The Less-Than-Effective Shark Nets Protecting Australia’s Beaches

Can a strip of mesh really keep great whites away?

Swimmers at shark-netted Bondi Beach in Sydney. (Photo: Tim Grubb/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Gaze over the sprawling mass of humanity toward the horizon from any popular Sydney beach in summer and, if you’re eagle-eyed, you may be able to spot the shark net buoys.

Located around 1,600 feet from the shore, these bobbing markers secure the shark-deterring mesh nets that have been in use since 1937. A minor detail: those shark nets may not work.

Mesh nets were introduced to beaches in New South Wales—the state that’s home to Sydney—in 1937. At the time, the state government was preparing to host international visitors to commemorate the 150-year anniversary of British colonization. Concerned that one of these visitors might encounter a shark during an aquatic frolic, the government installed nets at 18 beaches in the state, including at the famed Bondi Beach.

Preparing a shark net at Stockton beach, circa 1950. (Photo: State Library of NSW)

Three months later, a man was attacked by a shark at one of those netted beaches. Ernest Baker was paddling a long, narrow kayak known as a surf-ski at Cronulla Beach in Sydney’s south when he felt “a terrific bump.” The force of the impact threw him into the water. When he surfaced, said a news report at the time, “he was terrified to see a huge shark on the other side of the overturned surf-ski.” Baker was shaken but uninjured, though his surf-ski, “when brought ashore, was found to have deep indentations on the upper and lower sides, such as would be made by the teeth of a shark.”

In the decades since Baker got knocked off his surf-ski, says Natalie Banks, National Campaign Director at conservation organization Sea Shepherd Australia, there have been about 40 shark “encounters” among the now-51 netted New South Wales beaches, “including a fatality and some very serious bites.”

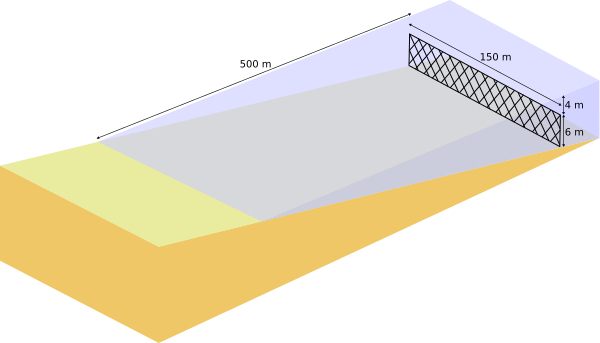

Placed within 500 meters (1,640 feet) of the shore, the nets, which measure around 500 feet wide and 20 feet tall, are intended to function as deterrents, not barriers. “What they’re trying to do is capture sharks to stop them from actually getting to the popular beaches where there are bathers,” says Banks. “However, the majority of sharks have been found on the opposite side of the shark net—on the shore side.”

A diagram of the type of shark net found at New South Wales beaches. (Image: DennisM/Public Domain)

In February, Deakin University environmental science professor Laurie Laurenson claimed that an analysis of 50 years of data on shark mitigation programs showed the nets “do nothing.” But faith in them—among the public, the government, and some scientists, remains high. In response to Laurenson’s claim, shark expert Dr. Barry Bruce said nets “certainly reduce risk because they catch and kill sharks that have the potential to bite people.”

This killing of the sharks—and of other marine animals unlucky enough to get enmeshed—is another big factor in the net debate. Shark nets, says Banks, “are a fishing device, and they will catch and kill, or entangle, anything that gets caught.” Turtles, rays, dugongs, seals, and even whales are among the animals who end up ensnared.

It’s an issue that inspires impassioned responses. In 2012, Sydney newspaper the Daily Telegraph claimed “radical conservationists” had been slicing holes in the shark nets of local beaches. A rep from the environmentally-focused Greens political party responded by calling the nets “indiscriminate killers of harmless marine life” that are “next to useless in preventing attacks anyway.”

There are shark-deterring options beyond the current style of nets, including aerial surveillance programs, plastic “eco-shark” barrier nets that don’t entangle wildlife, and Clever Buoys, which are sonar-equipped floats that scan for sharks in the area. Such alternatives, along with tagging and tracking sharks and the development of a shark safety app, are part of the New South Wales government’s current five-year, $12 million Shark Strategy.

A rare enclosed-style shark net at Nielsen Park in Sydney. (Photo: Aidan Casey/CC BY-ND 2.0)

One element that is less manageable is public fear. “Our media plays on fear of sharks, and the idea that you can be taken by these snapping monsters of the oceans who are lurking every time you put your big toe in the water,” says Banks.

Shark nets may be less effective than people think, but “it’s so difficult to get that message across, because it’s people’s fears that you’re talking about, or talking to.”

For now, the nets remain in place at New South Wales beaches, but the trialing of new shark detection systems—including Clever Buoy, described as “facial recognition technology for marine life“—points toward a future in which they may no longer be needed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook