A New Mobile App Allows Tourists to Explore the Effects of Atomic War in Hiroshima

Some say it tells an incomplete story.

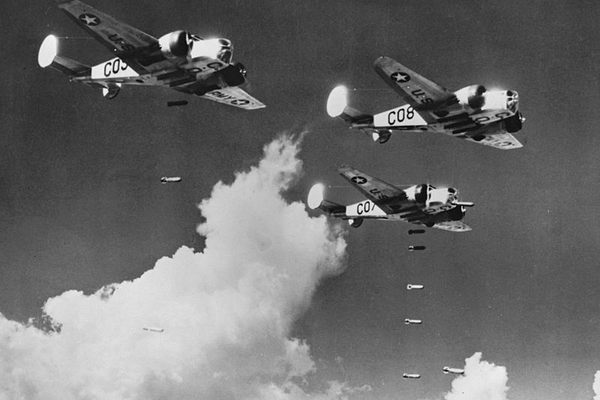

At 8:15 in the morning on August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped by the U.S. military on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, instantly killing tens of thousands of people.* Many people became sick due to radiation, and the final death toll rose to 135,000—although some estimate it much higher.

More than 70 years later, the city has mostly recovered from the blast, but its legacy remains. The Genbaku Dome, now called the “A-bomb dome,” is a skeleton in the middle of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, a constant reminder of the day war laid the city to waste.

The city of Hiroshima wants tourists who visit the city to see for themselves the consequences of atomic war. In October, they released Hiroshima Peace Tourism, an interactive map that allows visitors to see specific sites affected by the bomb. The mobile app has four walking and bus tours of the city, ranging in length from three to eight hours, with routes that stop by memorials, cultural centers, museums, and wrecked buildings. For each site, the app provides the story of the place as well as pre- and post-bomb photos.

The app lists how far each site was from the hypocenter of the bomb. For example, Fukuro-machi Elementary School was 1,500 feet away. After impact, the gutted school became an evacuation shelter and first-aid station. The site is now a Peace Museum, and visitors can see scrawled messages on the walls of the stairways, where survivors kept track of who was alive and who was missing.

Visiting Hiroshima to witness the impact of the war is an example of “dark tourism,” a historical reminder of devastation and suffering, in the same vein as visiting Auschwitz or the 9/11 Memorial. However, Hiroshima hopes to promote itself as a symbol of peace, not war.

“We want visitors to understand and appreciate the city’s commitment to peace,” a city official told The Japan Times. Hiroshima has been a vocal proponent of nuclear disarmament, and has formally protested hundreds of cases of nuclear testing.

But visitors to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and other stops along the interactive tour, might find part of the story missing, says the museologist Chia-Li Chen at Taipei National University of the Arts, who studies the intersection between museums and human rights education. She says the museums in the city are not forthcoming about Japan’s own role in the war.

“I think, at least in the beginning, they were trying to make meaning for themselves, meaning from their suffering, so that’s why they positioned themselves as an anti-nuclear city in search of peace,” she says. But, Chen says, many believe that Japan has not sufficiently acknowledged their own wrong-doings during the war. “I think there is a tendency that they want to educate their people and their children in certain ways that identifies themselves as a victim.” (It should be noted that the Japanese government has criticized the U.S. for not apologizing for dropping the bombs.)

For example, none of the four walking routes include any of the military history of Hiroshima, which contained an army base. Japan has been often criticized for not acknowledging or educating their children about the violence and horrors inflicted by Imperial Army of Japan during the war, such as the Nanjing Massacre in China and the sexual enslavement of hundreds of thousands of “comfort women,” mostly from China and Korea.

In a 2010 study in the peer-reviewed journal Museum Management and Curatorship, Chen examined the comments left by visitors at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. She says some foreigners as well as some Japanese tourists were critical of the lack of context about Japan’s role in the war.

Chen, who visits post-war human rights museums all over the world, says Hiroshima’s Peace Tourism campaign would be stronger if their museums were more rigorous in examining their own history and open about Japan’s role in perpetuating suffering in World War II. Neither the city nor the Peace Memorial replied to a request for comment.

“You can’t just say, ‘I want to pursue peace,’ and then peace will come to you,” Chen adds. “You have to analyze the causes of a war and really think deeply about what happened. It’s not an easy task.”

*Correction: This post previously stated the Hiroshima bombing occurred on August 9, 1945. It occurred on August 6, 1945.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook