The Family Recipes That Live On in Cemeteries

Around the world, recipe gravestones tell stories of love, grief, and remembrance.

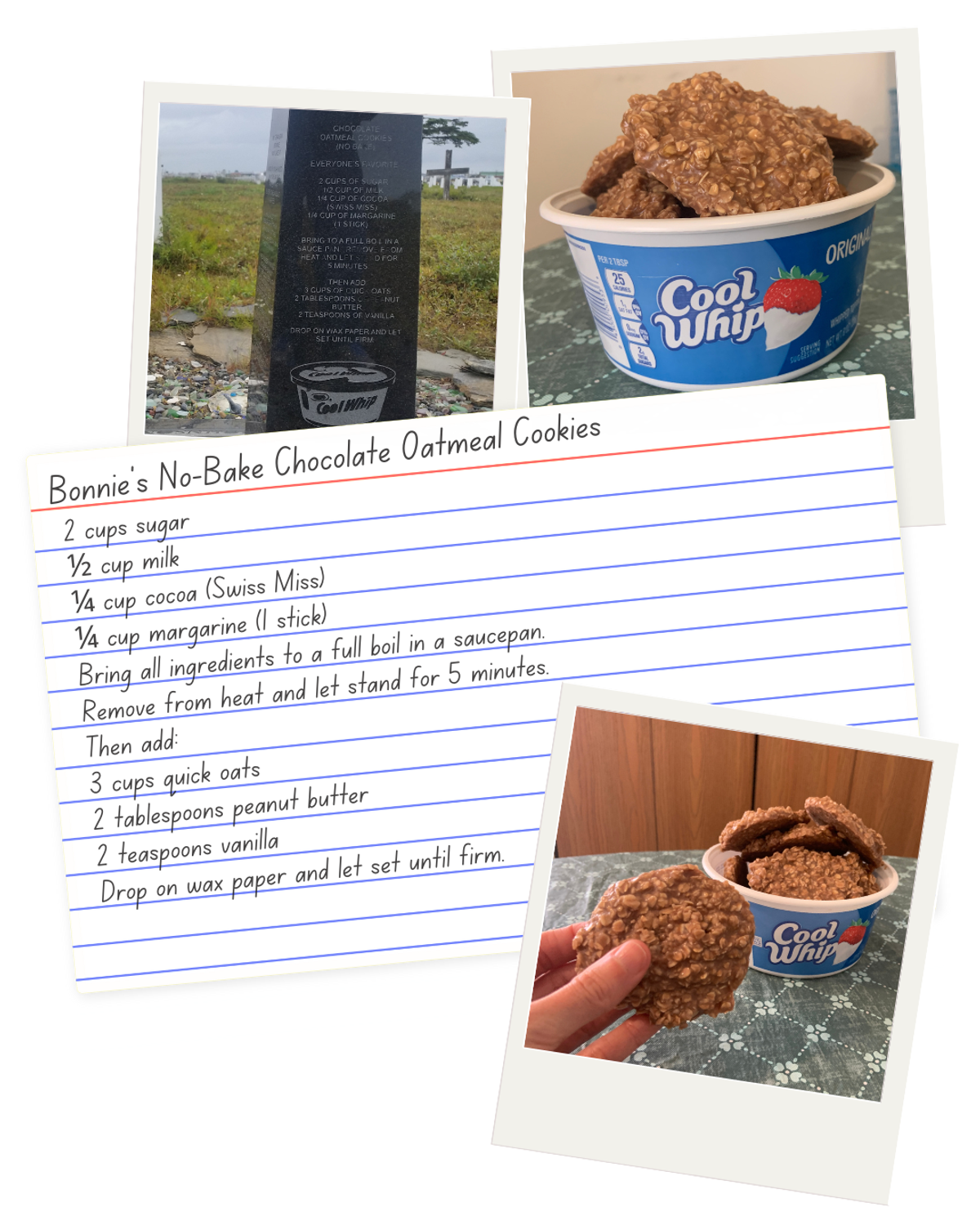

On a clear day at Nome City Cemetery, you can watch planes take off over the Bering Sea. Within the field of white graves, you might also see a small black obelisk that shines brilliantly when it catches the sun. Getting closer, you’ll note an unmistakable symbol engraved near its base. It’s not a cross, nor a Star of David, but a sacred container of sorts in many American households: a tub of Cool Whip.

The grave belongs to Bonnie Johnson, a mother, former flight attendant, and creator of a cookie recipe whose batches always arrived at birthdays, holidays, and school events housed inside empty Cool Whip containers. Anyone looking to make Johnson’s classic no-bake chocolate oatmeal cookies is in luck. Her recipe is also etched into her gravestone.

Johnson’s memorial is not the only one of its kind. There are at least 18 graves around the world inscribed with a cherished family recipe. They stretch across religions, borders, and decades. In Seattle, Washington, a grandmother’s blueberry pie is immortalized on the side of a black bench. On an Israeli kibbutz, a father and professional baker’s famous yeast roll recipe is etched in Hebrew on white stone. In Upstate New York, a mother’s handwritten instructions on cooking chicken soup are carved into pink granite.

A grave is a story told in symbols and shorthand. Some of these messages are straightforward. A death year shared among many cemetery residents might point to a historic epidemic or local disaster. A fraternal order symbol is easily decoded from memory or with a Google search. Messages coded in Cool Whip, two teaspoons of vanilla, and a few cups of oats, however, might be more difficult to discern.

But recipes do tell stories. In her essay, “Claiming a Piece of the Pie: How the Language of Recipes Defines Community,” linguist Colleen Cotter writes that “a recipe can be viewed as a story, a cultural narrative that can be shared and has been constructed by members of a community.” She reflects on her grandmother’s ability to “read a cookbook like a novel” because it “carried elements that fired her imagination, that drew her in, that caused her to reflect on her own behavior (as a cook), and to construct her her identity … in terms that were readily accessible to her and in relation to her peers.”

Can you read a recipe grave like a novel? If so, it’s only fitting to start with the ingredients.

Sugar. Milk. Cocoa. Margarine. Oats. Peanut butter. Vanilla.

In 1957, Bonnie Johnson packed her belongings in a station wagon and drove from Washington State to the territory of Alaska. There, she took a job as a flight attendant, married, saw Alaska become a U.S. state, started working for the Department of Revenue and the DMV, and had four children.

Living on the frontier had its charms: She loved flying around the territory in Cordova Airlines’ DC-3s and even got to see President Dwight Eisenhower attend the parade celebrating Alaska’s gaining statehood in 1959. But there were also drawbacks: Grocery shopping, for instance, was now an errand that needed the precise logistics of a military operation.

“When we were kids, the barge or steamship came and you had most of your bulk groceries in there,” her son, Doug Johnson, remembers. “You go to the store for your daily stuff, but things that cost a lot of money, you had to stockpile.” Since barges typically didn’t come during the winter, families had to stretch those stockpiles across several months.

Johnson’s cookie recipe is a snapshot of a mother making the most of this constrained pantry: Other than milk, all of its ingredients could be stored for months. The no-bake recipe was also perfect for whipping up a batch at a moment’s notice: “She had three boys who ate her out of house and home,” Doug laughs. “I remember from the second grade on, she was making cookies for school projects, birthdays, Valentine’s Day, Thanksgiving—whatever the occasion was, she’d bring them.”

“She lived through so many times where saving things was really important,” Doug’s wife, Robin, adds. This no-waste approach not only applied to her cooking, but her signature serving dish. When Robin and Doug moved her out of her longtime home toward the end of her life, they found stacks of empty Cool Whip containers.

After Bonnie died in 2007, her children erected an obelisk with different pieces of her life story carved into each side: a poem by her granddaughter, a plane to denote her high-flying years, a five-pointed star (to represent her years as “grand poobah at the [local] Order of the Eastern Star,” Doug says), a Cool Whip tub, and her cookie recipe. They often gather around the monument, scatter at its feet new pieces of beach glass they’ve gathered along the shore, and remember a mother who made the most of what she had.

Even though access to fresh groceries has improved in Nome, Doug and Robin still swear by Bonnie’s cookies. “She must have customized the recipe because it’s not like any other no-bake cookie I’ve ever had,” Robin says. “They’re really good.”

It’s easy to dismiss a recipe grave as mere novelty. But memorials celebrating an individual’s culinary achievements are not a new development. The most notable of these might be the tomb of Eurysaces, a Roman baker who built a memorial for himself sometime between 50 and 20 BC. The grand structure’s frieze offers a remarkable glimpse into the ancient art of breadmaking, featuring figures grinding grain, kneading dough, and baking loaves in domed ovens. If the detailed design wasn’t enough to demonstrate Eurysaces’s success, the inscription brags, “This is the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, it’s obvious!”

Such historic tributes tend to focus on the public, professional accomplishments of men. But modern recipe graves, which start appearing around the 1990s, largely celebrate the achievements of women within a family.

In the United States, where most recipe graves are located, the epitaphs are part of a recent progression toward showcasing personal identities and interests in headstone designs. Keith Eggener, an art and architecture professor at the University of Oregon and author of Cemeteries, notes that this is a marked shift from the American custom of linking the deceased to a larger group, such as a fraternal order or religion, on headstones from the 18th through early 20th centuries.

“In these earlier stones, you’re showing not so much your individual identity, but your membership in a broader community of worthy citizens,” Eggener says. As membership in organized religions and fraternal orders have declined, however, new depictions of worth have emerged.

“A grave shows what is important to you,” says Candi Cann, a religious studies professor at Baylor University who writes about the intersection of food and death traditions. According to Cann, recipes have come to serve as shorthand for love and nurturing. “If a recipe is a symbol of who you are, that means that you cared about having people over and feeding them and taking care of them.” In fact, Cann opens the anthology she edited, Dying to Eat: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Food, Death, and the Afterlife, with a dedication to her late mother: “My recipe box is a shrine to you and to your memory.”

Recipe gravestones also show a change in how women are memorialized. “You think about so many women when they were buried, [their gravestones] would just be like ‘Mrs. John Smith,’ and her name would be erased,” adds Cann. “But with a recipe epitaph, “she’s immortalized through the food. That’s one place where her name matters.”

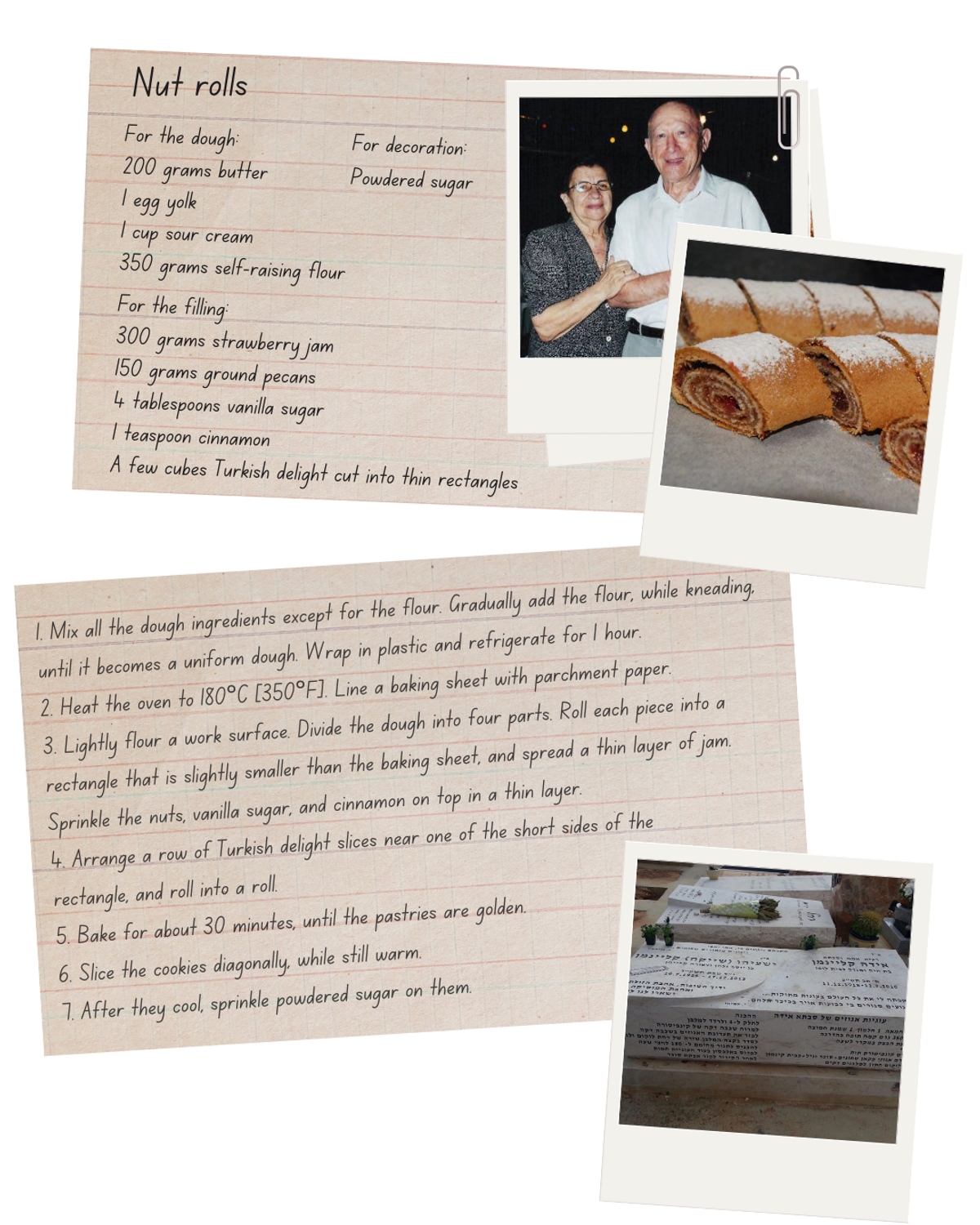

In Rehovot, Israel, Ida Kleinman’s name will live on through her nut rolls. When visiting her grave, which bears the sweet recipe, her son, Yossi Kleinman, likes to hover nearby. Sometimes, a passerby might take note of the inscription and grin. Another might even take out a sheet of paper and write it down.

“This is what we wanted it to be,” he says. “People walk by and smile a little.”

Yossi designed the grave himself, working with a stonecutter to execute his vision: a flat-topped, rectangular tombstone etched in Hebrew with his parents’ biographical information on top and his mother’s nut roll recipe on its front. He and his sister decided that the recipe was the perfect tribute to their mother, who always provided comfort. When Ida and Isaiah Kleinman emigrated to Israel in the late 1940s, they didn’t have much. Ida had escaped poverty in Romania, while Isaiah was a Polish Holocaust survivor who had endured nine separate concentration camps. But they built a new life in Rehovot, elevating their modest means with love and care.

“Even though we were not rich, they always took care of us,” Yossi remembers. “My mother was a very strict and meticulous woman. She had good hands. We used to say she had ‘golden hands,’ actually. She could mend any torn garment and make these perfect cookies.”

Ida’s nut rolls were packed with sweetness: strawberry jam, ground pecans, vanilla sugar, cinnamon, and chunks of Turkish delight that were rolled up in dough, baked, and sliced to pieces. While even a misshapen morsel would be delicious, Ida sought to make every roll and every swirl of filling perfect. One day, Yossi came home to find his mother rolling dough and his father standing nearby with a ruler, measuring to ensure that each piece was exactly the same size. The work paid off: Ida’s nut rolls became legendary in her community, a staple at birthdays, holidays, and office parties.

“The food that you make as a family tells your family story and your family history,” says Cann. When you see a recipe on a grave, “You can start to imagine the get-together … it definitely creates this imaginary space more than just the average headstone. Pictures don’t even tell a story in the same way that a recipe does.”

For Richard Dawson, that story is one of his family gathered in their Brooklyn kitchen for the holidays, with his mother baking cookies and his aunt making kingfish and cou cou, a specialty of their ancestral home in Barbados. He remembers burning his fingers alongside his sister and cousin as they snagged cookies right out of the oven when his mother’s back was turned.

That cookie recipe is inscribed on his mother’s gravestone, a tall slab of rose granite topped with a sculpture of an open book. Instead of prayers or poetry, the pages reveal Naomi Odessa Miller-Dawson’s ingredients for spritz cookies. Richard knows that visitors to Green-Wood Cemetery may see the short ingredient list—butter, sugar, vanilla, egg, flour, baking powder, and salt—and wonder what makes such a simple recipe worth immortalizing.

“It’s more than just the recipe,” he says. “People are intrigued by seeing a recipe and wondering why it’s there, thinking, She must be a chef, or something like that,” Richard says. (Naomi wasn’t a professional chef; she was a postal worker.) “But it was just an acknowledgment of the love that went into her baking.”

Whether or not it’s etched in stone, every recipe is a roadmap to recreating a memory, aroma by aroma, flavor by flavor. In many cultures, the act of cooking itself can serve as a ritual of remembrance. In Kyrgyzstan, when women make borsok, a fried bread that honors the dead, the sizzling oil’s smoke is thought to carry prayers to the spirit world above. In Greece, families pray and reflect on the deceased as they make koliva—a mixture of wheat berries, roasted nuts, dried fruit, and honey—that’s given to funeral attendees. In Mexico, the living make pan de muerto and tamales to offer to their relatives’ spirits every Día de los Muertos.

In one household in Cascade, Iowa, a family bakes cookies.

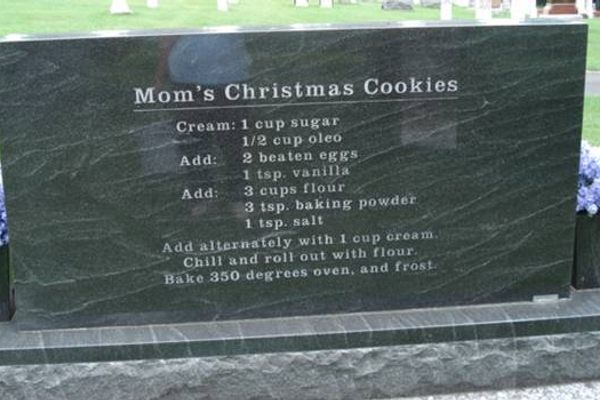

Every Christmas Day, young Maxine Menster awoke to the smell of freshly-baked treats. Among the tinsel and ornaments, cookies in the shapes of galloping horses dangled from the Christmas tree.

“Mom would talk about how it was such a wonderful thing to wake up Christmas morning and have those cookies on the tree,” says Jane Menster, Maxine’s daughter.

When Maxine started her own family, she continued the tradition, even using her grandparents’ 19th-century cookie cutters. One year, Jane remembers three generations crowded into the kitchen to make a big batch: Her mother rolled the dough and baked, her grandparents frosted and sprinkled sugar on them, and she frosted a few herself at a small card table. “It seemed like there were thousands of cookies,” she says.

The Menster family grew up and grew old around these cookie-laden tables. Jane recalls her now-adult nephew’s childhood penchant for stealing a few early bites. “I can still see those little hands reaching up on the table,” she laughs. But the tradition also marked a more somber outcome of the passage of time, as loved ones gradually disappeared from the kitchen.

When Maxine died in 1994, her family not only continued making the cookies, but they inscribed the recipe for “Mom’s Christmas Cookies” into her gravestone. For Jane, the sweet memories soothe her when she feels the pangs of grief. Decades later, when I talk to her over the phone, there is still pain in her voice when she speaks about her mother.

“You know, your parents are gone, you’ve got this recipe on there,” she says, pausing to take a deep breath. “And it’s … it’s okay because it’s the correct procession of time, you know? There’s nothing sad connected to those cookies at all. Making them keeps those happy memories alive.”

Remembering the dead through cooking is one thing. But can a recipe actually help the bereaved to heal? The people behind the Culinary Grief Therapy program in Illinois think so. Created by Heather Nickrand, a social worker and bereavement coordinator, the program blends cooking with group therapy for people coping with the loss of a loved one. For widowers, it’s often learning to cook for themselves for the first time; for older women, it might be tackling the backyard grill or adjusting recipes to single servings.

“[Nickrand] kept seeing this same thing over and over again, where there’s a very real need for people to learn how to take care of themselves,” says Laura Lerdal, one of the chefs who teaches in the program.“Then there’s also just how triggering food and sense memory is for all these people.”

Every course concludes with a “Celebrating Life With Food” session. Students bring recipes created or enjoyed by dead loved ones and prepare them in mini kitchens decorated with a candle and a photo of them. After the students serve their dishes—which range from Sloppy Joes to complex stir-fries to bright-blue pancakes—the instructors go around the room to hear the stories behind them.

“It’s mostly simple, hearty, stick-to-your-ribs comfort food,” says Lerdal. “And it’s funny because everybody’s, like, ‘It’s not special or anything.’ But it is, because it was your husband’s favorite thing, so why isn’t it special?”

I ask Lerdal what she thinks of recipe gravestones. Though it’s the first she’s hearing of the concept, she loves the idea of a culinary memorial. It reminds her of a poem she often revisits during the class.

“It’s about how, basically, you are recreating through food the footsteps and the actions of the people before you. You use Grandma’s cast iron skillet, the oil crackles and pops, and it takes you back to that time,” she says. “It calls them down to be with you again.”

Lerdal adds that the act of cooking and eating serves as a springboard to difficult conversations on grief. “It makes me really emotional to talk about it, because it’s really intense. But it’s recognizing it. It’s naming how they feel. It’s giving them an opportunity to feel the way they feel.”

If food can facilitate these difficult conversations among those in mourning, why can’t it do so among the greater community? For a small but growing group, the world of recipe graves has become a gateway to discussing death.

I’m standing in a cold graveyard, staring at a stale slice of bread. It’s January 2021 and I’ve driven to the Cemetery of the Highlands in Highland Mills, New York, to view the grave of Constance Galberd. The stone is charcoal-black and clean enough to show my reflection. Atop the grave, nestled among small stones scrawled with handwritten messages of love (“We miss you”), there’s a thin, brown slice studded with dates, raisins, and walnuts.

I knew immediately that this must be Connie’s Date & Nut Bread. After all, the recipe is right there on the stone.

“It was that generation where they baked and they gave things to other people,” her son, Larry Galberd, tells me over Zoom later. “You shared things that you were good at with other people. And her thing was that bread.” That bread was subtly sweet, and, according to her children, perfect when slathered with cream cheese.

When I tell Larry and his sister, Helen Bopp, about the rectangular slice of bread I found on the grave, they’re perplexed. Since Connie always baked the bread inside empty Campbell’s soup cans, the loaves assumed a trademark cylindrical shape. The Galberd family still typically makes the recipe in round cans. They didn’t leave the bread and while they don’t know who made it, they figure it was someone within the community.

It’s possible the mystery bread was left by a stranger. There is, after all, a small group of cemetery enthusiasts who have taken up the cause of sharing and visiting the world’s recipe graves. TikTok creator Rosie Grant is this community’s de facto leader. Grant and Gastro Obscura have a surprising connection: After reading about a recipe grave I covered a few years ago, Grant says she was inspired to start seeking out recipe graves and making the dishes engraved on them herself. Her project has resonated with a surprising number of people eager to learn about and discuss the unique memorials: Since she started in 2022, her posts have garnered 200,000 followers and 8 million likes.

Grant’s graveside ritual consists of making the dish, bringing it to the cemetery, and eating it alongside the resting place of its creator. “I try to have a moment of calm with the person. I thank them for the recipe and think about them,” she says. Sometimes this moment is blissful, like when she ate Margaret Rees Davis’s blueberry pie beside her grave in Seattle, Washington. Other times, it might be a more imperfect kind of tranquility, like when she sampled Marian Montfort’s “Heavenly Daze” apricot ice cream in the pouring rain in Weld, Maine.

Sometimes, Grant has been surprised by others who have come to pay their respects. When she visited the memorial for Kay Andrews, a gray-and-black stone that proudly bears the recipe for Kay’s Fudge in Logan, Utah, she was silently cursing herself for messing up the recipe as another family walked up. They, too, had made the chocolate treat. “Their fudge was so much better. Mine was inedible,” she laughs. After sharing their sweet and chatting over the grave, Grant learned that the couple were locals who often bring their children to the cemetery, fudge in tow, to tell them the stories behind the stones.

Eggener, the art and architecture historian, notes that recipe graves offer something tangible to visitors, akin to memorials with benches or overhead coverings that provide shelter from the sun or rain. “This allows you to take something away from the graveyard, too, besides just the memory or some kind of communion with the dead,” he says.

Perhaps this is why visitors are able to find meaning at a stranger’s recipe gravestone. We love to see graves paying tribute to comfort food because they comfort us. They tell us that even seemingly-quotidian contributions have lasting value. They become shrines to our collective culinary memories of birthdays and bake sales, holidays and Sunday dinners. At these graves, we give our quiet contemplation and leave with our own rekindled memories of food and family—or, at the very least, a really good cookie recipe. What better gift to leave your descendants and your community than instructions for nourishing the body and soul?

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook