How Did a Shark in a Sydney Aquarium End Up With a Human Arm?

It opened its mouth and a murder mystery came out.

In 1935, a shark on display in an Australian aquarium vomited up a human arm.

In a regular shark attack story, this would be the happy ending, with the beast captured and at least part of its victim’s body recovered so it could be laid to rest.

But this is no ordinary shark tale. The shark, it turns out, didn’t attack anyone. It wasn’t the villain, but more like the jogger in a Law and Order episode who discovers a body and sets the story in motion. Its bout of indigestion was just the beginning of a murder investigation and one of Australia’s most infamous crime stories.

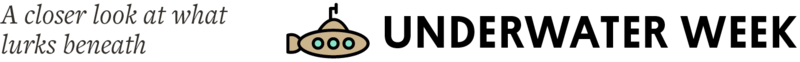

The 14-foot tiger shark had been caught in mid-April off Coogee Beach in Sydney by a local fisherman named Bert Hobson after it got tangled in the line while eating a smaller shark that Hobson had hooked. He and his son hauled the fish to shore and brought it to the Coogee Aquarium and Swimming Baths, run by Hobson’s brother, for exhibition. After a few days in which it seemed to adjust to its new home, the shark became irritable and began behaving erratically. It repeatedly rammed the walls of its tank before sinking to the bottom and swimming in lazy, irregular circles.

Finally, it began to vomit. According to a reporter from the Sydney Morning Herald who was there to write about the new display, a “copious brown froth which smelled really foul” issued from the shark’s mouth and a “bird, a rat, a load of muck and human arm with a piece of rope tied around it” floated to the surface.

The police were called, and the coroner and a shark expert examined the arm. They concluded that it had not been bitten off—there were no tooth marks anywhere and the limb had been cleanly removed at the shoulder with a blade. The police started a homicide investigation and allowed a local newspaper, Sydney’s Truth, to print a description and picture of a tattoo found on the arm’s bicep in hopes that someone would come forward with information.

Coogee Beach, Sydney, in 1936. The tiger shark was captured off this beach. (Photo: Royal Australian Historical Society/Public Domain)

A man recognized the tattoo, an image of two boxers squaring off, and identified the arm as belonging to his brother James Smith, a bookie, amateur boxer and small time crook who had gone missing a few weeks earlier.

Detectives quickly pieced together Smith’s most recent activities. He was last seen alive at hotel in the Sydney suburb of Cronulla drinking and playing dominoes with his friend Patrick Brady, who had rap sheet full of forgery convictions.

As the investigation continued, it became clear that the two friends’ night out had taken a bad turn. Brady’s landlord told police that Brady had vacated his rented bayside cottage shortly after Smith went missing, and before the lease was up. When the landlord inspected the place, he found that a mattress and trunk had been replaced, the walls had been cleaned and a rowboat included with the cottage had been scrubbed.

With Brady, the police had a suspect, and they soon found a motive. A cab driver told the investigators that the day after Smith was last seen, he’d driven Brady—who looked disheveled and nervous—to north Sydney and dropped him off outside a house belonging to Reginald Lloyd Holmes.

Holmes was a respected boatbuilder and businessman, but also deeply involved in Sydney’s criminal underworld. He controlled a smuggling ring and sometimes employed Smith and Brady to take his business’s speedboats out to pick up cocaine, cigarettes and other contraband thrown overboard by passing ships. He also orchestrated insurance scams in which Smith and Brady intentionally sank or set fire to his boats so he could get the insurance money. The detectives figured that after one of these frauds had gotten botched and the insurance company refused to pay out, the conspirators had a falling out and one of the men had murdered Smith.

Both Brady and Holmes were brought in for questioning, but refused to cooperate. While Brady was charged with the murder and further pressed for a confession, Holmes, who claimed to not know Brady or Smith, was released.

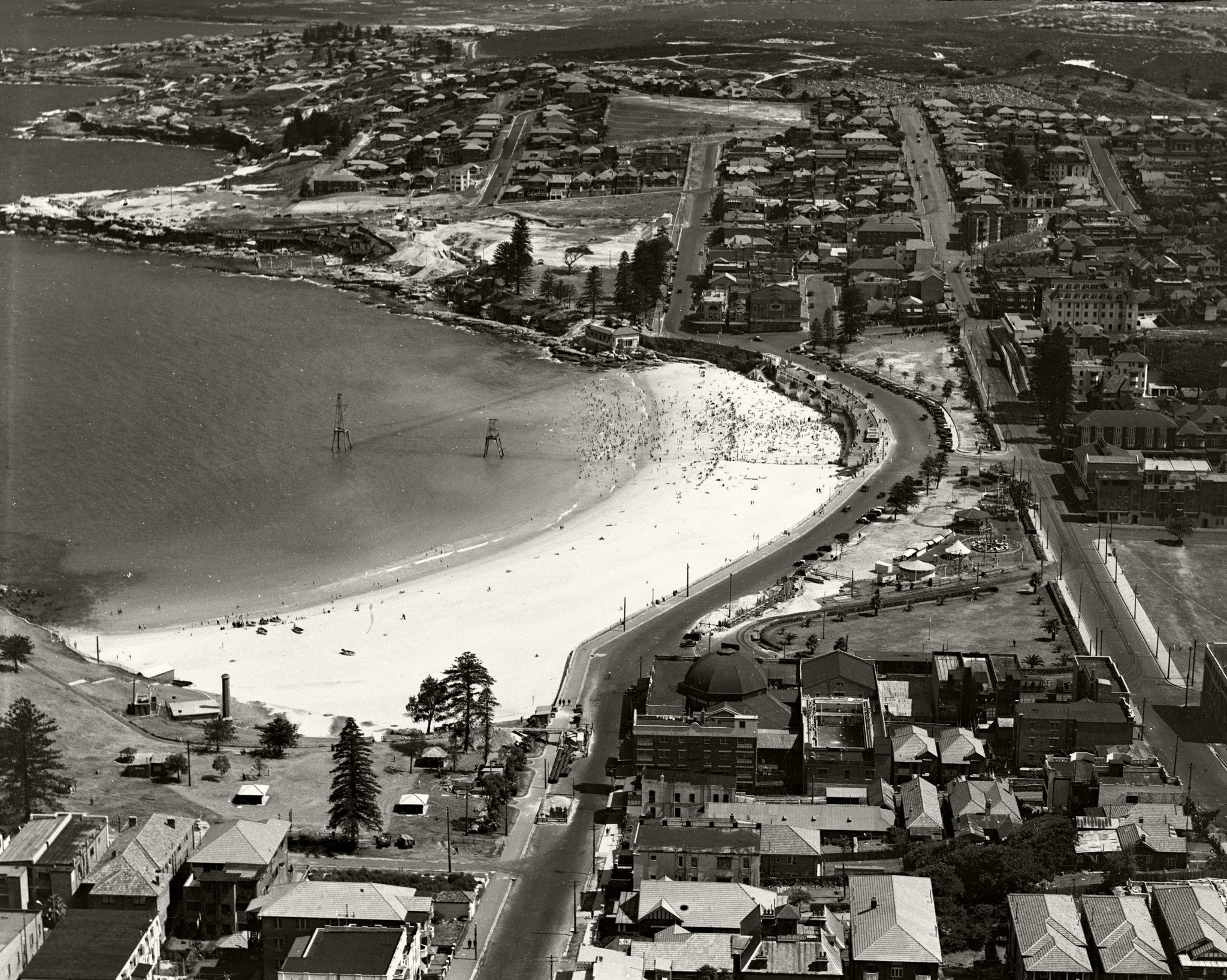

A few days later, Holmes took one of his speedboats out into Sydney’s Lavender Bay, shot himself in the head and fell into the water. He only managed to wound himself, though. The small caliber bullet had flattened against his forehead and merely stunned him. The fall into the water revived him and he climbed back into the boat, only to find that onlookers had called the police. He led police boats on a hours-long chase around the bay, through Sydney Harbor and out toward the ocean, where he finally gave up and let the cops take him to the hospital.

Miller’s Point, near the Sydney Harbor Bridge and close to where Reginald William Lloyd Holmes was found shot. (Photo: Royal Australian Historical Society/Public Domain)

After recovering from his wound, Holmes was ready to talk. At first he tried to explain away his suicide attempt and the boat chase by saying he’d been attacked and shot in his home, fled in the boat and mistook the police for his assailants. Eventually, he claimed that Brady had murdered Smith at the cottage, dismembered the body and buried most of it at sea in a trunk (which would explain the missing items and cleanup). He kept the one arm, though, and brought it to Holmes’ house, threatening that Holmes would wind up like Smith if he didn’t pay Brady off. Afterwards, Brady tied a weight to the arm and threw it into the water where it was swallowed by the shark, and Holmes suffered a nervous break and decided to kill himself on the boat.

Holmes agreed to repeat all this in court, but the night before the trial began, he was shot dead in his car. The crime scene and Holmes’ recent behavior suggested suicide, but his impending testimony pointed towards murdering him to keep him quiet. Legal historian Alex Castles argued another explanation in his book about the case: that Holmes took out a hit on himself. That would’ve spared his family any embarrassment if his own crimes were revealed during the trial, and also allow them to collect on his life insurance, which might not have paid out if he committed suicide.

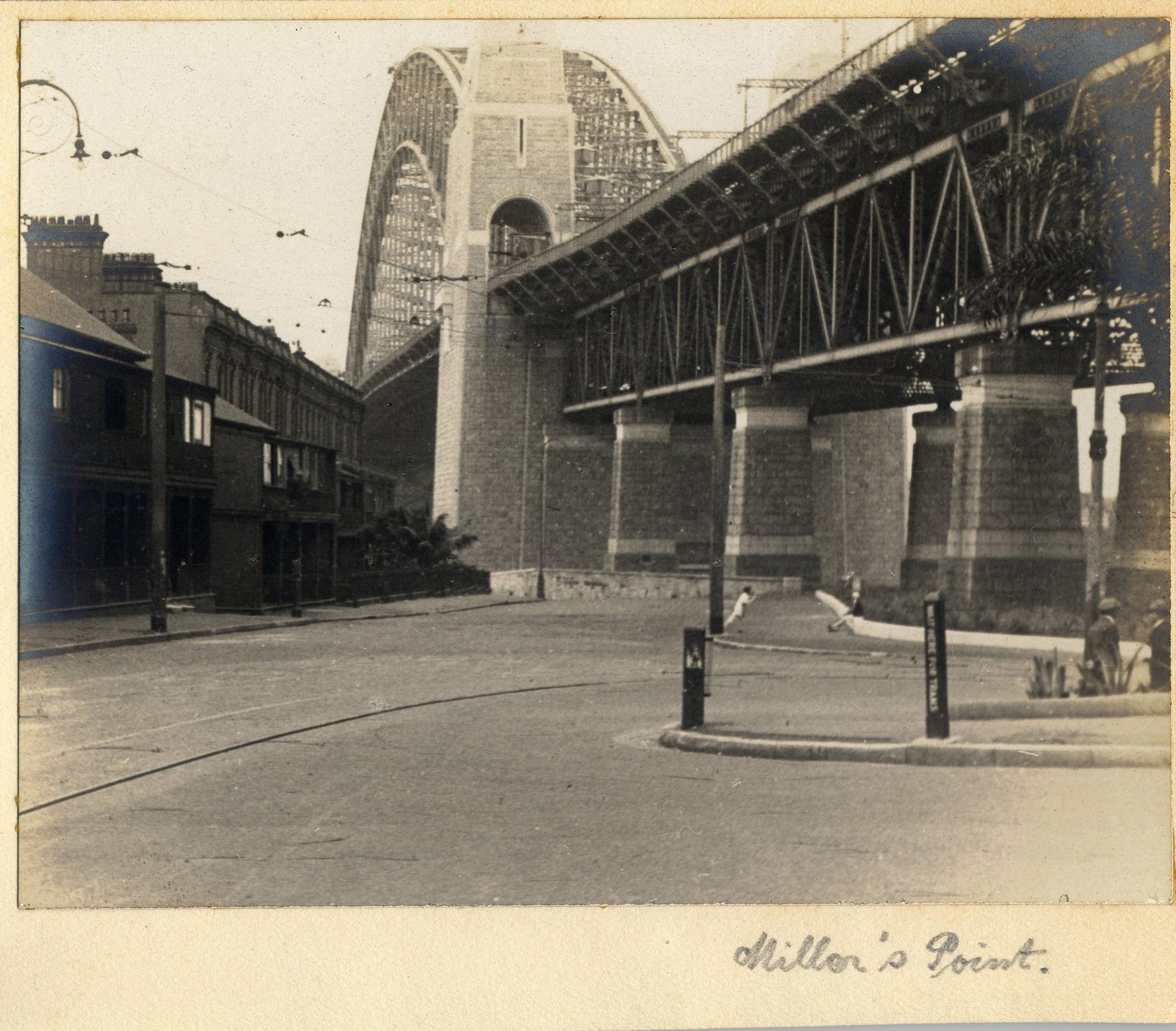

The coverage of the trial The West Australian newspaper on Tuesday September 10, 1935. (Photo: National Library of Australia)

With Holmes dead, the case against Brady fell apart. His lawyer argued all the other evidence was circumstantial and, more importantly, that an arm was not a body and with no body there was no homicide. A one-armed Jim Smith could still be alive somewhere, the defense said. The judge agreed and directed the jury to acquit. Brady was freed, but arrested on forgery charges as soon as he walked out of the courthouse. He maintained his innocence in the murder until his death in 1965.

Smith’s murder was never solved, but Castles suggested that Smith was a police informant (charmingly known as a “fizgig” in early 20th-century Australian slang) and was killed by bank robber Eddie Weyman after Smith provided info that led to his arrest.

As for the shark, it was killed and opened up in a search for more of Smith’s remains, but like the man whose arm it swallowed, the fish’s days as an informant were done.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook