimboldo’s peers in the 16th century were painting portraits or still lifes, but Arcimboldo had the bright idea of combining the two, creating an instantly recognizable style that inspired 20th century Surrealists.

Nothing about Arcimboldo’s early career as a stained glass and fresco designer suggested that he’d develop this distinctive style. It wasn’t until he landed a cushy post as court portraitist to Emperor Maximilian II of the Holy Roman Empire in 1562 that he started painting, along with typical portraits of court members, his series of composite faces. Often set against pitch-black backgrounds, each composite face is made of animals, objects, or, most famously, food.

His royal patrons had a taste for the odd and unusual. Emperor Maximilian II and his son Rudolf II were reportedly delighted by Arcimboldo’s style. They kept him busy with commissions, including paintings and drawings that documented the imperial family’s collection of artistic works and natural curiosities. These Wunderkammers—compilations of oddities owned by the royal and rich—were the predecessors to museums, and they often focused on novel objects (taxidermied animals, preserved plants, cultural artifacts) brought back by European explorers. Organizing and displaying wild and wonderful objects not only fed the Renaissance appetite for the esoteric, but also exerted power over and made sense of a changing world.

Undoubtedly influenced by the imperial collections, many of Arcimboldo’s food faces featured ingredients from the Americas. His 1563 series of paintings depicts the four seasons as male figures, from young Spring to geriatric Winter, using seasonal produce. Along with Spring’s literally rosy cheeks and and Winter’s lemons, newer additions to Europe’s gardens appear. Summer’s ear is an an ear of corn, while Autumn’s head is a white pumpkin. Both were relatively recent arrivals from the Americas.

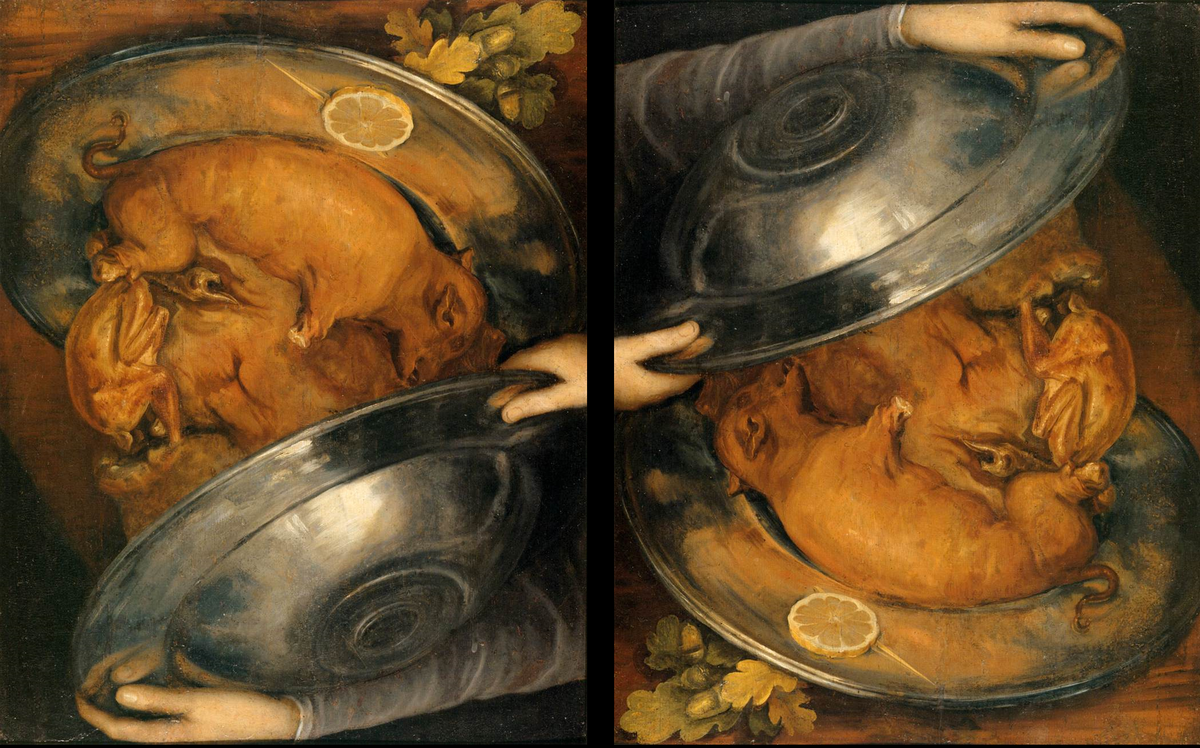

Arcimboldo’s whimsical faces sometimes had real-world models, the most famous example being his 1590 painting of Rudolf as Vertumnus, the Roman god of the four seasons. Arcimboldo painted figures made of books, wine-making supplies, and, most eerily, meat. In a style similar to “The Vegetable Gardener,” “The Cook” (1570) is a reversible painting. When displayed on one end, it’s a haphazard pile of roasted piglet and chicken. Flipped, it’s a grotesque face, with a small bird as a deformed-looking nose and a pig’s tail as a curl of hair. The silver serving platter becomes a broad hat, decorated with greens and a slice of lemon. At one recent exhibition of Arcimboldo’s work, mirrors installed beneath the painting showed visitors the flipped version.

Though Arcimboldo was renowned during his life, his fame didn’t last long after his death in 1593. But his work gained prominence in the early 20th century, as his flair for the surreal and allegorical inspired a generation of artists, including Man Ray and Salvador Dalí.

Like the plants he portrayed, a long dormancy didn’t mean Arcimboldo’s whimsical style of painting was dead. It just wasn’t yet back in season.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook