This Mechanical 19th-Century ‘Clock of America’ Animates U.S. History

It features a procession of tiny presidents and a light-up Statue of Liberty.

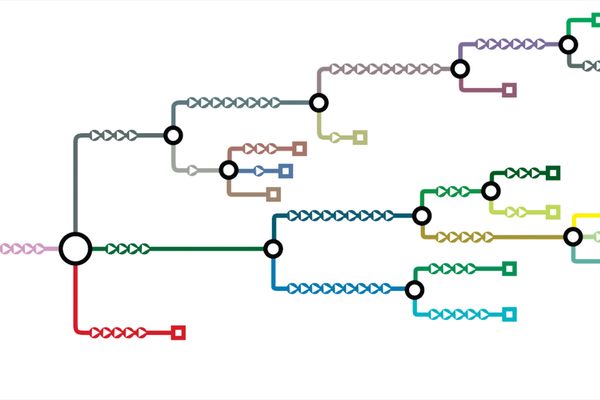

The Great Historical Clock of America, the Smithsonian’s most ambitious timepiece, measures 13 feet tall and comes alive every few minutes.

In the 1890s, a team of now obscure Boston artisans covered its wooden case with scrolling scenery and rotating figures. When it was shipped off for display as far away as Australia and New Zealand, newspapers called it “without doubt, the greatest scientific, mechanical and artistic achievement of the nineteenth century.”

When its mechanism is properly wound, folk tunes tinkle as George Washington pops out of a domed tower and admires a procession of American presidents and Revolutionary War minutemen. A painted fabric view of Niagara Falls cascades behind a seesawing boat. Tableaus show Native Americans encountering the first white settlers. In between models of the Statue of Liberty and a Gettysburg memorial column, galloping horses carry Paul Revere through the Boston suburbs and the Civil War hero Philip Sheridan across Virginia battlefields. The machinery celebrates the passage of seasons and time, too, with zodiac signs and planets and figures representing the stages of life from infancy through marriage and decrepitude.

The video below shows the clock in action.

During its 1890s showings, minstrel singers, sword swallowers and trained gorillas performed alongside the clockworks. It was marketed as an educational survey of “stirring incidents in the early history of our country.”

The clock, after spending decades dismantled and crated in storage, goes on view June 28 in an exhibition at the National Museum of American History, “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith.” Videos will show its newly repaired components in action, but it will not be allowed to perform for the public. Beth Richwine, the clock project’s lead conservator, said that given the fragility of much of its components, “It would be a maintenance nightmare to even try to run it.”

When the clock was first exhibited, newspapers attributed its construction to a Bostonian craftsman named C. S. Chase and his son Albert. The makers sewed tiny realistic clothes for its wood and papier maché figures, and in the clockworks, they combined mass-produced gears with bits of recycled hand drills. An impresario named R. G. Bachelder took it on its first worldwide tours. Little else about its manufacturers and travels is known.

By the 1950s it belonged to a New Hampshire clock collector, a retired lingerie salesman, who cut away part of his barn loft to make room for its dome. When the Smithsonian acquired it in 1979, the mechanisms were only partly functional. To activate its dioramas and folk tunes, Ms. Richwine said, “You could reach in and crank a set of gears.”

For the June display, conservators replaced chains between shafts and cleaned away dirt, corrosion and mold. “The clothing was all very carefully vacuumed,” Ms. Richwine says. A few flaws remain, however. The presidents are not in chronological order, and a handful are missing—were the figures broken or lost on the road, or did the Chases dislike those particular politicians?

The Statue of Liberty also no longer carries a lightbulb in her torch. “We’re afraid to put anything electrical in the middle of all that paper and fabric,” Carlene Stephens, the museum’s curator of clocks, explains.

She has tracked down a few similarly grandiose contemporaries of the Smithsonian’s Great Historical Clock. A turreted timepiece is covered in figures of apostles at the Hershey Story museum in Hershey, Pennsylvania. “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” at the National Watch & Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania, plays hymns and patriotic songs to accompany the motions of figures from the Bible and the American Revolution. On the carved mahogany “Wonderful Clock” at the Detroit Historical Society, “Miniature figures in the base represent different nations which march to music around the globe every five minutes.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook