How a Rare Book Appraiser Passes Judgment in 30 Seconds or Less

A discerning eye often means a disappointed collector.

On the main exhibition floor of the 58th Annual New York International Antiquarian Book Fair, sprawled across the 60,000-square-foot drill hall of New York City’s Park Avenue Armory last weekend, a buzzing grid of vendors peddled books and ephemera. The oldest item was an illuminated scroll dating to the 13th century, and the priciest—a first edition of Copernicus’s study of the heavens—held an astonishing $2 million price tag. All of the thousands of items for sale were guaranteed by the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, meaning that buyers could return their purchases for a full refund within 30 days if they spot unexpected defects or feel like they were misled.

In the hallway outside the entrance to the fair, there was a table full of appraisers, there to help put a value on any book brought to them. Dozens of bibliophiles queued up over the course of a two-hour appraisal blitz, bearing books and magazines with uncertain pasts and unknown values. These weren’t necessarily big-ticket antiquarians—rather, many were folks who hoped that they had chanced into a lucky find in grandma’s attic or a yard sale.

Sunday Steinkirchner, one of the experts on appraisal duty, knows how easy it is for people to get their hopes up. She has been selling rare books and manuscripts since 2003, and incorporated her business, B & B Rare Books, in 2005. People often call her for appraisals, either because they’re preparing to sell something or planning to insure it. She’s no stranger to working carefully but quickly, and either making someone’s afternoon or dampening their dreams of a quick payday.

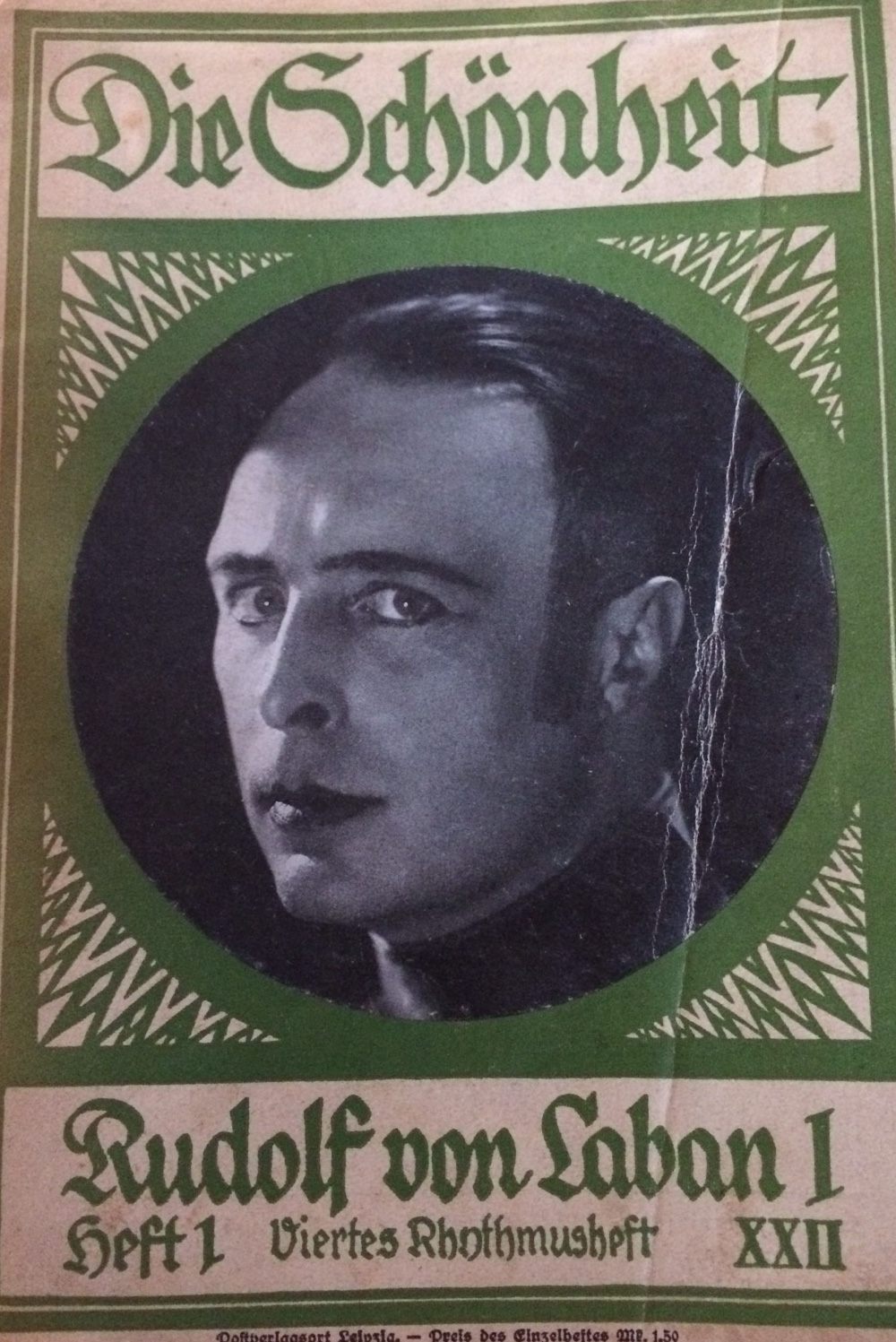

Alex Artaud was in line, holding items he hoped to have appraised. Some people lumped their books into totes and others packed them into rolling suitcases, but Artaud had his tucked inside a plastic sleeve. In particular he wanted to get a pair of trained eyes on his copy of a Weimar-era journal called Die Schönheit, a publication (the name translates to “The Beauty”) celebrating “free expression, and that includes not wearing any clothing, I guess,” he said. “But I wouldn’t call it a nudist journal.”

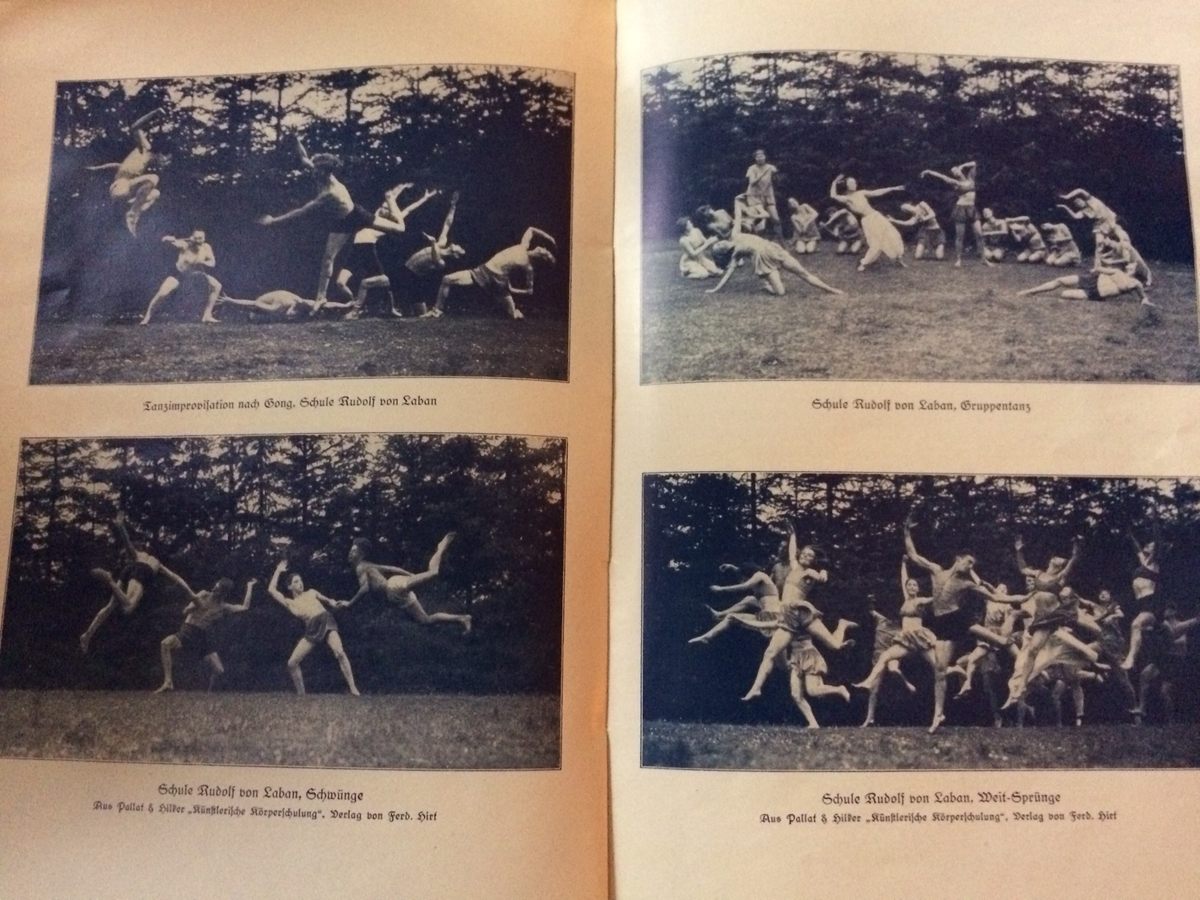

The 1926 issue is a tribute to Rudolf Laban, an important figure in the history of dance, and features exuberant spreads of his outdoor pageants, with dancers crouching or leaping across meadows like stags. Artaud nabbed it for a dollar at a flea market in Berkeley, California. “It was just there on the pavement, it wasn’t even protected—it wasn’t in a sleeve or anything,” he said. “I just think it was something in the house and they took it out because nobody knew what to do with it, and they figured, ‘Well, it looks old and interesting.’”

Artaud, who works as a theatrical technician, knew that Laban had worked on a robust system of dance notation, an important codification of a language often communicated through show-and-tell. He had a hunch that the periodical might be worth something when he couldn’t find any other copies online. “This one is somewhat distressed,” he said, gesturing to its distressed cover and binding, flaking like the layers of a croissant.

When his turn arrived, Artaud splayed the magazine out in front of Steinkirchner. “Right off the bat, I deal in mostly modern, first-edition English and American, so this is not my speciality,” she said. She nodded toward a colleague, who was busy with another appraisal. “I might ask Adam to help with this one, especially if it’s in German.”

The line was sizable, the time pressure pronounced, but Steinkirchner said later that it’s pretty standard to make swift work of an appraisal. “We’ve had years and years, some of us decades, of practice,” she said. “You can usually tell right away what type of book is valuable, and what is just an old, used book.” She estimated that it takes about 30 seconds to take stock of the cover, condition, publisher, date, binding, and signature, and then hazard an educated guess about the value. (Magazines, in general, tend to be worth much less than books, with a lot depending on condition.)

A book is more likely to be valuable if it retains its original binding and dust jacket—that flimsy cover can contribute as much as 90 percent of a book’s worth, Steinkirchner explained. “People sometimes say, ‘Oh, why do you get so excited about a little piece of paper,’” she said, but “collectors want to compile objects the way the publisher issued them.” At the event, she was especially excited about a copy of Thomas Wolfe’s 1929 novel, Look Homeward, Angel, with its original dust jacket. Given its condition, with minor chips and creases, but no repairs, she appraised the volume at $2,500.

Casual collectors don’t always know exactly what to look for, she pointed out. They might dismiss inscriptions that are made out to someone specific, for example, because they’re under the impression that a note—“To Jim, thanks for reading”—detracts from the value. Quite the opposite. Inscriptions are often preferable to a pristine leaf, especially if they’re made out to somebody significant, because that makes provenance easier to track. But even an anonymous recipient is better than none at all, because the additional lettering gives appraisers evidence for establishing authenticity and sniffing out forgeries. Signature, letters, and the way the ink is pressed—all factor into to the process. “The more the author wrote, the better,” Steinkirchner said.

As Artaud launched into his practiced description of his magazine, there was a lot of nodding. “Okay, great, mmmhmm, absolutely,” Steinkirchner said. “I tried finding another copy of this, and wasn’t able to,” he explained. “I found a reference to it in a library, but that was about it.”

As he spoke, Steinkirchner quickly searched databases on her phone. “There’s two places we can look, generally, to find value,” she said. “One is the current market—what’s available now—and then we also check the auction record of what books have historically sold for.” (Rarebookhub.com is accessible via subscription, and Abebooks.com is open to the public.) Being old, or even rare, isn’t enough to make something worth a lot or money, she added. Nothing has value without a market. In general, magazines were designed to be ephemeral and in wide circulation, and that puts a cap on their value, Steinkirchner warned. “The only reason I’m checking is because it could be something I just know nothing about, and all of a sudden, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s the one that is.’”

At events like this one, hope and reality don’t always find common ground. Rapid-fire appraisal events are needle-in-a-haystack scenarios, Steinkirchner said. “One out of every 10 or 15 things has any value whatsoever, and maybe throughout the entire day we’ll see a couple things that have value in the four or five figures,” she said. That means that appraisers are most often in the business of bearing bad news.

Steinkirchner appraised Artaud’s find at a little less than $150, because it hasn’t weathered the years as well as some other copies in Germany, which are finely bound or in perfect condition.

He didn’t seem disappointed. He hadn’t been hoping for anything specific—he just liked the magazine, and paid almost nothing for it. As an antidote to the things he scrolls by on his phone and the beautiful stage sets he strikes, physical objects with at least a little sense of permanence feel nourishing, he says. “When there’s something right there that has beauty,” he stretched out the words, “like handmade beauty, just one-of-a-kind things that have the care and love, that restores your faith in things.”

Even when the hopefuls handle a letdown gracefully, appraisers don’t take any pleasure conveying the news. “Most of the time, we’re saying, ‘I’m so sorry, this doesn’t really have any value—it might look old, it might look important, but, you know, really it’s this,” Steinkirchner said. She thinks accurate information is the best someone can ask for, even when it’s anticlimactic.

And then there are those rare occasions when something turns out to be as special as the owner hopes, or even rarer and more valuable. Rapid-fire appraisals are a good way to remind people that, while it’s not a good way to get rich, sifting through stuff can be rewarding for any number of reasons. “People sometimes bring stuff in and say, ‘I got rid of a house full of books, and this is what I have left,’” Steinkirchner said. “And I’m like, ‘Why did you get rid of them if you didn’t know what they were worth?’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook