The Liquor-Soaked Devil Shrines of Bolivia’s Deadliest Mine

In the heart of the Andes, Catholic miners also pray to satanic statues.

If a miner strikes a rich vein of silver in Cerro Rico, a mountain looming over the Bolivian city of Potosí, it is thanks to El Tio. If a miner is crushed to death by a loose rock in the mountain, it is also the work of El Tio. All the miners can do to sate the ambivalent spirit that guards the mountain in the heart of the Andes is leave offerings. The mines are home to more than 600 shrines in his likeness, which the men ritually soak in liquor, bestow with lit cigarettes, and shower in coca leaves. El Tio also accepts the blood of llamas. The church-going miners are happy to oblige.

The miners of this mountain hold the Christian God in one hand and El Tio in the other. The contradictory syncretism is one that reflects the region’s dark, colonial history and how, within Cerro Rico, little has changed since it was first mined 500 years ago.

It’s no exaggeration to say that El Tio’s dark domain shaped the modern world. The mountain was once home to the greatest silver deposit on earth, and its extraction by imperial Spain on the backs of slaves bankrolled their conquest of the New World and fueled the European Renaissance. By 1600, Bolivian silver had increased the supply of exchangeable currency throughout Europe eightfold; Macalester College Anthropology professor Jack Weatherford calls Potosí “the first city of capitalism.”

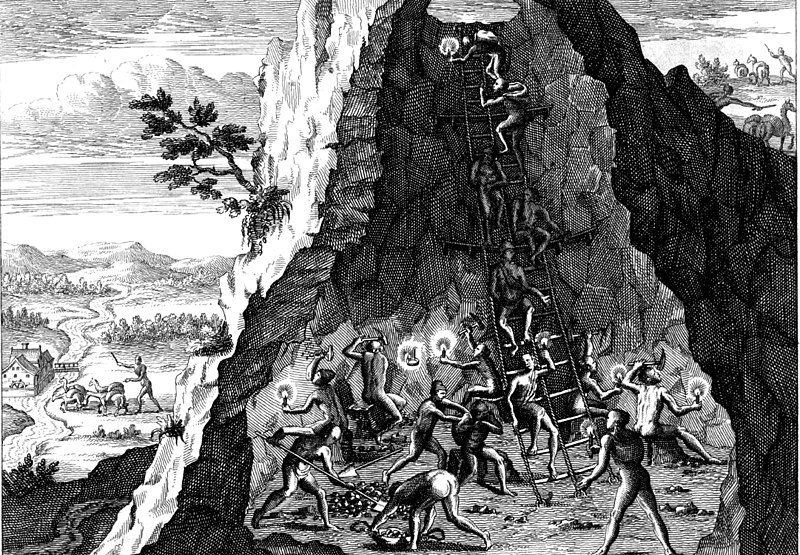

Somewhere between four and eight million Quechuan Indians and enslaved Africans died mining the mountain, earning “The Rich Hill” a darker, if not more accurate nickname: “The Mountain That Eats Men.”

The arrival of Spanish Catholics carried with them the seed that likely became El Tio. Jose Ticona, a third-generation miner and local historian of Cerro Rico, says that conjecture passed down from miners of old offer the only clues to El Tio’s origin. The Spaniards likely refused to enter the mines themselves, he explains, instilling order by introducing slaves to the concept of a maleficent Devil. Told that a lack of obedience and respect for the Devil was the root of all misfortune in the mountain, the miners venerated the spirit in a very Andean manner, creating the niche, underground cult of offering and sacrifice that exists today.

Origin aside, the Spanish certainly created the hellish conditions in which the cult of El Tio thrives. And while the work is now voluntary, the job is no less grim. When the state-owned enterprise regulating the mountain decentralized in 1985, over 30 Quechua-run cooperatives began forgoing safety standards to outcompete one another. They employ child laborers to squeeze through tight shafts and mine without coordinating digging paths. More than 600 unregulated mineshafts traversed by 15,000 workers haphazardly pocket the now-sagging mountain, where unpredictable cave-ins claim the lives of dozens of brave men annually. A 2011 collapse at Cerro Rico’s cap disfigured the once triangularly peaked mountain that is literally the centerpiece of Bolivia’s national flag. The tragic irony is that the mountain is now owned and regulated by Quechuans themselves, and still the mountain kills.

“There is a culture of death,” miner Ibeth Garabito told Al Jazeera. To the miners, everything that happens underground is the will of El Tio. “If you don’t make him offerings, he will punish you,” Basilio Vargas explains to his 10-year-old brother in the 2015 documentary The Devil’s Miner. “He eats the miner. He kills him and then eats his soul.”

While crosses adorn the hundreds of entrances to the mines, the largest open spaces within Cerro Rico are occupied by clay models of the mercurial spirit. “A mine cannot exist without its Tio,” says mine boss Saturnino Ortega in The Devil’s Miner. The horned creature with bulging eyes and a sharp goatee sits upright in his throne, naked, with an unmistakable erection. His mouth and nose are often blackened from a lit cigarette that hangs from his lips. It’s a good omen, miners say, if El Tio smokes it all the way to the filter. The relationship is reciprocal. “We don’t just take the silver,” third-generation miner Antonio Potochij tells me. “We pay the mountain with rituals.”

Relieving the mountain of its resources and living to reap the benefits, the miners repay El Tio in instruments of vice. On Tuesdays and Fridays, the miners offer him coca leaves, hand-roll him cigarettes, and douse him in puro, a 96 percent ethanol they dilute with water and drink throughout the day. Cans of beer often litter the ground at his feet, flags draping his horns and shoulders. “Outside, we believe in God, who is our savior,” says Ortega. However, in the narrow, dusty mines of Cerro Rico, “We ask the Devil for favors, sometimes on our knees. Our belief is split into two worlds.”

While Catholic symbols are forbidden in the mines and likenesses of El Tio are shunned by the Church outside, the cult of El Tio does often spill over into broader Potosino festivities. On the first of August, miners and their families gather to pitch blood from a sacrificial llama about the entrance of the mine and their faces before barbecuing the sacred animal. “We bathe the entrance with llama’s blood so he doesn’t drink our blood,” explains one man in The Devil’s Miner. In the tradition of Wilancha, miners push a flaming cart filled with liquor, candy, and a live llama speeding into the mines as sacrifice.

The deification of this spirit is a mark of the region’s identity. The people of Potosí absorbed and transformed Christian mythology in propagating El Tio, writes anthropologist Michael Taussig, “to give poetic expression to the needs of the oppressed.” The retention of these traditions over centuries is a testament not only to the strength of Andean religious culture, but the continued trials of Cerro Rico’s miners. The offerings of liquor, llamas, and tobacco are symbolic; the sacrifice of the mens’ own bodies are not. As long as the fearless miners of Potosí are so exploited, El Tio will be fed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook