The Legendary, Lavish Dinner Parties of South Dakota’s Divorce Colony

For a time, wealthy divorce seekers headed to the frontier.

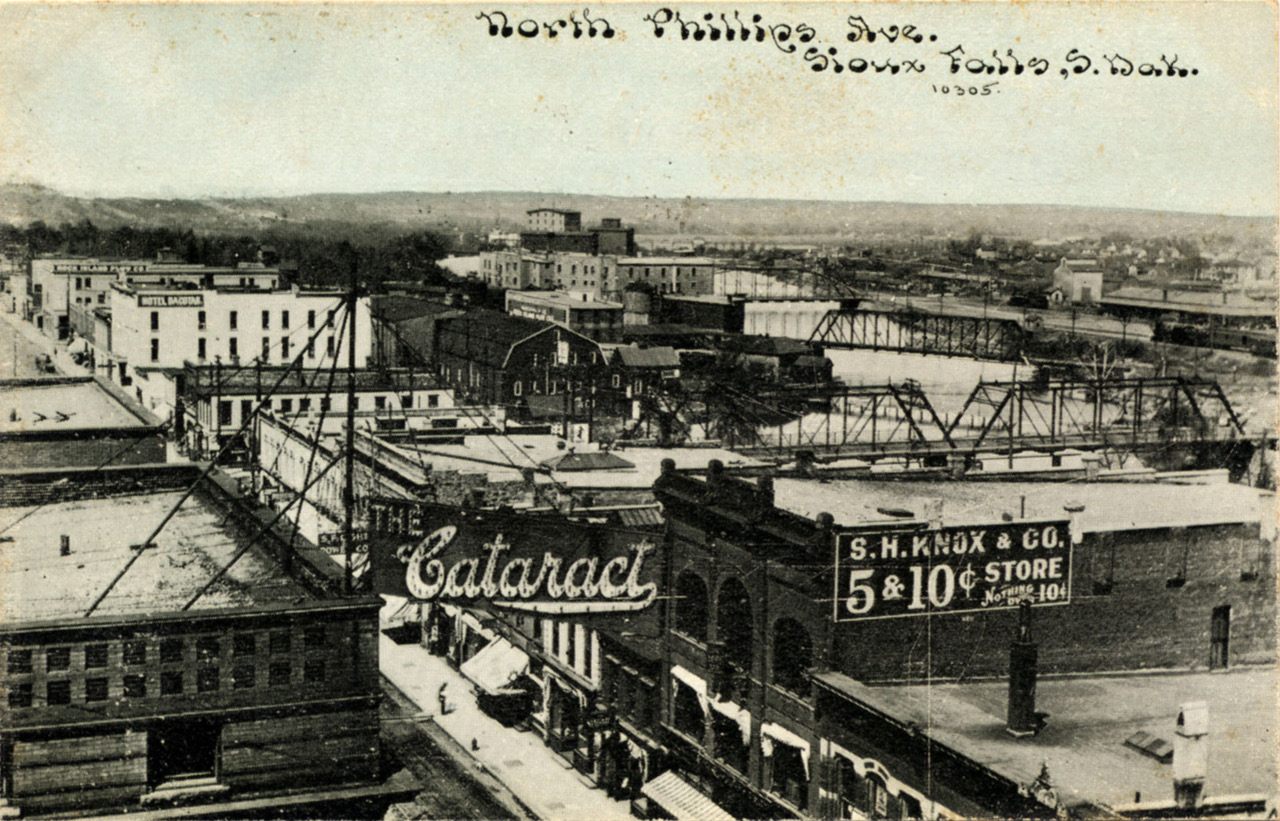

In October 1901, Manhattan playboy Freddie Gebhardt celebrated his divorce decree with a lavish dinner at the Cataract House Hotel in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. He treated guests to a four-course wine supper (each course paired with a complementing wine), and his menu included “delicate viands from the Atlantic Coast,” French wines, oysters, and a large array of imported coffee and fruit, all served by waiters in black tie. “No guest was allowed to retire until he committed the unpardonable offense of rolling from his chair jag shot,” the gossip column, Rum-inations reported.

There was a reason Gebhardt picked The Cataract to hold his celebration. From 1891 to 1908, the frontier town of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, became a haven for women—and some men—escaping bad marriages. They arrived by train, fleeing states whose laws only granted divorces for “proven” adultery or physical abuse. Many fled their families as well as their spouses; the church line was that divorce was immoral, and wives were often counseled to stay with their partners, no matter how abusive.

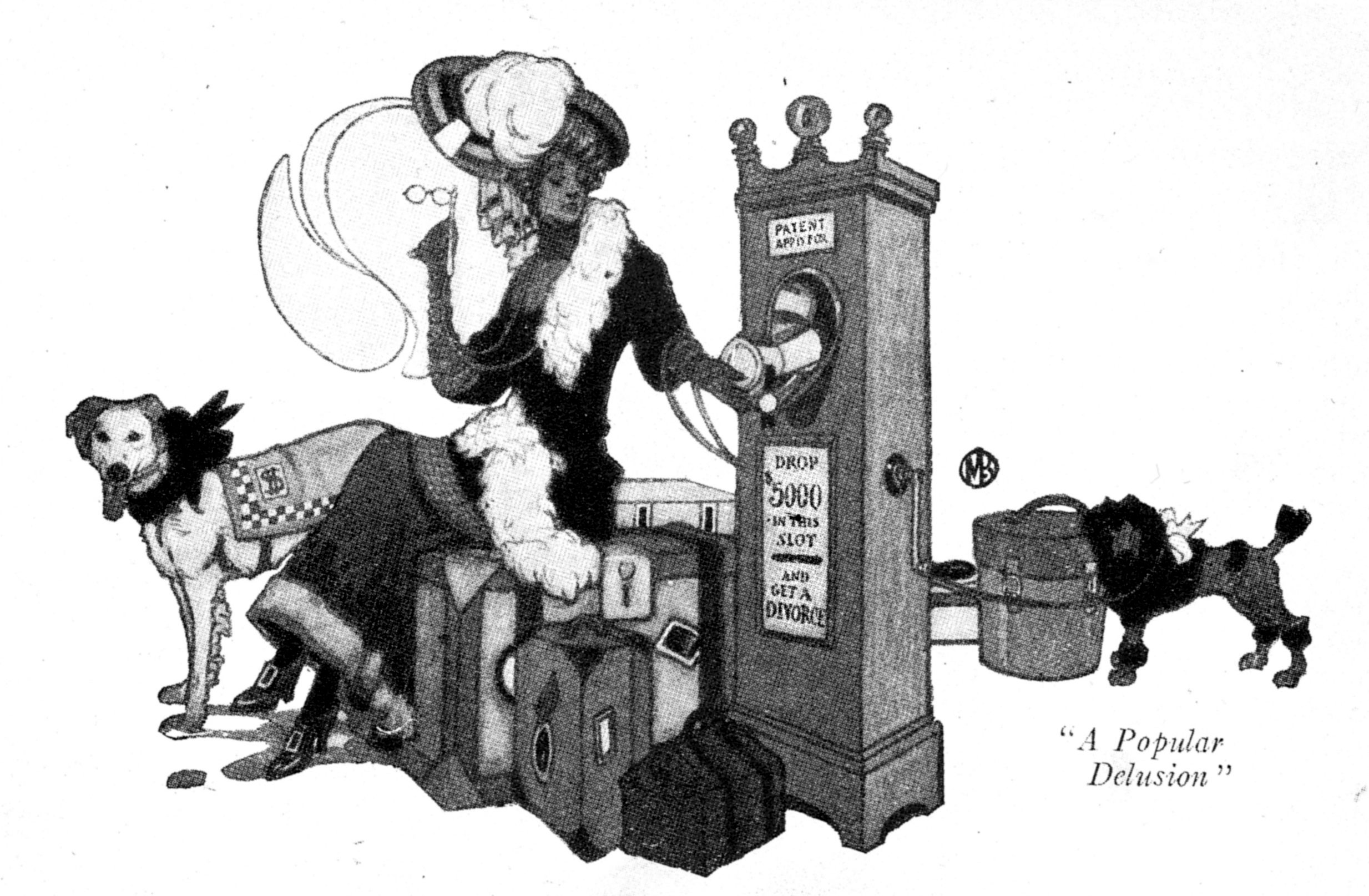

Due to its frontier status, South Dakota had some of the most relaxed grounds for divorce in America, available to all of its residents. Becoming a resident required living in the state for only three to six months, so wealthy divorce seekers made short-term moves to Sioux Falls. Enterprising lawyers and hoteliers capitalized on the lax laws by advertising their services in different states. The options for the unhappily married among the working class, who could not afford a months-long relocation, were essentially limited to separation or desertion. But many who had the means sought out Sioux Falls’ notoriously soft-hearted judge.

This moneyed migration put Sioux Falls on the map. In 1903, Lewis Oren Harris arrived in Sioux Falls after being shot by in the arm and chest by his father-in-law, who was furious his daughter had wed without his say-so. Nonetheless, the family refused to consent to a divorce, saying it would reflect poorly on them. His trigger happy father-in-law threatened to fill him “full of lead” if a decree was granted. Harris’s story was breathlessly reported in newspapers, along with many others at the divorce colony, and the coverage helped turn the town into a divorce mecca, an unexpected side effect of the state’s lax laws.

Critics took notice, and Sioux Falls became a nationwide point of contention for those for and against the relaxation of divorce laws. As April White writes in The Atavist Magazine, South Dakota’s own senator proposed that the federal government regulate divorce laws to end situations like Sioux Falls’ and “preserve the family and the home.” He was not the only anti-divorce crusader, and this jeopardy hung over every divorce proceeding.

While uncontested divorces could be resolved in 15 minutes, many cases dragged on for months, and accordingly, the Cataract House Hotel became known for its divorcees—and the lavish dinners they threw when their divorce was granted. “The law of the colony was that following the granting of the divorce decree the one so favored would give a divorce dinner,” John Emmke, former hotel manager of The Cataract House Hotel, told the Sioux City Journal in 1909. He noted that Gebhardt’s event was the most lavish dinner, costing around $50 a head, or approximately $1,470 per person in today’s money. Bankrolled by a $100,000 a year inheritance, Gebhardt’s excesses were famous in and out of Sioux Falls. “It’s still a subject of reminiscence in Sioux Falls,” Emmke said eight full years later.

The Cataract House Hotel was an anomaly when it was built in 1871, a luxury hotel with 14 beds and two parlors in a still-developing town. The developers predicted demand would grow, and they were right; the confluence of six rail lines and their daily imports proved irresistible to guests heading west who sought the comforts of home. Visitors found the city picturesque and the local Sioux history fascinating. “All these were attractive to the set that has little to do but search for new sensations,” reported The Oakland Tribune in 1906. To cater to more guests, the hotel went through two more builds by 1884, before it burned to the ground in a firework accident in 1900. Quickly rebuilt, its final iteration was five stories tall, with 175 bedrooms (including 50 en-suites) and a high-class restaurant, bar, and grill room. “Absolutely fireproof,” they advertised.

The farewell receptions of successful plaintiffs varied in extravagance, but it was common for celebrants to request The Cataract’s imported “high roller” champagnes. Most divorcees were happy for the hotel to cater their end-of events; on February 1, 1891, the hotel menu included boiled Kennebec trout, smoked tongue in jelly sauce, sirloin beef with dish gravy, turkey, saddle of fall lamb, chicken fricassee, and scalloped oysters. The menu got more exorbitant every year, and by June 2, 1900, dinners included Russian Caviar, salted peanuts, saratoga wafers, roast ribs of prime beef, new potatoes in cream, chicken potted Maryland style, new German waxed beans, and calves brains, larded.

Some divorcees looked for catering further afield. When Pauline Pearsall’s divorce was finalized in 1892, she celebrated with a large order from her favorite steakhouse, Delmonico’s in New York. Servers shipped the food 1,350 miles to the Cataract House Hotel, where she’d resided for the last five months. For extra dazzle, she wore a wedding dress to the event, and distributed $1,000 in party favors. Other hotels might have looked askance at outside food, but The Cataract’s motto was “we strive to please.”

It’s no wonder the Cataract House tried so hard to please—their guests were a cash cow.

“A restaurant and grill room were fitted up the likes of which did not exist west of New York,” commented George Fitch in a 1908 issue of The American Magazine. “The manufacture of divorces … has made wealthy men out of [Sioux Falls] hotel keepers.” To keep their guests entertained, every four months the Cataract House threw a ball “given with all the eclat of Fifth Avenue in New York,” Emmke said.

Other Sioux Falls divorcees held multiple parties; first at The Cataract House, and then when they returned home ring-less. In 1906, Sophia Florence Diesenger, a Cataract House divorcee, threw a themed divorce dinner in New York. “Like Sioux Falls at Home!” proclaimed The Baltimore Sun. The menu was folded like a court document, and each dish was cunningly related to her divorce. There was Lobster a la South Dakota, Frizzled Terrapin, Alimony Sauce, Beef Cold shoulder a la Counsel fees, Shrimp Salad with lawyer’s dressing, and lemon cakes with interlocutory cakes.

Celebratory divorce dinners were not unique to South Dakota. Men and women freed from bad marriages thanks to progressive laws often held banquets—reported celebrations date from 1890, in London, France, and Boston. A three-act comedic French play, Divorçons, which debuted in 1880, focused on the dissolution of a marriage and ended with a “divorce dinner” in a popular restaurant. It became a movie in 1915.

In Sioux Falls, divorce and its associated industries added an estimated $250,000 a year to the local economy. But despite the revenue the divorcees brought in, much of Sioux Falls religious community was unhappy with their hometown profiting from the dissolution of marriage. They petitioned for a change in the state’s laws.

On January 1, 1909, the residency requirement was raised to 12 months, effectively closing down the colony. Future divorce seekers headed to Reno, which had a six-month residency requirement. The Cataract House Hotel stayed open, but its best days were behind it, and it finally shuttered in 1970. However, for those who had the chance to stay at its peak, it was a life-changing experience. “It was a six months’ sentence for the divorce seeker, with no time off for good behavior,” noted former hotel manager John Emmke. “In a measure, it was a gay life.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook