For Sale: A Hidden Trove of Correspondence With Bob Dylan

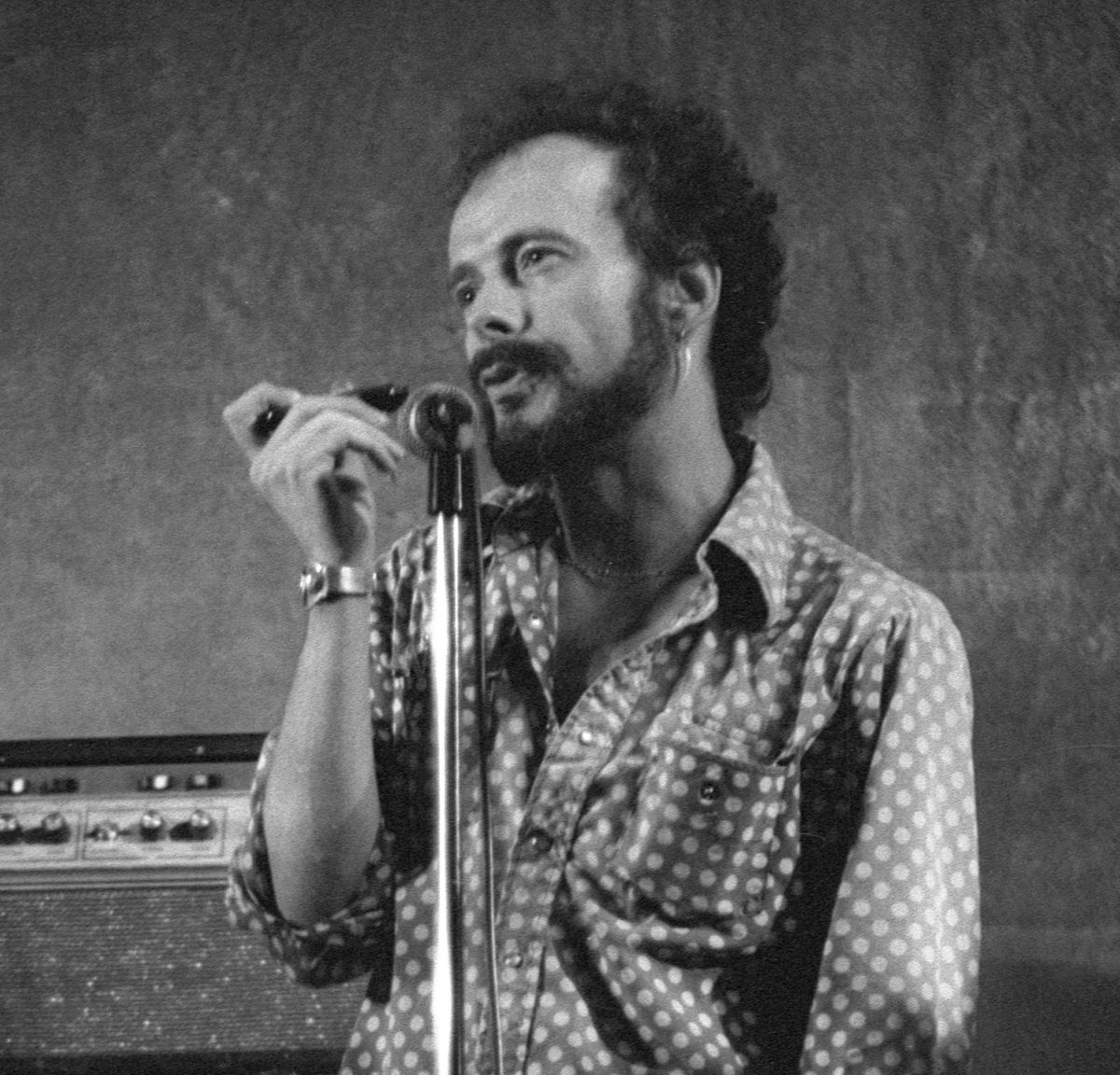

The papers of Tony Glover, “musician’s musician” and journalist, include many other luminaries as well.

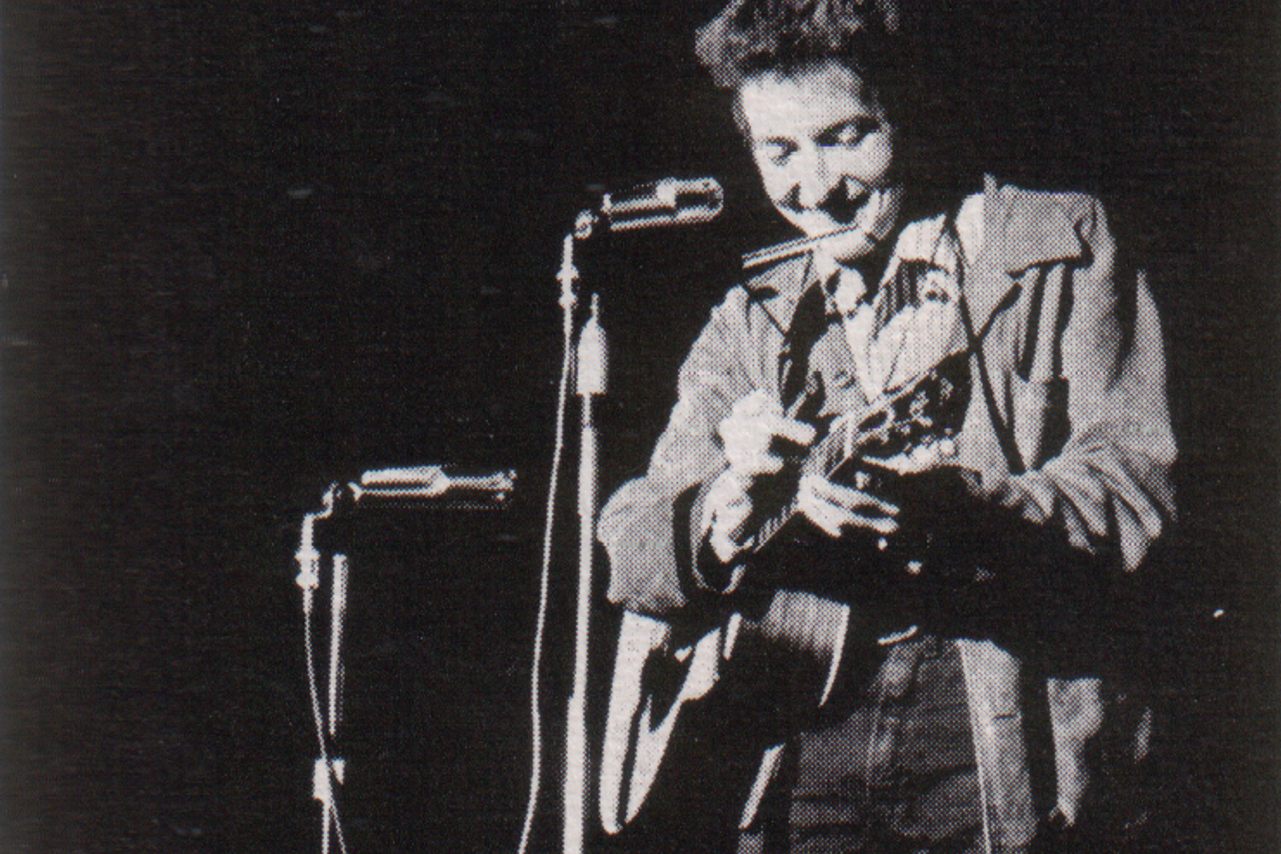

Tony Glover, in the estimation of at least one esteemed critic, was one of the best harmonica players in all Minneapolis, where an impressive folk music scene had emerged by the 1960s. “I couldn’t play like Glover or anything and I didn’t try to. I played mostly like Woody Guthrie and that was about it,” wrote fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan in Chronicles: Volume 1, his 2004 memoir. “Glover’s playing was well known and talked about around town, but nobody commented on mine.”

It wasn’t long, of course, before Dylan skipped town for New York City, and we all know how that went. For many years, however, the famously enigmatic star sustained an unusually close relationship with Glover, who stayed behind in Minneapolis, and was not only an admired blues musician but also an accomplished music journalist. Before he passed away in 2019, Glover cultivated a substantial and highly personalized collection of Dylaniana, principally correspondence between the two that cast the legend in a more intimate (though still highly idiosyncratic) light. Some 169 items from Glover’s archives, extending well beyond Dylan to other giants of classic blues and rock, will hit the block at Boston’s RR Auction in November 2020. At press time, the highest bid (over $10,000) belonged to a book of poetry signed by its author—The Doors’ Jim Morrison—inscribed “to Tony Glover.” Other major signatures in the collection come from Jack Kerouac, Patti Smith, and Joan Baez, to name a few.

Second in the bidding, behind the Morrison book, is a January 1962 letter to Glover handwritten by Dylan upon a recent arrival in New York. “Hey hey hey it’s me writing you a letter,” begins the note from the future Nobel laureate. “Back now in that city and thinking of all that whistling harmonica music you are making back there in that dungeon hole gets me thinking and talking to my good girlfriend about the harp player I knowed—I looked high and wide and uptown and downtown for that book you wanted and I feel so bad, I can’t find it,” Dylan continues, sadly without naming the elusive book. After discussing some gigs and financial woes, Dylan concludes, “My girlfriend says that you don’t sign your full name to friends so—Me, Bob.” This is the kind of thing that simply sat in Glover’s archives for decades, a hidden glimpse behind a carefully crafted veil of celebrity.

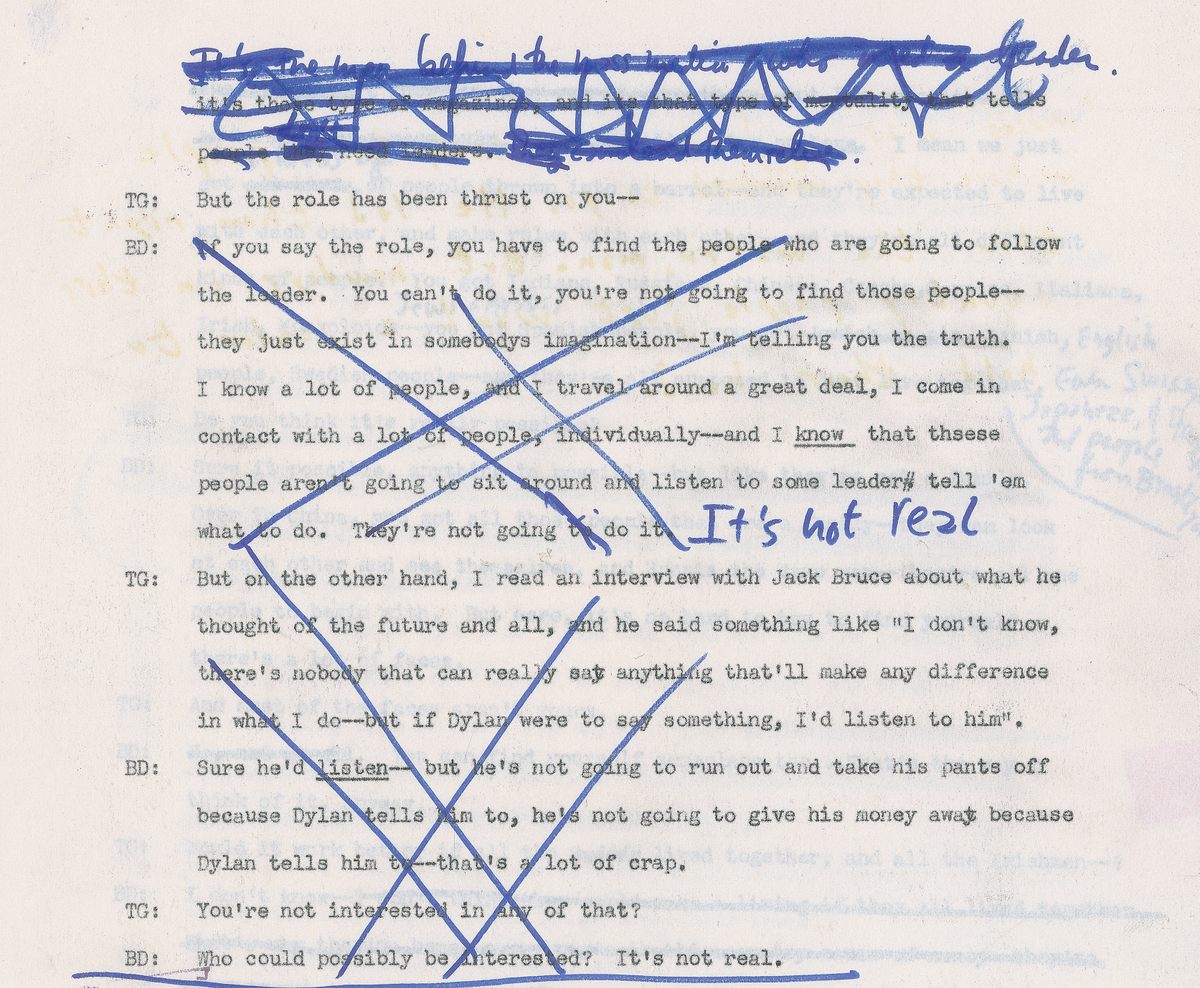

“You just don’t see” handwritten letters from Dylan, says Bobby Livingston, executive vice president of RR Auction. “You just don’t see autobiographical details in Bob Dylan’s own handwriting”—handwritten lyrics aside. Even more rare than these letters is a recording and transcription of a 1971 interview Glover conducted with Dylan, intended for Esquire but ultimately never published. (Ironically, in light of this auction, lengthy snippets were printed 49 years later in Rolling Stone, in a piece by historian Douglas Brinkley.) In the interview, Dylan candidly discusses why he didn’t keep his birth name (Robert Zimmerman); his notorious performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where fans booed him for going electric; and the comparative merits of George Harrison and John Lennon. Most enticingly and decidedly on-brand, Dylan himself picked up a pen and edited the transcript of his own remarks. On one page, which Livingston calls “a piece of art,” Dylan crosses out an entire section and simply writes, “It’s not real.” On another, he corrects his own lengthy self-assessment with a pithy, classically Dylanesque suggestion: “My work is a moving thing.”

As was Glover’s. His wife, Cynthia Nadler, met him in the 1990s, when these rock ‘n’ roll adventures were in “the ancient past.” Glover, still working as a musician, rarely spoke of his famous friends. If it came up naturally in conversation, she says, he might share that he’d played harmonica onstage with the Allman Brothers Band, but he was otherwise busy making his own new music. (She recommends “Elegy #2” and “Uncertain Blues,” both from Ashes in My Whiskey, for unacquainted listeners.) She didn’t know about much of the Dylaniana in her own home until after Glover died. Some of it, inconspicuously stored in boxes, could easily have been thrown away if she hadn’t taken a closer look.

And it’s a good thing Nadler lifted those lids. Glover, Livingston explains, belonged to that first generation of college-aged students, in the 1960s, who began to engage with and revive an older folk blues tradition from the American South. Indeed, included in this collection is a letter from the bluesman Brownie McGhee, describing his collaborator Sonny Terry, whom Glover was researching. It’s work like that that helped bridge McGhee’s generation with Glover and Dylan’s. And it will be vital for what Livingston calls “the next bridge” following in their wake.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook