Meet the Appalachian Apple Hunter Who Rescued 1,000 ‘Lost’ Varieties

Tom Brown’s retirement hobby is a godsend for chefs, conservationists, and cider.

As Tom Brown leads a pair of young, aspiring homesteaders through his home apple orchard in Clemmons, North Carolina, he gestures at clusters of maturing trees. A retired chemical engineer, the 79 year old lists varieties and pauses to tell occasional stories. Unfamiliar names such as Black Winesap, Candy Stripe, Royal Lemon, Rabun Bald, Yellow Bellflower, and Night Dropper pair with tales that seem plucked from pomological lore.

Take the Junaluska apple. Legend has it the variety was standardized by Cherokee Indians in the Smoky Mountains more than two centuries ago and named after its greatest patron, an early-19th-century chief. Old-time orchardists say the apple was once a Southern favorite, but disappeared around 1900. Brown started hunting for it in 2001 after discovering references in an Antebellum-era orchard catalog from Franklin, North Carolina.

Detective work helped him locate the rural orchard, which closed in 1859. Next, he enlisted a local hobby-orchardist and mailman as a guide. The two spent days knocking door-to-door asking about old apple trees. Eventually, an elderly woman led them to the remains of a mountain orchard that’d long since been swallowed by forest. Brown returned during fruiting season and used historic records to identify a single, gnarled Junaluska tree. He clipped scionwood for his new conservation orchard and set about reintroducing the apple to the world.

Brown has dozens of apple-hunting tales like these from the nearly 25 years he’s spent searching for Appalachia’s lost heirloom apples. To date, he has reclaimed about 1,200 varieties, and his two-acre orchard, Heritage Apples, contains 700 of the rarest. Most haven’t been sold commercially for a century or more; some were cloned from the last known trees of their kind.

“These apples belong to the [foodways] of my grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ generations,” says Brown, who was raised in western North Carolina.

Thousands of varieties probably still exist, but saving them is a race against time. The people who hold clues about their locations are typically in their 80s or 90s. Each year trees are lost to storms, development, beetles, and blights. Brown has devoted his later years to beating the clock.

Ironically, Brown didn’t know what a heritage apple was until he stumbled on them at a historic farmer’s market in 1998.

“There was a little stand with a bunch of strange-looking apples laid out in baskets,” says Brown.

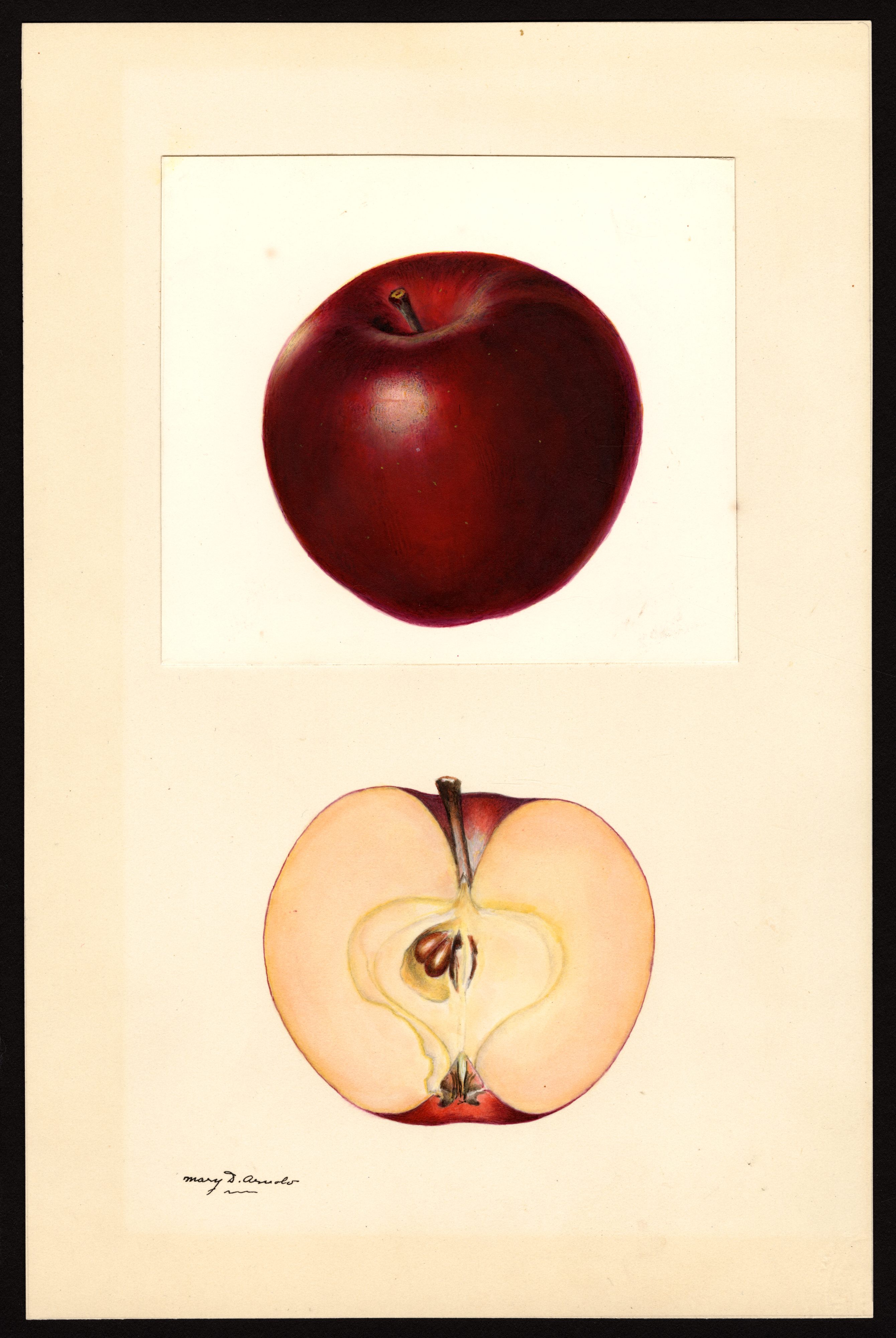

Colors ranged from bright green to yellow-streaked, sunset pink, and purplish black. Some were plum-sized, others as big as softballs. They had names like Bitter Buckingham, White Winter Jon, Arkansas Black, and Billy Sparks Sweetening. Tasting trays brought a smorgasbord of flavors and textures.

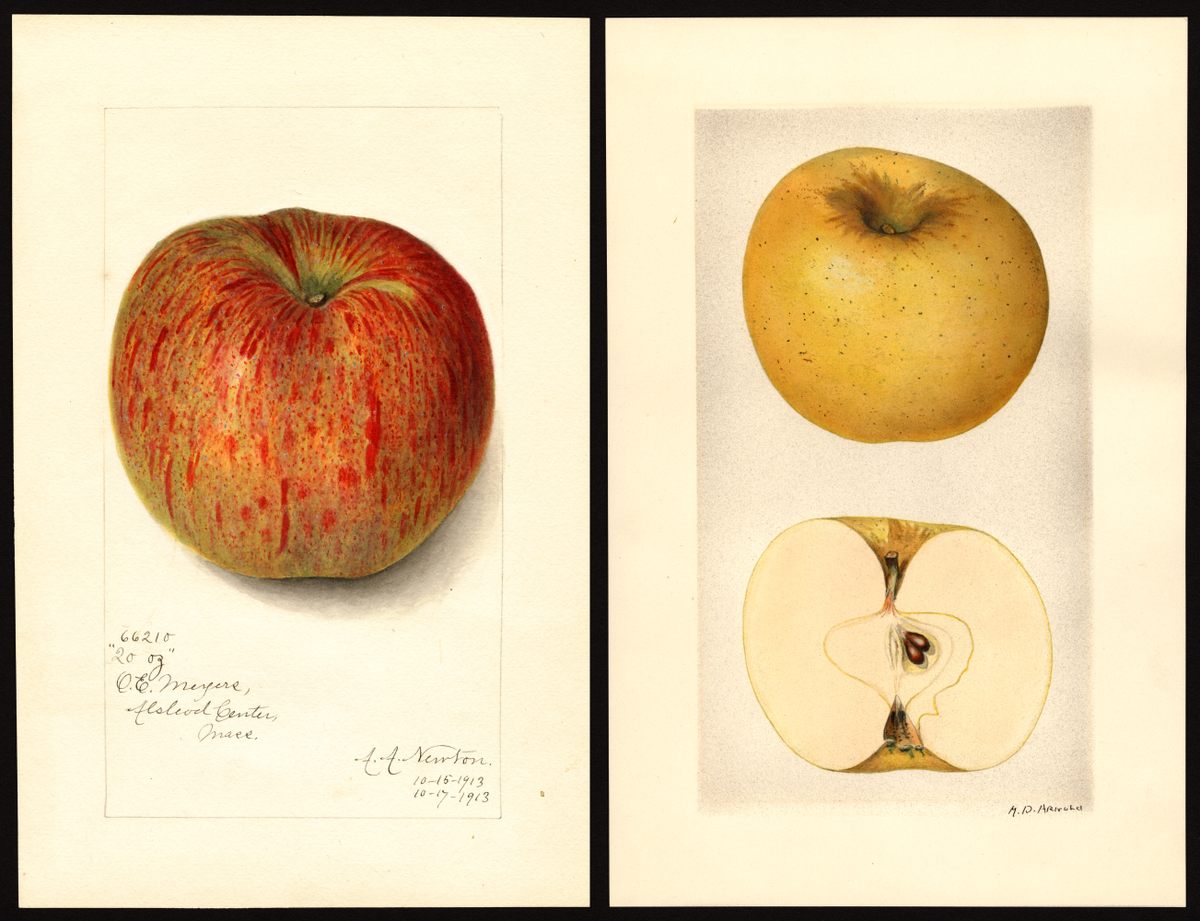

Brown tasted Jonathans that had rosé wine-colored flesh. Rusty Coats were soft like pears and sweet like honey. The mammoth Twenty Ounce was crisp with a tart, peachy finish. Semi-firm Etter’s Gold brought peony bouquets and grape flavors. Grimes Golden were sweet with a hint of nutmeg and white pepper.

Brown’s enthusiasm led to a conversation with the vendor, late orchardist Maurice Marshall. The varieties of apples he was selling were standardized in the 1700s and 1800s, and had vanished from commercial circulation by 1950. Marshall had obtained most of the scionwood for them from elderly mountain homesteaders. But two or three varieties came from clippings taken during apple-hunting expeditions at the ruins of old orchards. What’s more, hundreds of lost apples could likely be reclaimed at similar sites throughout Appalachia.

“That part stayed with me,” says Brown. “I kept thinking: ‘How neat would it be to find an apple nobody’s tasted in 50 or 100 years?’”

Then it struck him: Had so many interesting, great-tasting fruits really just disappeared? It seemed impossible. Brown threw himself into researching the history of Appalachia’s heritage apples. What he learned was awe-inspiring and devastating.

Commercial orchards in the U.S. grew about 14,000 unique apple varieties in 1905, and most of them could be found in Appalachia, says William Kerrigan, author of Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard and a professor of American history at Muskingum University.

The diversity was rooted in early colonial precautions.

“Water wasn’t always safe to drink, and episodes of sickness from contaminated water gave that substance a questionable reputation,” says Kerrigan. Fermented beverages were the go-to alternative. Importing wine was expensive, and native pests killed Old World grapes. Apple orchards were easier to maintain and more utilitarian than growing fields of barley for beer, so cider became the colonists’ choice beverage. By the mid-1700s, virtually every East Coast farm and homestead had an apple orchard.

The settlement of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountain region spurred an innovation boom.

High-but-not-too-high elevations, hot, humid summers, and rich, deep soil nurtured by consistently rainy winters produced ideal growing conditions, writes Kerrigan in Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard.

By the early 1800s, the Shenandoah Valley had become the top U.S. growing region. Commercial orchards were proliferating throughout eastern Appalachia. Experimentation was relentless.

Growers did things like cross tannin-rich indigenous crabapples with Old World cider staples, writes Kerrigan. The efforts produced new varieties such as the Taliaferro, which Thomas Jefferson championed as the world’s greatest cider apple.

But apple varieties were cultivated for more than cider.

For Appalachian farmers and homesteaders, “a diverse orchard was fundamental to survival and good-eating alike,” says Brown. Residents were expert gardeners and developed varieties that matured at different intervals, tasted unique, and catered to specific culinary functions.

“The goal was to be able to pick fresh apples from June to November, and have a diverse supply of fruit throughout the year,” says Brown. Thick-skinned, late-ripening varieties provided wintertime pomaceous treats. Others were tweaked for applications such as frying, baking, dehydrating, making vinegar, and finishing livestock.

Apples were the garden’s crown jewels, says Appalachian Food Summit co-founder and renowned chef, Travis Milton. People took pride in having something unique to brag about to their neighbors.

But Appalachian traditions around heritage apples were eroded and ultimately destroyed by urban migration, factory farming, and corporatized food systems. Conglomerates negotiated national contracts and switched to apples that matured fast and were suited to long-distance shipping. By 1950, most smaller orchards had been forced out of business—Milton’s grandfather, for instance, sold the family’s Wise County, Virginia, orchard to a coal company to save his cattle farm. Gardens began to disappear.

By the late 1990s, U.S. commercial orchards grew fewer than 100 apple varieties—and just 11 of them accounted for 90 percent of grocery-store sales. Experts estimated 11,000 heirloom varieties had gone extinct.

“It upset me to learn about that,” says Brown. Two-hundred-fifty years of culinary culture had been squandered. “These were foods that people had once cared about deeply, that’d been central to their lives. It felt wrong to just let them die.”

But if Marshall was right, some of Appalachia’s heritage apples could still be recovered. And Brown was looking for a retirement hobby. His experience as a scientist would bring calculated organization to searches. The project would let him explore and learn more about the history of rural Appalachian communities.

Brown realized he’d stumbled onto “what could only be described as a ‘calling.’”

Becoming the world’s most accomplished heirloom apple-hunter brought a steep learning curve.

Marshall introduced Brown to a network of aging, small-scale heritage orchardists (none kept more than 20 varieties) who taught him the basics of identifying, cloning, grafting, and maintaining trees. He discussed lost apple varieties and made lists of names including characteristics, former growing locations, and rumors of where trees still existed.

Connecting with regional historical societies yielded old orchard maps, fruit-grower association newsletters, and names of former owners and workers. Pomological historians helped Brown track down vintage orchard catalogs with drawings and descriptions for thousands of lost varieties.

His early search-and-rescue attempts centered around former hotbeds of production, such as North Carolina’s Brushy Mountains. The two-county region was home to more than 100 commercial orchards in 1900. Brown advertised in area newspapers seeking information about old apple trees.

“The response was exciting, but also kind of [a reality-check],” says Brown. He fielded dozens of calls, but few brought concrete information. Most callers were in their 80s and 90s, says Brown, and told childhood stories where “old man such-and-such had a tree with 20 different types of apples grafted onto it.”

“Up to then I hadn’t grasped how much detective work [this] was going to require,” says Brown.

Years of ad-hoc efforts helped him develop central strategies for hunts. First he gathers clues about trees’ possible whereabouts. For instance, discovering the address of someone’s great-grandparents who once kept a large orchard can pinpoint a rural community where special trees may still exist. Brown then draws a radius around the property and canvasses nearby homes. He stops at local businesses to make inquiries.

“When I explain what I’m doing, most people are really receptive,” says Brown.

For instance, a conversation with an 80 year old at a country store in northeast Georgia led Brown to amateur orchardist Johnny Crawford. Crawford put Brown in touch with elders in the Speed family, who ultimately helped him locate a treasure-trove of heirlooms in a rural area, including the Royal Lemon, Neverfail, Candy Stripe, and Black Winesap.

When Brown finds a tree, he takes clippings and returns during fruiting season to identify them. He compares leaves and apples to catalog entries, and uses photos to correspond with experts for further verification.

Brown drives about 30,000-plus miles a year and devotes around three days a week to apple-hunting. His partnerships with municipalities and non-profits such as the Southern Foodways Alliance help establish reclaimed varieties at additional orchards and ensure their survival.

“Saving an apple from the brink of extinction is a miraculous feeling,” says Brown. “It’s incredibly rewarding—and incredibly addictive!”

Today Brown’s orchard is filled with clones of trees recovered in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. He divides time between apple-hunting, tending trees, donating scionwood to nonprofit heritage orchards, and selling about 1,000 saplings annually.

Brown’s work has been commended by conservationists and culinary professionals alike. Chefs like Travis Milton are stoked to have hundreds of new flavors to experiment with. Craft cidermakers say reintroduced heirlooms are inspiring a cider renaissance.

“Tom has helped redefine what’s possible,” says Foggy Ridge Cider owner, Diane Flynt, who won a James Beard Foundation award in 2018. She says heirlooms such as Hewes Virginia Crab and Arkansas Black are for Appalachia what noble grape varieties like Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon are for Bordeaux.

Brown is thrilled the apples are being put to good use. But he’s quick to note that many still need saving. And they’re getting harder to find.

“It takes me probably 20-30 times more work and a lot more driving to locate one new tree,” says Brown.

But that doesn’t deter him. Brown has come to think of restoring Appalachia’s heritage apples as his “true life’s work.” While he hopes to recover another 100 varieties or more in his lifetime, experiencing just one more find would be reward enough.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook