How a Gift from Schoolchildren Let the Soviets Spy on the U.S. for 7 Years

Attention, ambassadors: inspect every present carefully.

The Great Seal that held a listening device. (Photo: NSA/Public Domain)

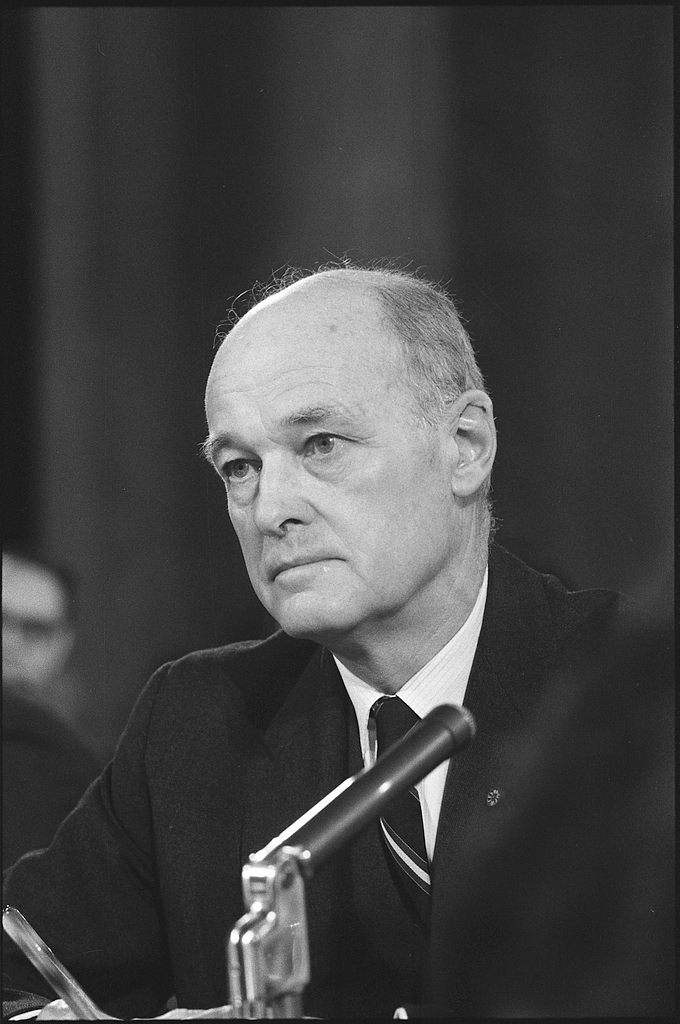

In 1946, a group of Russian children from the Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organisation (sort of a Soviet scouting group) presented a carved wooden replica of the Great Seal of the United States to Averell Harriman, the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union.

The gift, a gesture of friendship to the USSR’s World War II ally, was hung in the ambassador’s official residence at Spaso House in Moscow. It stayed there on a wall in the study for seven years until, through accident and a ruse, the State Department discovered that the seal was more than a mere decoration.

It was a bug.

The Soviets had built a listening device—dubbed “The Thing” by the U.S. intelligence community—into the replica seal and had been eavesdropping on Harriman and his successors the whole time it was in the house. “It represented, for that day, a fantastically advanced bit of applied electronics,” wrote George Kennan, the ambassador at the time the device was found. “I have the impression that with its discovery the whole art of intergovernmental eavesdropping was raised to a new technological level.”

Diplomats and other Americans working in the USSR had long assumed that the walls in Moscow had ears. “Russia’s notoriety for eavesdropping and espionage stretches back even to the czars,” Representative Henry J. Hyde told the House of Representatives toward the end of the Cold War. “James Buchanan, U.S. minister in St. Petersburg during 1832-33 and later U.S. President, recounted that ‘we are continually surrounded by spies both of high and low degree. You can scarcely hire a servant who is not a secret agent of the police.’”

In the early 20th century, human espionage and eavesdropping was augmented by new technology like wiretaps and small, concealable listening and recording devices. Guests at Spaso House were given cards on arrival warning them that all rooms and even the garden were monitored. The Thing was one of the most sophisticated of these bugs. It was designed by Lev Sergeyevich Termen, better known to Americans as Leon Theremin, inventor of the theremin. Theremin had lived in the US for a while, but returned home to Russia just before WWII when he ran into financial problems. There, Theremin was sent to prison for “rehabilitation” and eventually put to work in a sharashka (a secret lab in the Gulag labor camp system), tasked with finding a better way to bug Spaso House.

Spaso House, the U.S. Ambassador’s official residence in Moscow and home to “The Thing” for seven years. (Photo: US Government/Public Domain)

The device he came up with consisted of an antenna and a cylinder with a thin membrane that acted as a microphone. Soviet agents stationed across the street from Spaso House would turn the device “on” by focusing a radio signal on it, which then bounced back to their radio receiver. When the ambassador or anyone else in the study spoke, the sound waves caused the membrane to resonate and alter the signal that returned to the Soviets, allowing them to hear the conversation.

“The triumph of the Great Seal Bug was its simplicity,” said Robert Brown in his book on early technical surveillance, Electronic Invasion. “It had no power pack of its own, no wires that could be discovered, no batteries to wear out,” and was active only when the Soviets “illuminated” it with a radio signal, making it nearly impossible to detect.

The State Department only became suspicious that the Soviets had developed this novel bug in the early 1950s, when British and American military radio operators monitoring Soviet military radio traffic independently and accidentally picked up the voices on their receivers that appeared to belong to their respective diplomats.

Those incidents and the refurbishing of Spaso House by Soviet workers for ambassador George Kennan’s arrival in 1952—a perfect opportunity to plant devices—led to several security sweeps of the house, which turned up nothing.

“The air of innocence presented by the walls of the old building was so bland and bright as to suggest either that there had been a complete change of practice on the part of our Soviet hosts (of which in other respects there was decidedly no evidence) or that our methods of detection were out of date,” Kennan wrote in his memoirs.

George Kennan, former Ambassador to the Soviet Union, in 1966. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-07025)

In case the latter was true, State Department security technicians John Ford and Joseph Bezjian arrived in Moscow in September to conduct a more thorough search. Bezjian, nicknamed the “the Rug Merchant” by his colleagues, suspected that the Soviets had removed their bugs prior to the other sweeps and replanted them when the coast was clear. To keep them from doing that again, he posed as Kennan’s house guest. He had his equipment sent, well hidden, ahead of his arrival and spent several days hanging out, playing cards and observing the house staff while hunting for bugs at night. When they still couldn’t find anything, Ford and Bezjian suggested that they might have more luck if Kennan gave the eavesdroppers something to listen to.

One evening, the ambassador sat in the study with his secretary, going through the motions of dictating a classified diplomatic dispatch (actually one that had already been sent years ago, declassified and printed in a volume of the Department of State’s Foreign Relations of the United States series), while Ford and Bezjian went around the house with their detection instruments.

Kennan recounts in his memoirs that as he “droned on with the dictation,” Bezjian picked up Kennan’s voice on his radio receiver and followed the signal to its source. Bezjian went to the study and implored Kennan, “by signs and whispers, to ‘keep on, keep on.’” He left to grab Ford and the two men returned to work their way around the room. The signal carrying Kennan’s voice appeared to be coming from the wall behind the seal. Bezjian removed the wood carving, Kennan wrote, “took up a mason’s hammer, and began, to my bewilderment and consternation, to hack to pieces the brick wall where the seal had been.” As he did this, the signal cut out. Bezjian realized that the bug wasn’t in the wall but in the seal, and took his hammer to the Soviets’ gift.

“I, continuing to mumble my dispatch, remained a fascinated but passive spectator of this extraordinary procedure,” Kennan wrote. “In a few moments, however, it was over. Quivering with excitement, the technician extracted from the shattered depths of the seal a small device, not much larger than a pencil.”

A replica of the inside of the Great Seal Bug, showing the listening device. (Photo: Austin Mills/CC BY-SA 2.0)

At this revelation, wrote Kennan, “one was acutely conscious of the unseen presence in the room of a third person: our attentive monitor. It seemed that one could almost hear his breathing. All were aware that a strange and sinister drama was in progress.”

That night, Bezjian slept with the bug under his pillow so that Soviet agents couldn’t retrieve it. The next day, it was sent to Washington to be studied and replicated by American intelligence agencies, kicking off an arms race between the Soviets and Americans to develop similar and improved versions of the bug and countermeasures against them.

In the years The Thing hung on the wall, Spaso House was full of activity, high-level guests — including General Eisenhower, White House staffers and a dozen congressmen — and information. A member of the Soviet team that monitored the house via The Thing later revealed that it allowed them to “get specific and very important information which gave us certain advantages in the prediction and performance of world politics in the difficult period of the cold war.”

Whatever information the Soviets may have gained from The Thing, the wooden eagle would ultimately come back to bite them. In May 1, 1960, the Soviets shot down an American U-2 plane over Soviet airspace. At a meeting of the United Nations Security Council later that month, they accused the United States of spying and drafted a resolution to condemn the U-2 flights as aggressive acts and stop them. After sitting through several days of verbal attacks from the Soviets, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the U.S. Ambassador to the UN, countered by displaying the replica seal and the bug inside for the Security Council and the press as proof that the Soviets were also spying on Americans. The next day, the Soviet resolution was defeated 7-2.

Khrushchev inspects the wreckage from the U-2 spyplane, 1960. (Photo: US Government/Public Domain)

As tense and weird as the discovery of The Thing was, George Kennan said that having the listening device in his home also provided some amusement in hindsight. He recalled that when he first moved into Spaso House, he often practiced his Russian by reading aloud to himself in the bugged study. He looked for material that covered events and people relevant to world politics and diplomacy, and the scripts for Voice of America broadcasts, full of “vigorous and eloquent polemics against Soviet policies,” fit the bill.

“I have often wondered what was the effect on my unseen monitors, and on those who read their tapes, when they heard these perfectly phrased anti-Soviet diatribes issuing in purest Russian from what was unquestionably my mouth, in my own study, in the depths of the night,” Kennan wrote. “Who, I wonder, did they think was with me? Or did they conclude I was trying to make fun of them?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook