Respect the Hammock, One of Humanity’s Greatest Creations

In praise of an excellent idea with a long, complicated history.

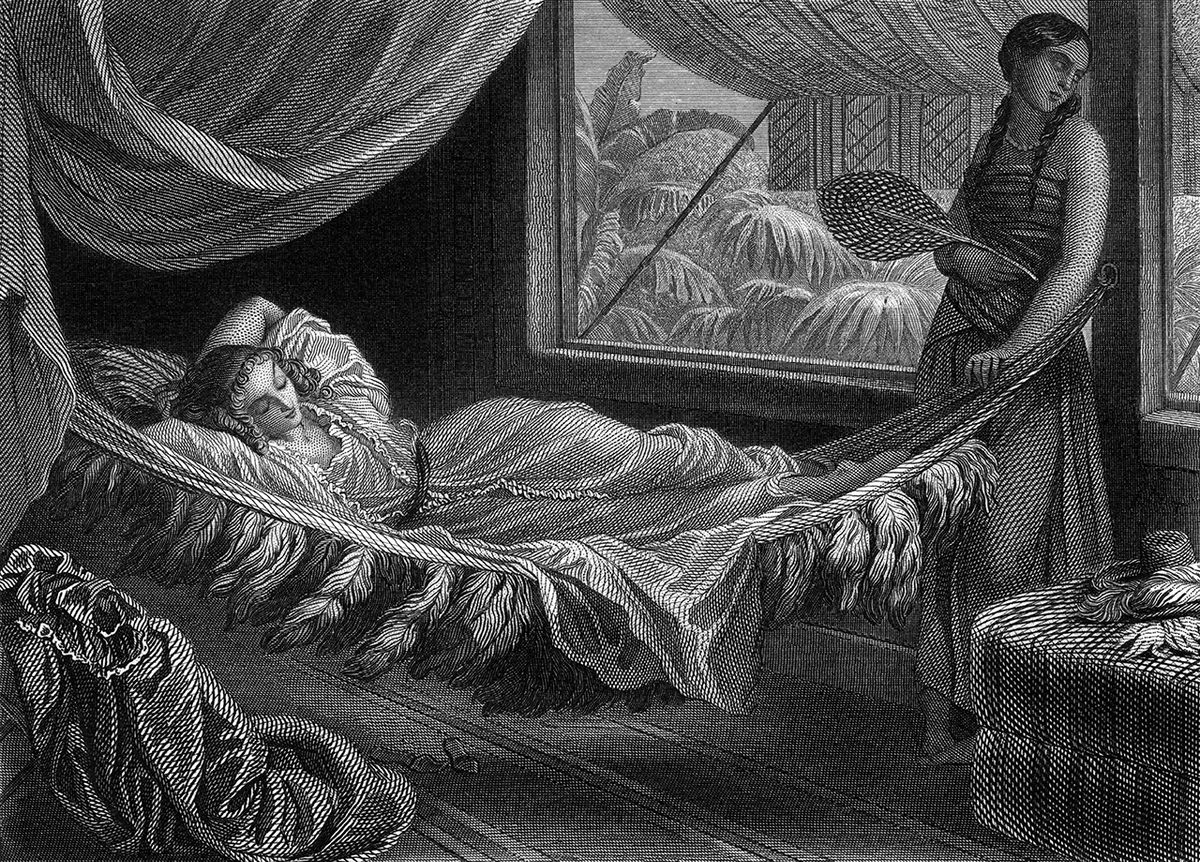

The hammock has become an intrinsic part of vacation iconography, a shorthand for the act of relaxation. It is a symbol, often a performative one, of leisure, of escapism, of a kind of luxury—in environment, if not materials.

This, of course, all comes from the minds of people who live far away from where the hammock was invented. The hammock is, at its core, just an incredibly good idea, one that has spread almost immediately wherever it is introduced. If you see a hammock, you want to tell people about it, and get one for yourself. Yet, like many things with a more or less global reach, it has taken on different meanings over time, not all of them positive.

The early days of the hammock are not well understood, but they certainly did come a long time ago. Woven of organic materials that eventually decompose in tropical environments—where pretty much everything decomposes eventually—hammocks were well established in the Caribbean when the first Europeans landed there. The English word “hammock” derives from the Spanish hamaca, a direct loanword from the Taíno languages of the Caribbean.

Just about all of the major early European expeditions to the New World talked about the hammock. Columbus described it in his journal: “Their beds and bags for holding things were like nets of cotton.” Bartolomé de las Casas, the first real European historian to go to the Americas, went on at length about them. In his book Historia de las Indias, written between 1527 and 1559, de las Casas described beds “like cotton nets,” with elaborate, well-crafted patterns. The ends, he wrote, were made of a different, hemp-like material, to attach to walls or poles.

The materials used for hammocks at the time of European contact likely varied. Cotton is mentioned in the historical record, and it was probably used, at least sometimes. The other material de las Casas described is almost certainly fique, an extremely hardy, rough textile made from the tough leaves of the maguey plant—a close relative of agave.

De las Casas said that he adored the hammock, because it was so hot and humid that this style of bedding was far preferable to the European options: mattresses filled with straw or wool for the very wealthy, straw pallets for the less wealthy, piles of straw or nothing at all for most people.

By the time Europeans made it to the mainland, hammocks were also fully established in the cultures of Mexico, Central America, and the hotter parts of South America. Their utility is obvious: They elevate the sleeper well above the ground, away from tropical insects and reptiles, and the woven netting maintains airflow—vital in the heat. They’re also incredibly portable. In the Caribbean, de las Casas described hammocks as being fairly stationary, attached to poles within a permanent house, but the form is versatile enough to serve those who live in one place as well as those who sleep somewhere different every night.

The hammock was likely the first human-created product (as opposed to a crop or mineral) that the European conquerors decided they simply must have. In the Spanish and Taíno War of San Juan–Borikén, or the Taíno Rebellion of 1511, the Spanish often took hammocks as spoils of war. Within 50 years of Columbus’s first journey to the Caribbean, hammocks had become the standard bedding on the ships of both the Spanish and English navies. They’re great at sea, swaying gently much of the time, and fully collapsible to take up as little precious space as possible.

It took a further couple of centuries for the hammock to gain any import other than “great idea from the people we’re destroying.” Its next associations weren’t much better. Soraya Serra-Collazo, of the University of Puerto Rico, documented the strange journey of the hammock in a 2014 paper in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. “During the 18th century,” she wrote, “hammock use has been reported by Spanish officials and the clergy as means to claim the laziness of local people.”

Alexander O’Reilly, an Irishman sent to Puerto Rico by King Charles III of Spain, was one of many prominent Europeans to brand the Taíno as lazy. He complained, upon his 1765 trip to Puerto Rico, that the land was simply too abundant, the climate too nice. “With only five days of work,” he wrote, “a family had enough plantains for the whole year.” The hammock was specifically singled out as a symbol of the laziness of the people of Puerto Rico: Nothing this comfortable and un-European could possibly be acceptable.

The denigration of something as basic as a sleeping method reads as an attempt to disparage an entire people, to make them feel inferior and erase their cultural heritage. The association between hammocks and laziness has been incredibly enduring—for good and ill. Essayist Richard Hedderman, in 2013, wrote, “Few other contrivance [sic] so invite such joyous abandon to sloth and indifference as the hammock, and it is justly emblematic of pure lassitude.” Paul De Smit, a guy who runs a store in Los Angeles called “Exotic Hammocks” says he tells people he’s in “the relaxation business.”

Europeans, and those of European descent who live in cool climates, have never stopped exoticizing the theoretically easy-living, leisurely, romantic existence of the tropics. And the hammock is wholly of the tropics—a direct, practical response to a hot, humid environment. Alongside topless indigenous women (at least, up until the last few decades), palm trees, white sand beaches, and cocktails with tropical fruit, hammocks are now emblems of a chill lifestyle. They’ve become essential for social media influencers—a component of an ideal life, so much so that they pop up in the feeds of algorithm-constructed fake influencers created by marketing teams.

To share a photo of yourself in a hammock is to brag, in a way that a photo of yourself in bed is not.

There is no consensus on the spiritual home of the hammock today. (China, on the other side of the world from the hammock’s birthplace, is a major manufacturer.) But undoubtedly one of the great hammock cultures of the world is to be found in El Salvador, a country slightly smaller than the state of Massachusetts, a country that Americans, if they think of it at all, associate with gang violence and fleeing refugees.

“For me, [the hammock] is also a metaphor for Central American migrants in that, like the snail or turtle that carries its home on its back, Central Americans bring our homes with us in our hearts and make a home where we choose to relocate,” says Karina Oliva Alvarado, a Salvadoran lecturer in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The capital of El Salvador, San Salvador, is nicknamed El Valle de Las Hamacas—the Valley of the Hammocks—due to the city’s location. Nestled among active volcanoes, in a zone where earthquakes hit on a regular basis, the city is accustomed to rocking from side to side. But El Salvador is also literally a country of hammocks. Concepción Quezaltepeque, in the north, hosts a hammock festival every year. Hammocks are everywhere, a Salvadoran staple, throughout the socioeconomic spectrum. “Hammocks swing from doorways, inside living rooms, on porches, in outdoor courtyards, and from trees. Just about everywhere a hammock can be hung, there will be a Salvadoran swinging from one,” according to travel writer Wade Shepard.

Hammock retailers around the world swear by the skill and beauty of the Salvadoran hammock. Companies, such as this Brooklyn-based “design collective,” go to great lengths to procure Salvadoran hammocks over all others.

Salvadoran hammocks are traditionally woven, says Oliva Alvarado, with a vertical weave technique, in which the hammock-in-progress is strung between two vertical poles. Sometimes called a “Maya hammock,” this particular type is rather heavy, due to the quantity of string used in them. The string is thin, and strands cross over each other, rather than knotting at intersections. They’re also gathered at each end, unlike the more American styles that feature a spreader bar to make hammocks more rectangular and bed-like.

El Salvador exports a lot of textiles, T-shirts especially, but serious hammock-heads—there are forums for them—prize the Salvadoran ones.

Hammock history is complicated. In El Salvador and other countries where the hammock is essential and very old, it has taken centuries to reclaim them as a fundamental symbol and thing of value. For some of those from colder climates, the stereotype of the hammock as a symbol of laziness—staining the people who make and use them when not on vacation—has never really left. The converse, in which the hammock is a symbol of luxury and leisure, is problematic, too. The hammock itself? Just a great idea.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook