How a 4-Year-Old’s Letter to His Father Survived the Civil War

Scribbles from home, kept safe on the battlefield.

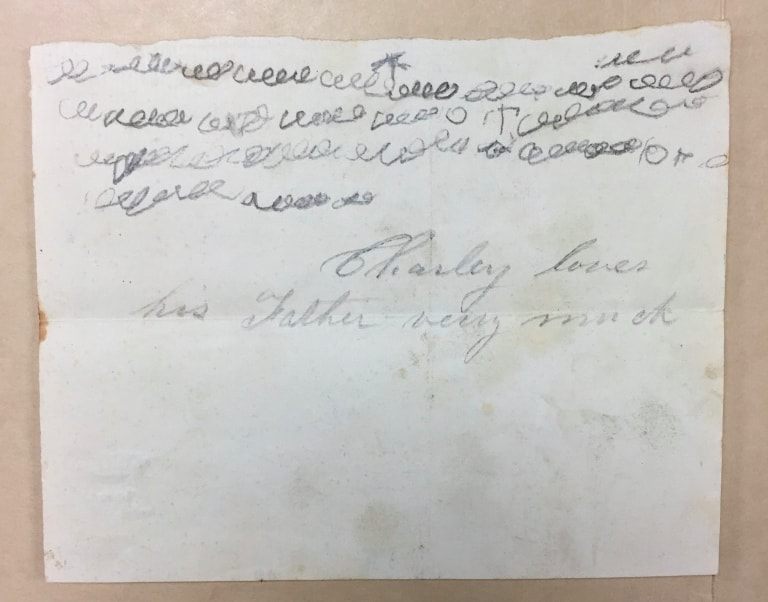

Precious scrawls and squiggles. (Photo: David Plotz)

At first glance, it’s hard to see why New York’s Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History would hold the above letter in its collection. The yellowed paper holds a few lines of loops that look to have been lazily scribbled in pencil—the kind of thing you might doodle out of boredom when a call center operator places you on hold. The catalog entry lists its contents as “Mostly illegible scribbles.”

Beneath these scribbles, though, is a clue: the phrase “Charley loves his Father very much,” written with the same pencil, but in a legible, even elegant, hand.

The Charley in question was Charley Burpee, who was about four years old in 1864—the year he scrawled those loops and scribbles. He was writing to his father, Thomas, a soldier from Connecticut who began serving in the Civil War as a Union Army captain on July 12, 1862. Within a few months of receiving his son’s letter, Thomas was wounded at Cold Harbor, Virginia. He died two days later. Charley’s scribbles were among the personal effects given to the family when his body was shipped home.

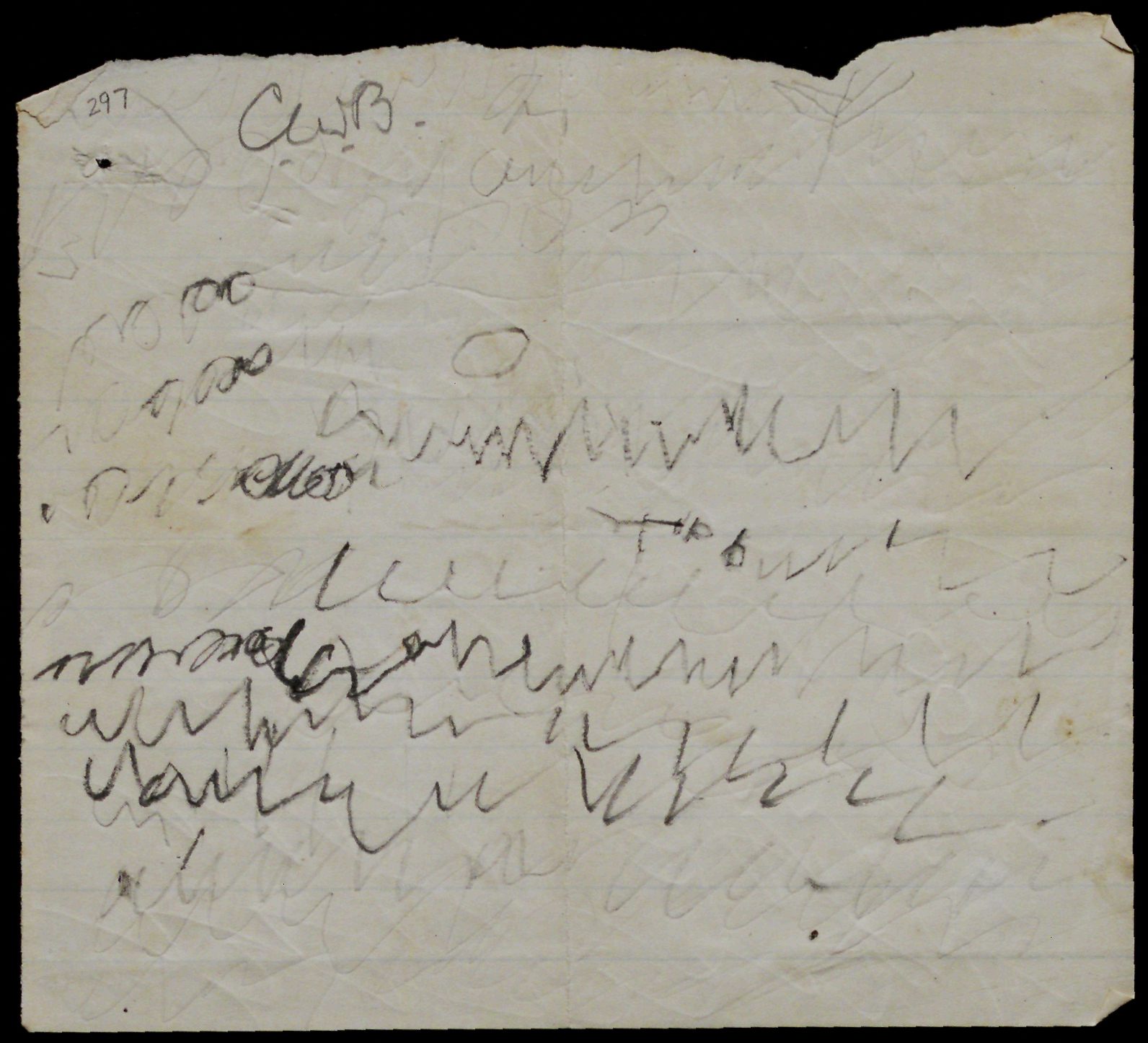

More scribbles from Charley. (Photo: To Thomas Burpee, Charllie Burpee, Courtesy of The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02744.297)

Charley’s letter is a rarity. While many letters written by Civil War soldiers have survived, there are few remaining letters that were written by soldiers’ families and delivered to the battlefield. “In general, letters from home don’t survive,” says Sandy Trenholm, Curator and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Collection. Soldiers had to carry every possession in their haversacks, and non-essential items, even ones with sentimental value, tended to be jettisoned.

For Thomas Burpee to have held onto Charley’s letter, “it must have really meant something to him,” says Trenholm. “I think it survived because he missed his children and he wanted to feel close to them. He was holding onto it.”

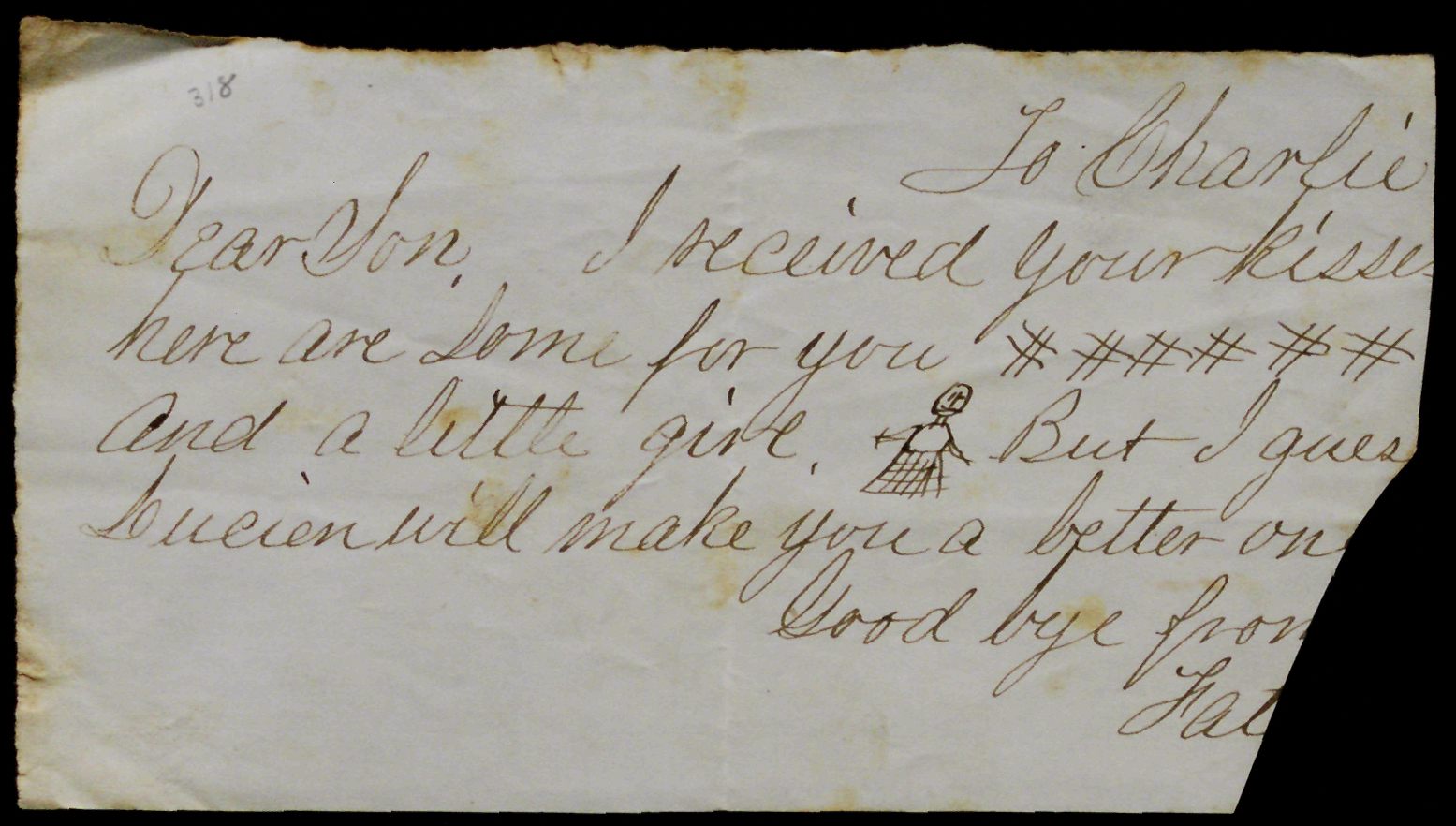

A letter from Thomas Burpee to his youngest son. (Photo: To Charley, Thomas F. Burpee, Courtesy of The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02744.318)

The Gilder Lehrman Institute, which maintains an extensive collection of Civil War documents, has over 500 items relating to Thomas Burpee, his wife, Adeline, and their two children. From these papers, it’s been possible to get a sense of the soldier’s life and his relationship with his family. “You feel like you know them,” says Trenholm, “like they’re a friend of yours.”

Captain Burpee kept another letter from Lucien, his elder son. Written in February 1864 when Lucien was about eight, it’s a stream-of-consciousness insight into life back home in Connecticut: “I go to school every day. Mother says that she will get me a present if I will learn well. We have had two snow storms. Did you get that Valentine I sent you.”

Knowing Lucien penned those words within months of his father’s death is sobering, especially when you discover that Thomas Burpee’s story had a gruesome final twist. “This is a little disturbing,” says Trenholm, “but one of the letters we have, it’s from a chaplain in his regiment, and it sounds like they forgot to embalm him before they sent the body home. The chaplain was trying to explain that it wasn’t his fault—that he thought everything was taken care of.”

The delivery of Thomas’ unpreserved body seems to have had a significant effect on the Burpee family. Adeline, says Trenholm, was “horrified at what happened,” and expressed this in a letter to the army chaplain.

Though Charley would have had scant memories of his father, both sons became advocates for the memory of Thomas Burpee. “There’s a lot in the collection where they’ve written, talking about their father, or doing things in their father’s memory,” Trenholm says. “It was very, very strong in them, that they needed to keep his memory alive.”

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook