The Grim History Hidden Under a Baltimore Parking Lot

After an African-American cemetery was bulldozed, families wondered what happened to the graves.

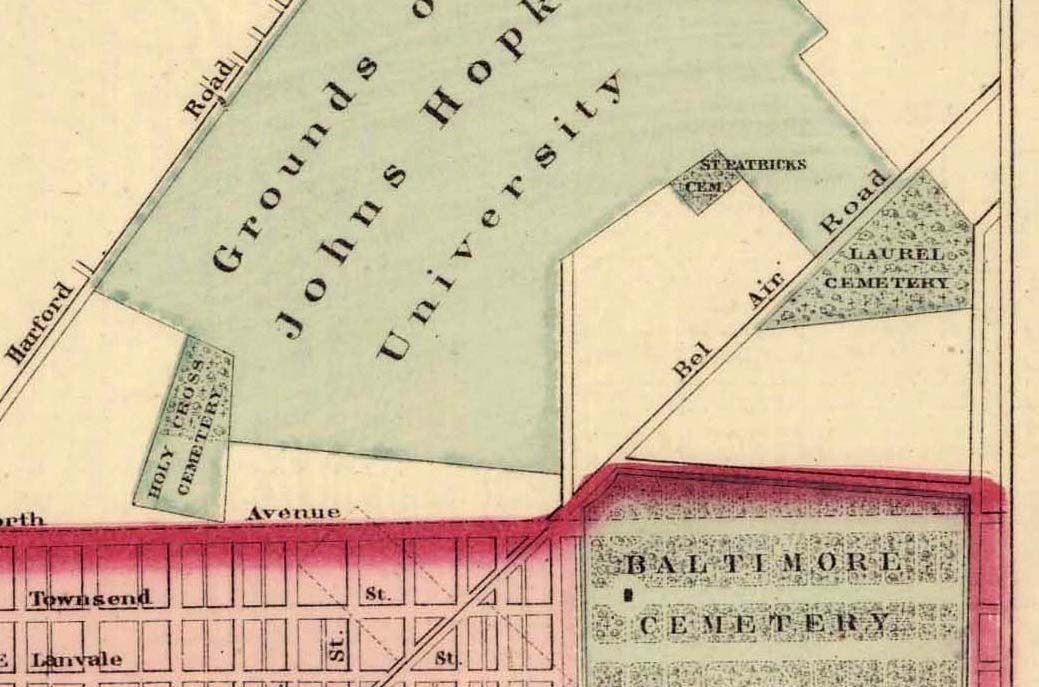

When Laurel Cemetery opened on the outskirts of Baltimore in 1852, its owners advertised a beautiful, peaceful spot, with “high and undulating” grounds, a public chapel, and tree-lined walks. The site had already been used for years for the burial of black servants of wealthier white people. But as the city’s first nonsectarian graveyard for black residents, Laurel Cemetery was supposed to become a place where the luminaries of Baltimore’s black community could be remembered forever.

“All who procure burials here are sure of an undisturbed resting place for all time to come,” an 1858 ad promised.

The life span of that promise fell far short of eternity. Today, the hill is gone. The chapel is gone. The gravestones and walks are gone. On the site of “the city’s most fashionable burying ground,” as the Baltimore Afro American described it in 1951, stands a Food Depot, a discount department store, and a Dollar General, among other commercial buildings.

In the 1960s, over the objections of families with relatives buried there, the cemetery was paved over by developers with political connections. “One day, they put a big plastic fence around the whole thing and started using earthmoving equipment and moving bodies,” says Julius Zuke. A school librarian, Zuke grew up a few blocks from the cemetery, and a couple of years ago he had his students research the site, which has been long forgotten by most of the city.

The developers claimed that they relocated the cemetery, but as Zuke says, “there was always a suspicion in the neighborhood—did they get all the bodies?

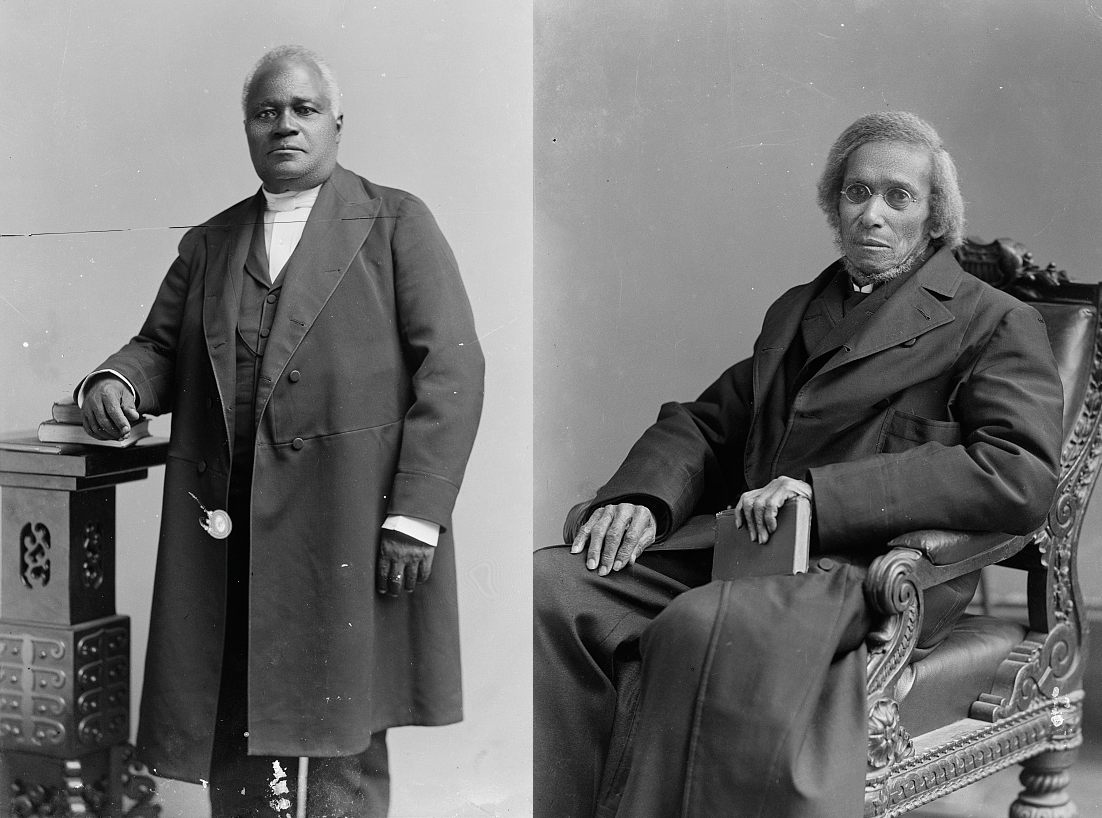

For more than half a century, Laurel Cemetery was a fixture in Baltimore. Behind the wall stood the stately headstones of the Reverend Daniel A. Payne, the first African-American president of an American college, and Alexander Wayman, a prominent bishop of the A.M.E. Church. Cabell Calloway, whose descendants include the famous bandleader Cab Calloway, was buried there, along with many of the city’s upper class of lawyers, politicians, and clergymen.

The obituaries of people buried in Laurel Cemetery, which appeared in the Afro American, contain a world of local history. The people buried there included Samuel Owings, “the first colored job printer in the city,” Isaac Jones, “a well known public cook,” and J. Murray Ralph, “one of the few intimates of the late Frederick Douglass.” There was Mary L. Creditt, “one of the first members of the old First African Baptist Church,” “Ol” Hebron, “one of the best known men about town,” and Samuel E. Young, who “had probably fed more people than any other caterer in Baltimore.” One of the saddest stories was of Myrtle A. Press, an 11-year-old girl killed by a car on her way to church. Many of the people buried at Laurel were born farther south, before the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. One section was set aside for Civil War veterans—240 in all.

But by the 1920s the grace and beauty of the graveyard had started to decline. Complaints began to appear in local papers. City ash trucks were using the cemetery as a dumping ground, and in 1923 the Afro American reported that the cemetery “was in a deplorable state.” Neighbors had even found cattle knocking over gravestones inside the gates. As the city grew, white families moved into new homes built along the cemetery edge, and they started turning their refuse pails over their backyard fences. In 1929, a photographer for the Afro American snapped a picture of an old refrigerator, an outdoor toilet, and other trash littered among the tombstones.

Although the Laurel Cemetery Company had assured its customers and their families that the resting places would not be disturbed in perpetuity, its owners were not prepared to provide that care. (Few cemeteries created in the 19th century were.) By 1924 the company owed enough in back taxes that the city tried sell off a section of the cemetery, ignoring the inconvenient fact that 200 people were buried there. In 1930, the owners tried to raise capital by turning one corner into a gasoline station. In both cases, protests from the community stopped the sales, and soon a group of lot owners formed an association to protect the cemetery.

“This condition does not exist at Greenmount, Loudon Park, Druid Ridge, Cathedral, or other cemeteries in which our white brothers are laid to rest,” wrote Fearless M. Williams in a letter to the Afro’s editor, “and therefore it should not be inflicted upon us.”

By the end of the 1930s, the cemetery was overgrown and almost wild. Local residents started pushing to have it removed altogether. A neighborhood improvement group imagined a playground there. In 1949, the city approved a proposal to turn the site into a public housing project, but the community killed that idea out of concern that it would lower property values. In the end, the Baltimore Planning Commission decided that it would be impossible to transform the cemetery for some other public use.

Instead, the owners of the Laurel Cemetery Company filed for bankruptcy and quietly began the process of selling the land.

Cemeteries, at base, have a simple function. They cordon off the dead and mark a separate space for human remains. For some, a cemetery is a sacred place; for others, bones have little meaning, and once a person is buried, relatives may never return to their graveside. But for a community, a cemetery can have another purpose. As they commemorate the dead, gravestones preserve a story about a place.

“You can put together the biographical details of individuals and spin an ethnographic story about their lives, their struggles, their achievements,” says Lynn Rainville, an anthropological archaeologist who studies historic African-American graveyards. Sometimes cemeteries are the only remaining evidence of those lives. When graves disappear, the story does, too.

As cities grow, cemeteries that were once on the outskirts come to occupy increasingly valuable land. In New York, for instance, burials below 86th Street were outlawed in 1851, but it’s still possible to find historic cemeteries in the densest parts of the city. Trinity Churchyard, where Alexander Hamilton is buried, is in the Financial District. New York Marble Cemetery is hidden in the Lower East Side. But places where less powerful people were buried often disappear beneath new development. Washington Square Park is built atop a potter’s field. The city’s 18th-century African Burial Ground was built over in the 19th century and only rediscovered in the 1990s during a redevelopment project. (Today it is a National Monument.)

Cities still grapple with the problem of old cemeteries. Austin recently created a Cemetery Master Plan after a local group, Save Austin’s Cemeteries, started pushing for preservation. In Houston, an outcry from families held up the bulldozing of a cemetery sold to developers. Chicago built an airport runway over a 161-year-old graveyard. These days, though, when cities and developers do decide to build over cemeteries, there are often state laws in place that dictate the procedures for exhuming and reburying remains.

Back in the 1950s, though, there were few protections for the dead of Laurel Cemetery. The graveyard was in bad shape, but the land itself had immense value—to those who knew how to unlock it.

The group of lawyers and city officials involved in the sale of Laurel Cemetery seemed to know what they were doing. On paper the cemetery wasn’t worth much, so two city officials formed a real-estate company that offered $100 for it in 1957.

Over the next few months, long-standing obstacles were cleared away, with the help of men who ultimately benefited from the sale. A bill that allowed the land to be condemned passed the state legislature. The city settled a dispute with the federal government over part of the land. The Planning Commission approved rezoning that allowed commercial development.

Before long, the realty company had full control of the cemetery. In short order, the land was sold to a developer, by a pass-through company whose owners and stockholders included many of the men who had made the sale possible. By then, the land was valued at $229,660.

Soon after the relatives of Laurel Cemetery’s occupants learned of the sale, bulldozers were knocking over gravestones. The graves, families were told, had been moved to a cemetery in Carroll County, miles away from the city and inaccessible to most of the families whose relatives were buried at Laurel. Families filed lawsuits to stop the development, and the local NAACP chapter took on the case. The city started an investigation into the officials involved in the sale.

Ultimately, though, there was nothing in the law to protect the cemetery or the families of the people buried there. The development went forward, and soon the beautiful, tree-filled cemetery was replaced by a parking lot surrounded by discount stores.

At first, remembers Zuke, the school librarian, some people in the neighborhood hesitated to shop at the new development. Should anyone be buying groceries in what used to be a graveyard? But soon the memory of Laurel Cemetery faded, and few residents of Baltimore recall that it had ever existed.

But in the 1980s, a local genealogist, Alma Moore, dedicated herself to piecing together the cemetery’s history and documenting the names of the people buried there. (The details above come from her extensive research, published in its fullest form in a 1984 issue of Flower of the Forest Black Genealogical Journal, with co-author Ralph Clayton, a researcher who worked at a local library.) In the course of her research, Moore became convinced that thousands of people remain buried under the shopping center’s parking lot.

Although the graves were supposed to have been moved, one of the lot owners who sued the developers told Moore that the new cemetery does not hold all the bodies buried in the original. That made sense to her. The new cemetery was much smaller, with the headstones clustered together. Plus newspaper accounts from the time of the redevelopment reported the removal of, at most, 500 graves. Moore was documenting the names of thousands of people who’d been buried at Laurel. It seemed reasonable to assume that most of those graves had not been moved. But no one knew for sure.

Then, a few years ago, Ronald Castanzo, an archaeologist and assistant dean at the University of Baltimore, came across an old map that included Laurel Cemetery. It wasn’t that far from the university, so he went over to take a look. He saw the parking lot covering the site, but also a small area where grass had been planted. He asked the company that owned the site for permission to excavate, and in 2015 he and a group of students began a small dig.

The soil in this part of the world is acidic and, over time, eats away at buried bones. But Castanzo and his students found human bones, along with the hardware from caskets—hinges and decorative metal details. They also used ground-penetrating radar to scan the parking lot. “It looks like there are a lot of graves still intact,” Castanzo says. Most of Laurel Cemetery was never moved, but bulldozed and paved over.

Stories like this are not rare, particularly in the South, where small African-American graveyards, left behind by families migrating north, have routinely been razed. “One of the only unique things here is the shenanigans about the purchase,” says Rainville, the anthropological archaeologist. The scale of the graveyard is too. It was rare to have a cemetery of this size set aside for a black community in the 19th century. The scale also makes the loss of the place that much more significant. Laurel Cemetery had a record, chiseled in stone, of a huge swath of Baltimore history. In the course of just a few decades it was—willfully, deliberately—erased.

Today the people who rediscovered the story of the cemetery are working to make sure it’s not forgotten again. Both Castanzo and Zuke have been considering ways to have a memorial or a historic marker placed on the site. “It’s an important historic site, and it’s actually a huge burial ground,” says Castanzo. “We’ll probably never be able to reconstruct everyone that’s buried there.” But at least a marker would signal to people what the place once meant, before it became the sort of place that seems to mean nothing at all.

This story originally appeared on January 30, 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook