The Illegal Ramen Vendors of Postwar Tokyo

Black markets and American wheat imports popularized ramen.

When Japan surrendered in the Second World War, the country was in a state of ruin. Bombers from the United States had either destroyed or damaged over two million buildings, causing hordes of hungry Japanese citizens to be increasingly reliant on black markets for food. Within these sprawling urban black markets, ramen emerged as a critical part of Japanese cuisine.

Ramen was first introduced to Japan by Chinese immigrants in the late 19th century, according to Japan Quarterly, and originally consisted of noodles in broth topped with Chinese-style roast pork. In December 1945, Japan recorded its worst rice harvest in 42 years. Combined with the loss of agriculture from its wartime colonies in China and Taiwan, it drastically reduced rice production—which is how a bowl of wheat noodles gained prominence in Japan’s rice-based culture.

Following Japan’s defeat in the war, the American military occupied the country from 1945 to 1952. Faced with this food shortage, the Americans started to import massive amounts of wheat into Japan. From 1948 to 1951, bread consumption in Japan increased from 262,121 tons to 611,784 tons. But wheat also found its way into ramen, which most Japanese ate at black market food vendors. Black markets had existed in Japan throughout the war. However, they became increasingly essential during the last years of the war and throughout this period of occupation. With the government food distribution system running about 20 days behind schedule, many people depended on black markets for survival.

By October 1945, an estimated 45,000 black market stalls existed in Tokyo. The city was also home to the most famous black market in Japan, Ameyokocho. Located underneath an active train line in the center of the city, it was packed with open-air stalls selling everything from candy to ramen and clothing. In this bustling environment, vendors announced their presence with the distinctive sound of charumera flutes and sold ramen from a yatai, a wheeled food cart filled with drawers containing noodles, pork slices and garnishes, alongside pots of boiling soup and water. Prices were also low due to the abundance of American wheat and lard.

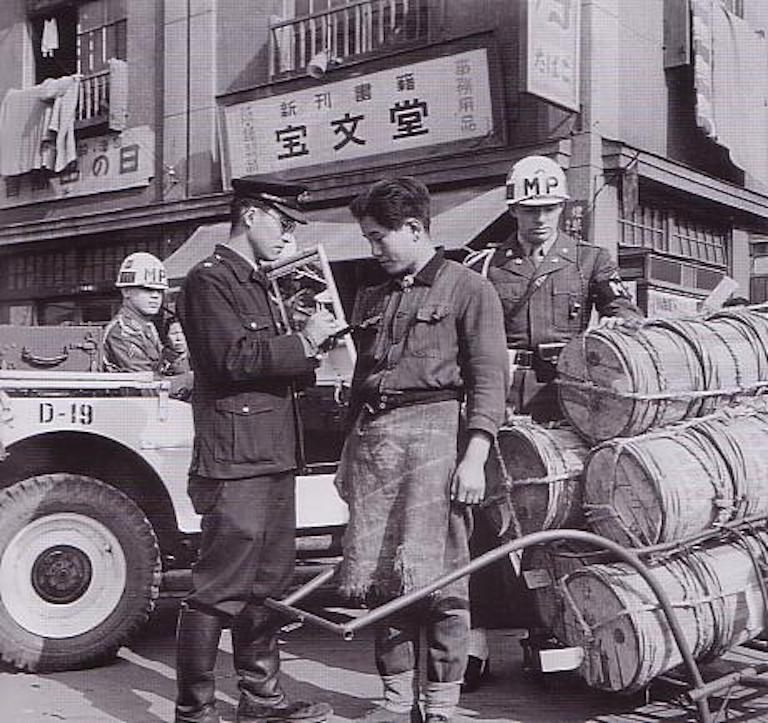

At the time, it remained illegal to buy or sell restaurant foods during this period of occupation. This was due to the Americans maintaining Japan’s wartime ban on outdoor food vending, which had been implemented by the Japanese government to control rationing. So flour for ramen was secretly diverted from flour milling companies into the black markets, where nearly 90 percent of street stalls were under the control of the yakuza, who extorted the vendors for protection money. Thousands of ramen vendors were arrested during the occupation.

But by 1950, the government started to loosen its restrictions on food vending and removed controls on the exchange of wheat flour, which further boosted the number of ramen vendors. Corporations even rented out yatai starter kits for vendors, complete with noodles, toppings, bowls, and chopsticks.

Unlike the countless variations that exist today, ramen during this period was simple. According to Jonathan Garcia, a ramen class instructor at Osakana in Brooklyn, New York, ramen during this time was a shoyu (soy sauce) based soup, made from a combination of pork, chicken, and niboshi (dried sardines). The seasoning was mixed into the pot of soup, and vendors would replenish it throughout the day. These days, ramen is seasoned individually by bowl with shoyu or other ingredients before being combined with soup.

Foods rich in fat and strong flavors became known as “stamina food,” according to Professor George Solt, author of The Untold History of Ramen. Ramen was very different than the milder, seaweed-based noodle soups of traditional Japanese cuisine. Okumura Ayao, a Japanese food writer and professor of traditional Japanese food culture at Kobe Yamate University, once expressed his shock at trying ramen for the first time in 1953, imagining “himself growing bigger and stronger from eating this concoction.”

The Americans also aggressively advertised the nutritional superiority of wheat and animal protein, endowing ramen with a nutritious reputation and a welcome change for a population weary of rationing. And in a failing economy, running a ramen yatai was one of the few opportunities where small business entrepreneurship was still possible. Gradually, ramen became associated with urban life, eaten by the working class huddled around a yatai in a bombed-out city.

Ramen is arguably Japan’s most popular food today, with Tokyo alone containing around 5,000 ramen shops. But the past combination of economic necessity, American wheat, and Chinese culinary influence propelled ramen into the mainstream, and in turn, forever changed the way Japan ate.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook