A North Carolina Artist’s Search for a Lost Sound Uncovered a Dark History

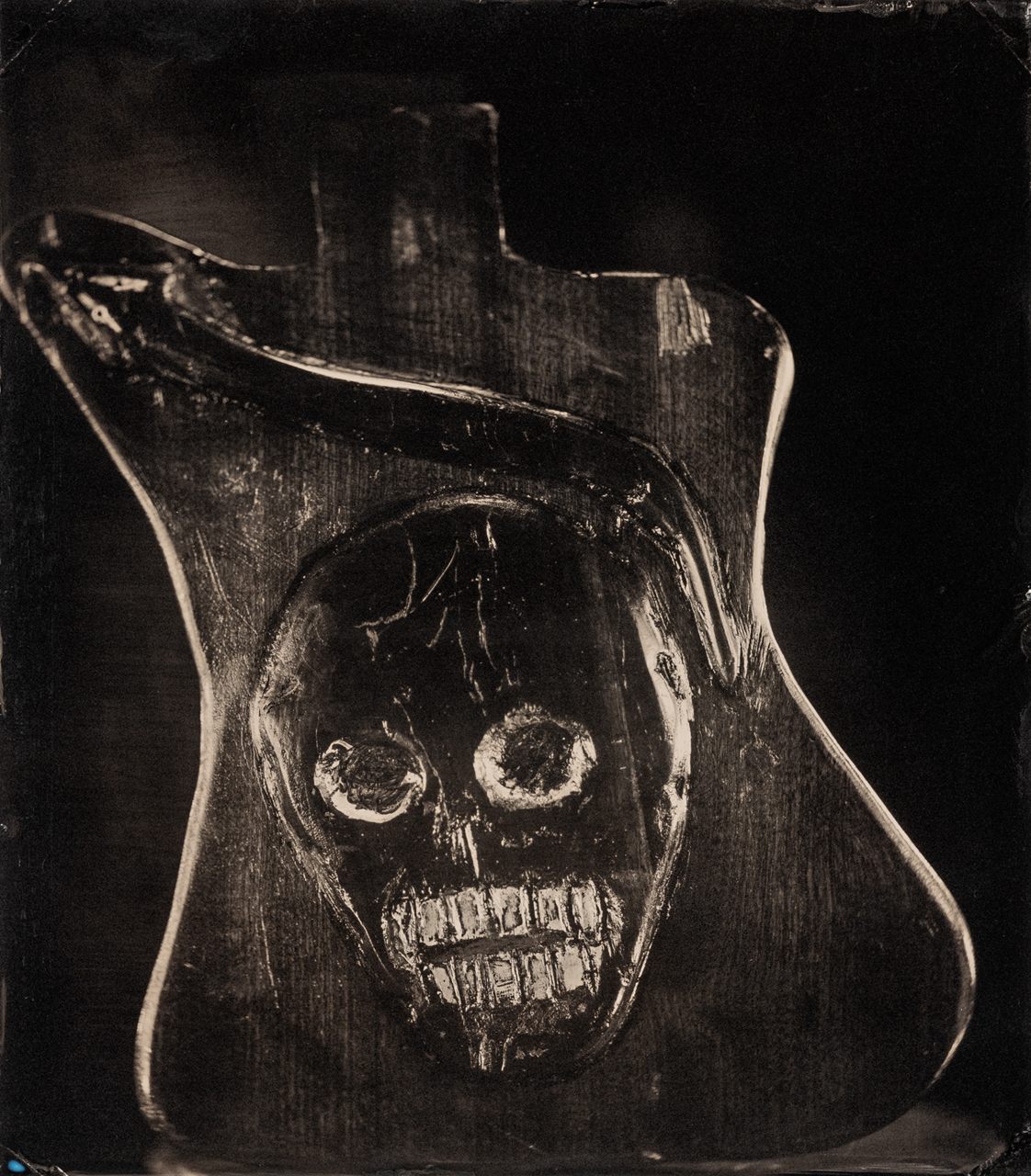

Freeman Vines honors a lost Black life with his ‘Hanging Tree Guitars.’

Artist Freeman Vines was captivated for a long time with an unforgettable sound he once heard from a gospel musician’s guitar. At his home near a tobacco field in the small rural town of Fountain, North Carolina, Vines then spent over 50 years hand-carving guitars out of found wood, in a relentless search for that special tone. Despite decades of creating guitars, he never found that sound again. But he found other revelations.

In the new book Hanging Tree Guitars, a collaboration between Vines, photographer Timothy Duffy, folklorist Zoe Van Buren, and published by The Bitter Southerner in association with Music Maker Relief Foundation, Vines spoke of the salvaged materials that inspired him to create these guitars, some of which appear more like sculptures than functional musical instruments. “Wood talks to me … Wood has a character, like the good cooks found out that food has a character,” Vines said in the book. More importantly, the wood that called to him had history, or a sense of spirit or purpose: the front step of a tobacco barn, a wooden trough, a piano soundboard. Of particular significance to him were two planks of black walnut wood, given to Vines by a man who had claimed that they were from a tree where a Black man had been lynched.

Vines did not work this wood to pursue a special sound so much as he delicately carved his way through history, in a part of North Carolina once known to be the heart of Ku Klux Klan territory. Though he could not confirm for sure that the wood was what it was claimed to be, Vines had a more important story on his mind: “What bothered me was: Where was he hung at? Who was he?”

Born in the area in the 1940s, Vines experienced a hard upbringing during the Jim Crow era, and still had to navigate race and class—carefully and sometimes fearfully—in more recent years. With the help of collaborator Duffy, whose artistic wet collodion photographs grace the book’s pages, and appear as if they are from another era, they discovered in 2018 the location of a tree that one woman claimed was the site of the last lynching in Fountain. There, in 1930, it was reported, 200 masked people participated in or watched the brutal murder of one man. Upon learning the identity of that man—29-year-old Oliver Moore’s death was reported widely in the press—Vines made guitars from the old black walnut planks, and haunted them with skull and snake motifs. “I reckon, in my imagination, it’s the man that died on that tree,” said Vines in the book. When asked if he believes there are spirits in the hanging tree wood, he continued, “You know they are. They’ve got to be. They’ve got nowhere else to go. The wood, actually everything, is involved spiritually. A little spirit rubs off on everything.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection from the book of Duffy’s photographs documenting Vines’s guitars and the landscapes that also inform his work.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook