Bram Stoker Wrote in His Library Books

The London Library combed through its shelves to track down his marginalia.

Bram Stoker never traveled to Transylvania. But, while researching and drafting Dracula, he seems to have made frequent trips to the London Library.

There, books transported Stoker to the region in the Carpathian Mountains, and he brushed up on geography, cuisine, and superstitions. He also apparently left his mark on some of the library’s volumes.

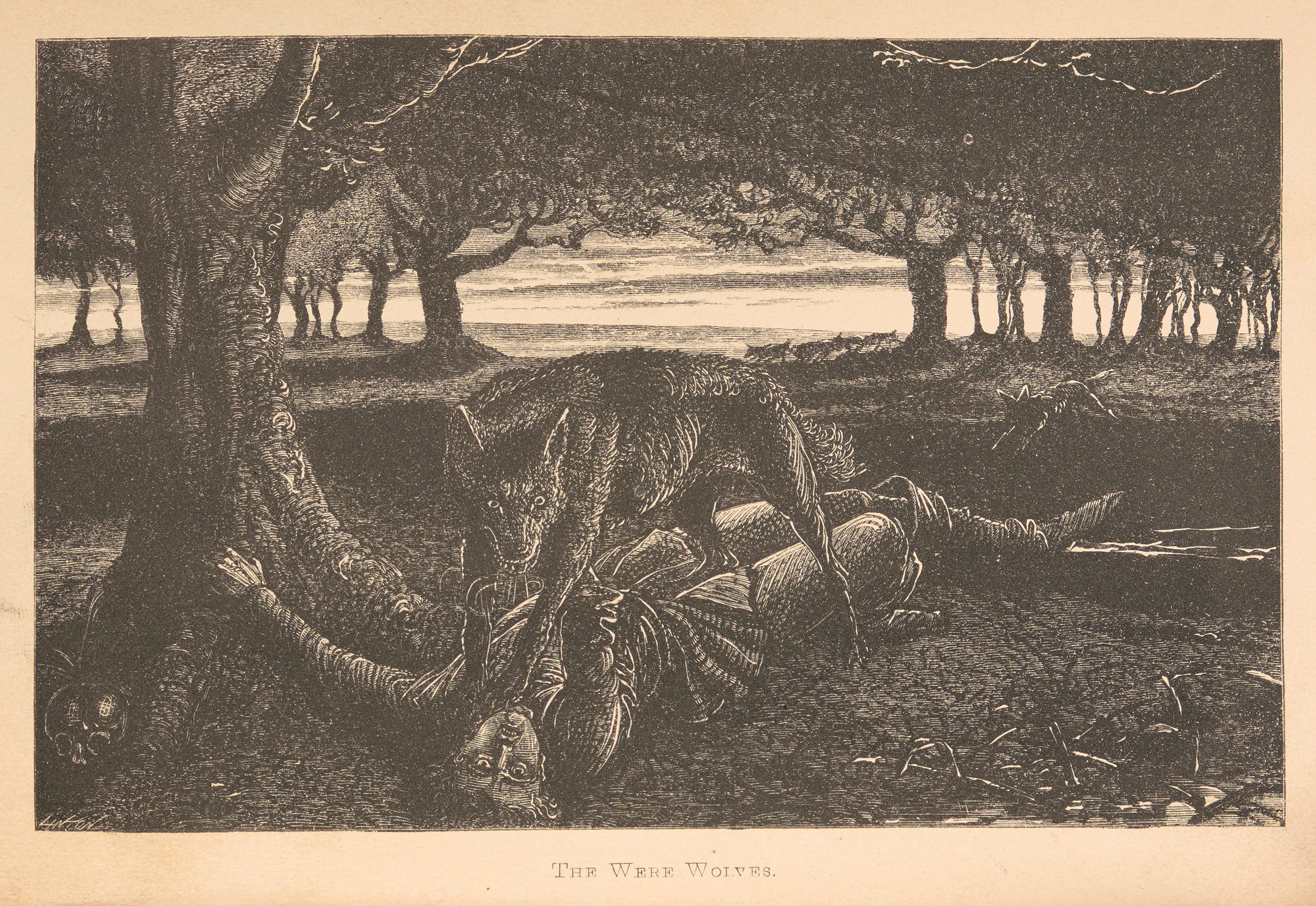

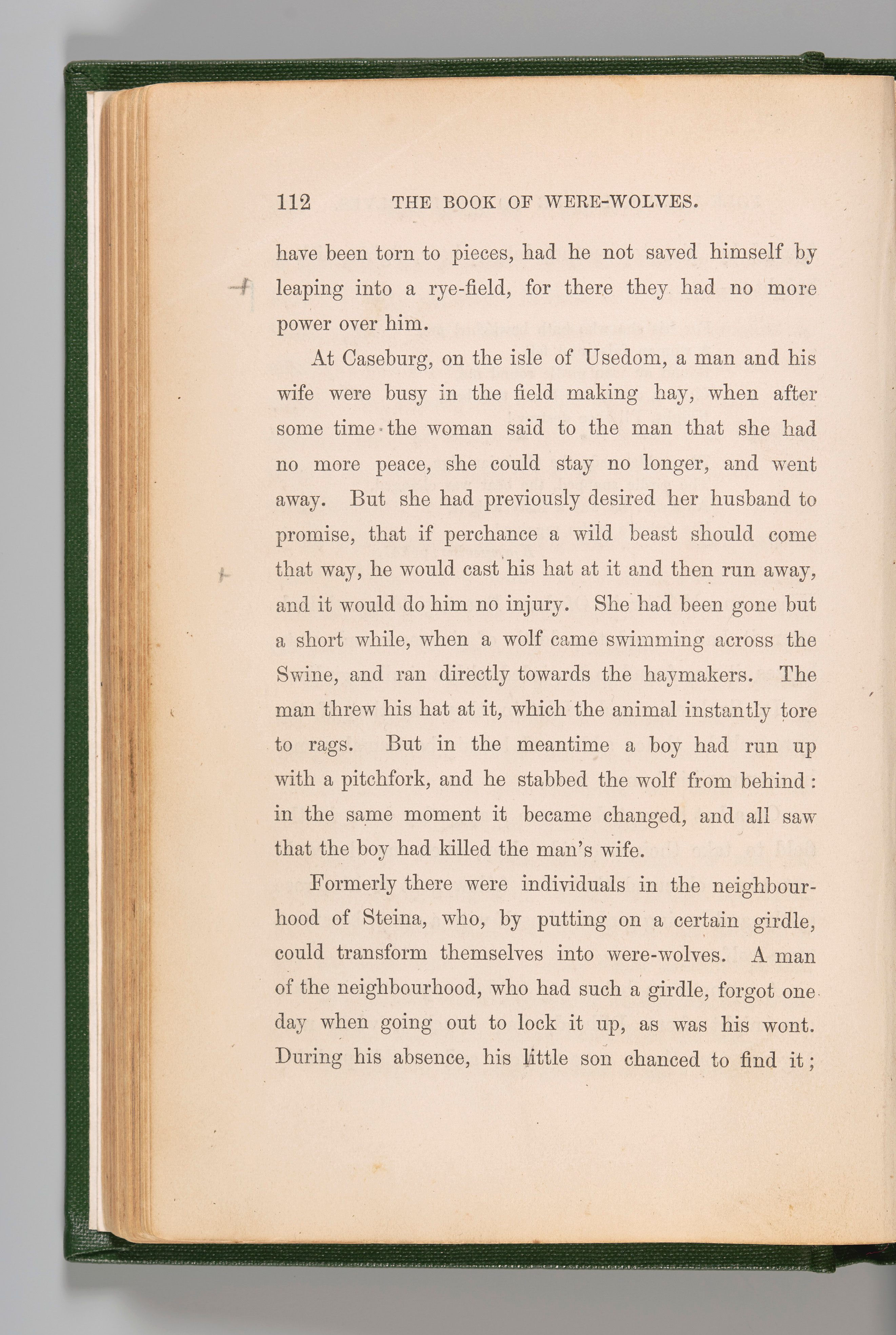

Stoker applied for library membership in 1890, seven years before he published his vampire novel. As he leafed through the books, Stoker took meticulous notes. That’s how scholars know that he perused The Book of Were-Wolves, in which Sabine Baring-Gould relates the tale of a lycanthrope “big as a calf against the horizon, its tongue out, and its eyes glaring like marshfires.” To conjure the picture of lonely castles at the top of jagged hills, Stoker turned to books such as An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. Stoker’s notes were rediscovered in 1913; in 2008, the scholars Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller compiled them into a book, Bram Stoker’s Notes for Dracula. When the library’s development director, Philip Spedding, saw this volume, he decided to work backwards and see which of the books Stoker referred to were still in the collection.

Spedding found 26 of them, and many bear annotations that jibe with Stoker’s notes. The marginalia mainly consist of lines, crosses, and dog-eared pages—the sort of marks you might make in a textbook if you’re cramming for a quiz.

There’s very little handwriting on the books’ pages—and where there is, “it is more difficult to confirm that this is Stoker,” writes Julian Lloyd, the library’s head of communications, in an email. “Occasional comments are not recorded in the Notes for Dracula in the way the marginalia is (where he identifies specific passages and then puts exact pencil markings against them).”

Regardless, the library’s staff now believes that Stoker’s Transylvania tale has roots in London. “It is not fanciful to suggest that his extraordinary tale of the Transylvanian undead has many of its origins in the quiet confines of St. James’s Square,” Spedding said in a news release. Now that the word is out, the library has removed the books from open shelves, lest they tempt souvenir seekers. “We’ve now put the books in our safes,” Lloyd writes.

While we’re not suggesting that you emulate Stoker’s scribbles in library books of your own, the little scratches are a fun reminder of the way that books open worlds to readers—and help writers create entirely new ones.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook