How Massachusetts Came to Have Its Own Bermuda Triangle

The story behind some very mysterious rocks.

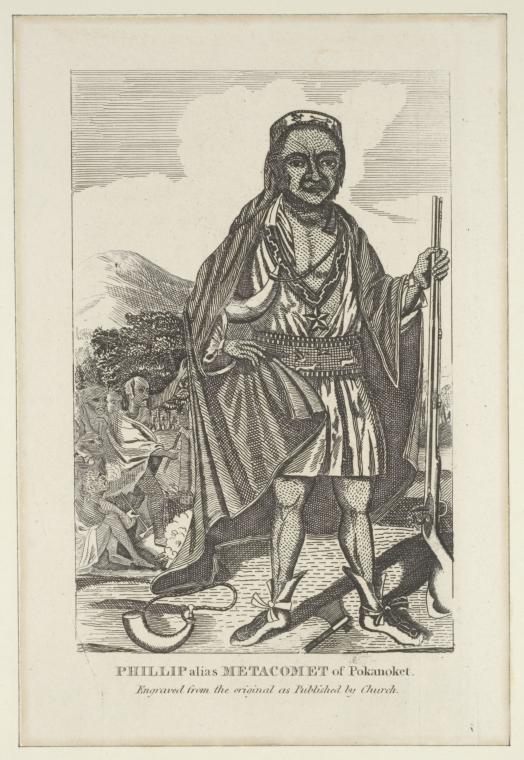

The spot isn’t easy to find. Only by crab walking across stones and ducking under the rock that forms the ceiling of King Philip’s Cave can you rest in the spot where Metacomet, chief of the Massachusetts Wampanoag, likely spent one of his final nights. The leader was slaughtered by one of his own men and beheaded by English settlers in 1678 in a war that pitted the Algonquin nations against the white settlers.

In such a lovely spot, you almost forget you are in a quiet neighborhood full of upper middle-class houses in the quiet Boston suburb of Norton, Massachusetts. But there’s an undeniable chill in the air. The rock formation is one of many such sites in a 200-square-mile area of Southeastern Massachusetts that locals and paranormal enthusiasts call the “Bridgewater Triangle.”

That’s right: a mystical swamp zone within commuting distance of Boston.

For centuries, locals have reported strange activity in and around the swamp: from Bigfoot sightings to ghosts, strange orbs that weave through the trees, UFOs, unmarked black helicopters, satanic rituals, and cattle mutilation. In 1980, Boston Magazine reported that police sergeant Thomas Downey spotted a six-foot-tall winged creature while driving late at night on a country road. Some paranormal aficionados asserted that this was the mythical Thunderbird, prominent in local Indigenous mythology. Around the same time, famed cryptozoologist and folklorist Loren Coleman brought wider attention to the area and its spooky reputation in his bestselling book Mysterious America. In it he traced an area from Abington to Rehoboth and Freetown, encompassing the swamp and the surrounding towns, delineating the invisible borders of the triangle for the first time.

The Hockomock Swamp, an enormous swath of marshland that comprises the single largest freshwater basin in all of Massachusetts, was the final holdout for Metacomet and his warriors in the days leading up to their annihilation by the English. By the end of King Philip’s War, nearly 3,000 Wampanoag men, women, and children were killed or sold onto slave ships bound for the West Indies. The landscape is dotted with stone monuments to their lives here. Their ghosts have morphed over centuries into foreboding fairytales of fantastic creatures and fanged entities that tell us more about the ancestral guilt and paranoia of the conquerors than the natives themselves. At Profile Rock in Freetown, a natural granite formation resembling a human face watches over the woods. Locals claim the natives believed the face to be an image of Chief Massassoit, Philip’s father, who was friendly to the newly arrived English. Today, crude graffiti mars the walls of the sacred cliff face.

A few miles away, in the hamlet of West Bridgewater at the base of a wooden bridge is hidden the Solitude Stone. Lost for nearly a century beneath moss and overgrowth, the stone bears a 150-year-old inscription thought to be carved by Reverend Timothy Otis Paine of the New Church of Jerusalem, a Christian sect founded on the principles of occultist Emmanuel Swedenborg, whose philosophies purportedly influenced Freemasonry. In his doctrine of correspondences, Swedenborg asserted that the physical world was the result of spiritual causes and the laws of nature were reflections of spiritual laws. The mysterious inscription reads:

All ye, who in future days,

Walk by Nuckatesset stream

Love not him who hummed his lay

Cheerful to the parting beam,

But the Beauty that he wooed,

In this quiet solitude.

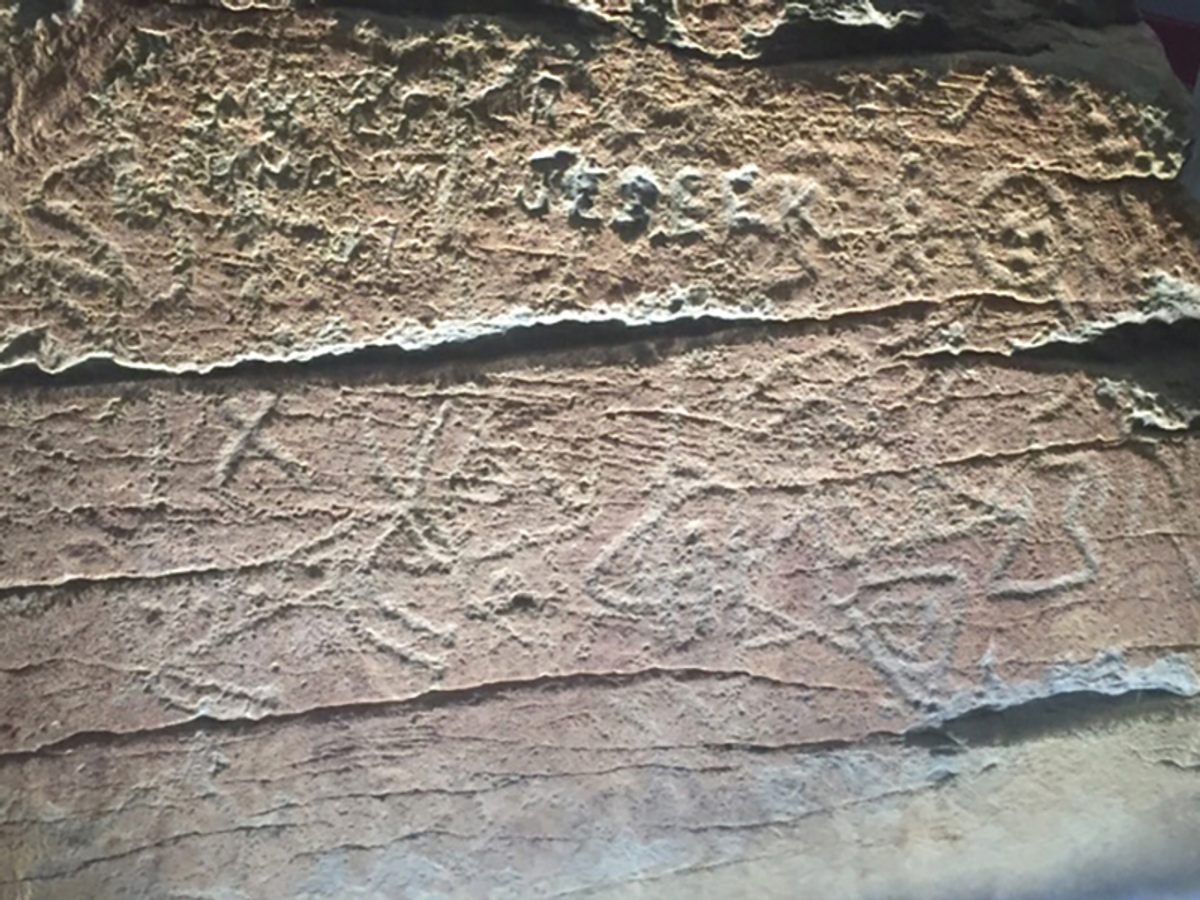

Perhaps the most interesting spot in this area is the Dighton Rock. People of unknown origin carved figures of people, animals, and symbols into the flat side of this trapezoidal boulder roughly the size of a small Volkswagen. The origin and meaning of the markings has been the subject of debate for centuries, with theorists attributing the petroglyphs to peoples as various as ancient Native Americans, Phoenicians, Norse, colonial Portuguese, and even medieval Chinese sailors. In the 1950s the stone was removed from the river by crane and deposited on the shore, where a museum was built up around it. Today, a small but knowledgeable fellowship of local citizens runs the museum and even organizes lectures exploring the history of the area and the theories surrounding the stone and its markings.

The museum is open for self-guided tours by appointment only. On this particular day, I had not called for an appointment. Crestfallen, I was ready to quit the woods when I encountered two women, one strolling, one rolling heartily in her electric wheelchair along the wooded road, who told me they were Friends of the Dighton Rock Museum, and that they happened to have a key. They were kind enough to help me set up an appointment with the park service. The woman in the wheelchair didn’t buy the single-origin humdrum. “Personally, I think it’s from a multiplicity of cultures.” I agreed to meet them the next morning.

The next day, I was allowed to spend an hour with the stone. Indeed, the markings seem to signal a mishmash of cultures, with geometric shapes and humanoid figures that recall Paleolithic paintings from Australia and Central Africa, as well as formally striking representations of a deer and a seal. These primordial images commingle with etchings that appear almost modern, with a Roman letter “R” and “F” clearly defined at the center of the stone, which may very well be colonial graffiti but which has inspired theories that the markings are proof that lost Portuguese explorers, or even Vikings, made it to the New World.

One theory from the 1700s states that ancient Phoenicians, after making it to New England shores, engraved the stone with images from their cosmogony, with the past, present, and future represented simultaneously in symbol-strewn vignettes that bleed into one another on the tide-facing side of the stone. If you look closely, you can find the most recent carving: a signature made in the 1920s by a guy named Jesse. The Friends of the Dighton Rock Museum, although careful to preserve an air of suspended judgment, cannot help but offer their own theories. The human figure on the left, they say, is a symbol of femininity and fertility. The symbol resembling an “X” with an upside-down “V” above it, they say, signifies separation.

“As far as I know, no theory is definitive,” says Ramona Peters, director of historic preservation for the Massachusetts Wampanoag tribe. “There is one theory saying the Chinese left the artifact. They would use the language of the people they were hanging out with before, which accounts for the European letters on the stone.”

Another favorite theory, heard around the picnics and public lectures at the Dighton Rock Museum, posits that the stone is the last record of a doomed Portuguese expedition to the area which ended with a violent confrontation with the region’s Indigenous people. The carving, they say, was a historic record left by survivors of that doomed expedition.

“The symbols do not speak to us as much,” offers Peters, “and by ‘we’ I mean our tribe and other native people. We do have petroglyphs in our culture, but the symbols here are not familiar.” Figural representation in Wampanoag art, like the human forms depicted on the stone, were especially uncommon. “The people,” she says, “did not put themselves above other things.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook