How a Dublin Pub Became a Haunt for Gravediggers and Ghosts Alike

The watering hole sits next to a cemetery and has stories to match.

Tales of spirits, the afterlife, and the paranormal are often passed down from generation to generation. Through recounting these stories, myth can get entangled in fact and vice versa, and can eventually make up a reality that we’re both eager to hear and take part in. When it comes to John Kavanagh—better known nowadays by its nickname, The Gravediggers Pub—it can be tough to separate facts from stories mired in myth. They’ve both been told so many times in the pub’s near 200 years of existence that they’ve become integral parts of the narrative, and continue to draw people in for a drink.

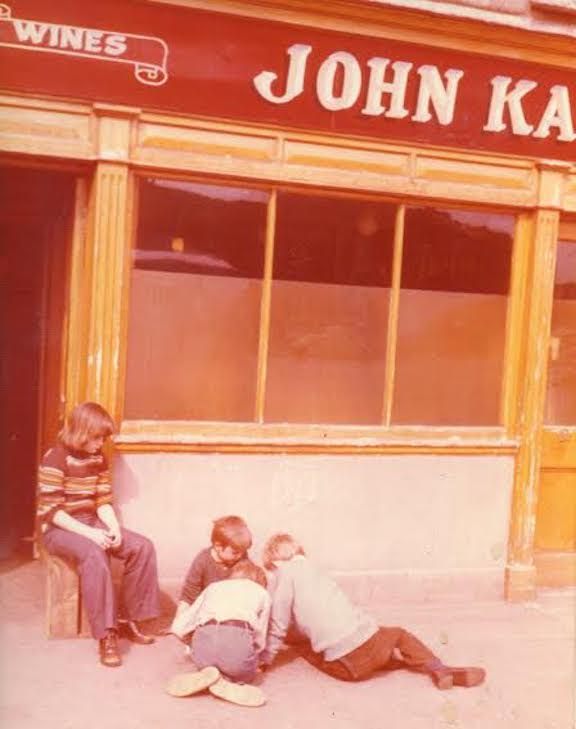

John Kavanagh is situated at the southeastern tip of Glasnevin Cemetery’s wall, next to where the main entrance was until the 1970s. It opened in north Dublin in 1833, just a year after the cemetery opened to Irish citizens of all faiths. The graveyard was the first of its kind, opening after there had been a public outcry over discrimination against Catholics. A political petition then passed to unite Catholics and Protestants in death, if not in life. This also means that the locale, as well as the pub situated next to it, might carry ghost stories from all sectors of early 19th-century Dublin.

“This isn’t a wealthy Victorian bar of stained glass and gilt mirrors,” as a promotional pamphlet for the pub put it. “This was and is a workingman’s bar of straight-talking and creamy pints, a generational mix of customers from all walks of life trading tales.” The neighborhood watering hole was gifted to Kavanagh by his father-in-law (a hotelier who had recently purchased the building) after he married Suzanne O’Neill. They drew in much of their business from funerals, helping to comfort grieving families for decades. And when they dispersed, it was the gravediggers who’d finish off their shifts with a pint.

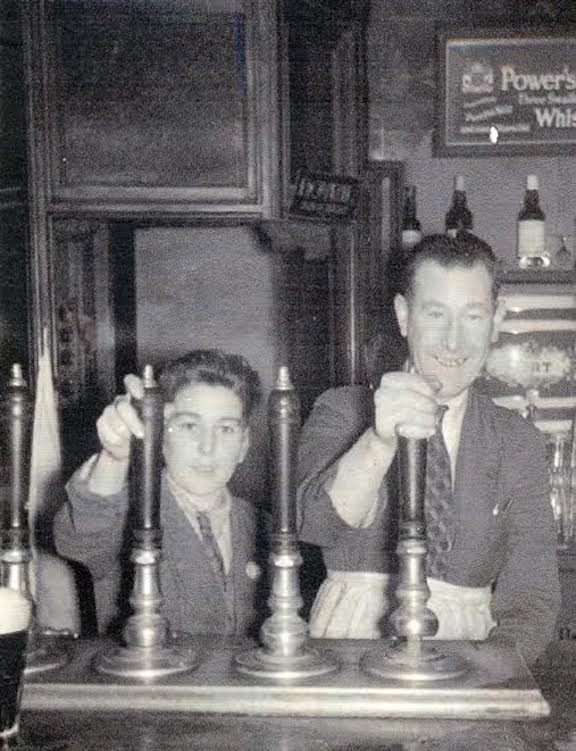

The one-room bar featured low ceilings, dark wood, and a game of ring board. There was—and still is, though only for show—a sectioned-off area at the top of the bar where women could drink separately from the men. It’s always been no-frills at John Kavanagh: They’ve never owned a phone nor a sound system. In the 1980s, when Eugene Kavanagh (John’s great-great-great grandson) was owner for a decade already, he built a lounge area about triple the size of the original bar to help business during an economic downturn. In the early aughts, Ciarán Kavanagh—Eugene’s son, and the bar’s head chef these days—came back from his culinary studies in Italy and began concocting both original and traditional dishes such as coddle and Irish spring rolls. Today, Kathleen Kavanagh, his mother, runs the business, and day-to-day operations are managed by her daughter, Anne Kavanagh, and sons Anthony and Niall Kavanagh.

Recently, Gravediggers Pub won the award for the Best Community Pub in Ireland by Irish Hospitality Global. It’s not hard to see why. The ale-splashed floors and nicotine-stained walls are as authentic as one can get in an Irish pub, and the family behind the original bar counters (moved back a few feet about half a century ago to create extra drinking space) is made up of the seventh-generation of Kavanaghs. The eighth generation isn’t far behind, helping out in the lounge after school serving their uncle’s famous fare.

In 1973, when Eugene took over for his father, the pub hosted almost exclusively locals—and that included gravediggers. The cemetery workers were known to neck a pint or two after a long days’ work of digging graves. Though the pub only adopted the nickname of “Gravediggers” within the last two decades, the gravediggers’ proximity both earned the pub its macabre moniker and the story that their pints used to come to them via a hole in the cemetery wall. “It’s one of those things we can’t really confirm or deny,” says Ciarán. “No one is alive to deny it, but I heard that people put their hands through the wall to get their pints. None of my relations ever told me this, but I’d heard it talked about.”

Ciarán can attest to gravediggers knocking on the wall for their pints, though, given that the pub’s back wall brushes up right against the cemetery’s. Glasnevin’s stone wall currently stands where a storage building once did, for about 50 years in the early 20th century. The building, which caught on fire and was never replaced, had the wall that gravediggers would knock on with their shovels, their boots, a stone—“hopefully not a skull,” smirks Ciarán—for their beer. “My great-grandfather and my grandfather would go outside and put a drink through the [cemetery wall] railings,” he says.

According to historian Ciarán Wallace—who edited the book Grave Matters: Death and Dying in Dublin, 1500 to the Present along with Lisa Maria Griffith—that would have been in breach of alcohol licensing laws. But he does recount that same old story of gravediggers knocking on the wall for their pint to be ready when they came through the gate. “To be honest, this seems unlikely and unnecessary as the wall and gate and pub door are only 10 paces apart,” he says.

But Wallace, who happened to have briefly worked at the pub in the late 1970s, seems much more convinced of the ghosts than the gravediggers’ shenanigans. He has a few stories that he heard recounted countless times as a teenager working nights and weekends, but his favorite is the one with the dog. One evening, as Uncle Jack Kavanagh locked up and counted the days’ till, he let the bad-tempered Alsatian in. This dog was such a grump that he was never allowed inside the pub when customers were around, but he was decent enough with Jack. He probably added some extra protection when counting the money, too.

“[Jack] had to go upstairs for a moment,” says Wallace, “But on returning to the door to the bar he met the dog, hackle raised, growling and backing out of the bar. Jack presumed there were robbers inside, but he saw nobody. He tried to get the dog to attack, but the dog was too scared and would not go inside the bar area. Some unseen thing had terrified a very aggressive dog. Jack locked the internal door, left the money on the counter, and put the dog outside. He went up to bed for an uncomfortable night’s sleep. In the morning, the cash was all there and the dog was happy to be let out the back.”

Anne, the front-of-house manager and Ciarán’s sister, has her own hair-raising ghost story from when she was 17 years old. This happened back when the family lived in a small second-floor flat above the original bar. She was just falling asleep when she saw a young girl with brown curly hair perched at the foot of her bed. “I kept blinking and blinking, and realized quickly that I was still awake,” Anne says. “There she was, in a white night-dress with a frilly collar, puffed up shoulders and long sleeves. She just smiled at me…then she was gone.” There’s no way that apparition was the product of one too many pints, either. “I didn’t drink until I was in my 30s,” she adds. “So there wasn’t any relation to drink or anything.”

The years that Eugene ran the pub, a repeat ghost—the man in tweed—visited. Sometimes, Eugene had to shuffle out stragglers in the wee hours of the night when the bar was closing. On one of these nights, the man in tweed appeared for what would be the first several times. Eugene yelled at the boys to get on back to their homes, when they retorted that it was unfair that the old guy at the other end of the bar got to stay, nursing his Guinness. At first, Eugene just thought the lads were being drunk and silly. He claimed that he knew every pint he’d served that night, especially in the waning last few hours.

“’I’d have served him that pint and I haven’t served anyone a Guinness,’ he’d say,” says Ciarán. “’Look,’ my dad would continue, ‘there’s nobody there.’ And sure enough, no one was. But an empty glass of Guinness sat on the bar. The boys would have described what he looked like—a little pointy beard and a wristwatch with a chain that led to his waistcoat, a real Victorian look.”

Eugene—because of his run-ins with unexplained phenomena—eventually brought in mediums and hosted séances, and even invited some ghost hunters to film there in the early aughts. Regulars have their own tales, some that even involve family members buried in the cemetery next door. And nearly all of the Kavanaghs have a tale about closing up late at night and hearing keys jiggling, or the dog’s hair standing up on end and growls toward seemingly nothing, though Ciarán has never experienced it himself.

“I drink a whiskey and sometimes tequila,” Ciarán says. “But those are the only spirits I’ve seen. You definitely can feel that the generations of my family are here, but to see them you have to be there at the right time. I’ve been standing in the pub and thought, ‘God, my father all the way to my great-grandfather was standing in this very spot doing exactly the same thing I’m doing now.’ And that’s pretty cool and spooky if you ask me.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook