How One Runestone Suddenly Reappeared After Being Lost for 300 Years

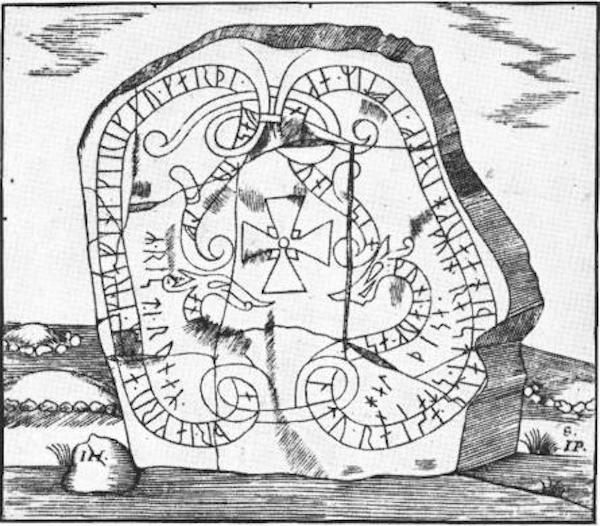

U 170 (Image: Johan Peringskiöld)

Torun Zachrisson always knew that a runestone once stood near the spot, just northeast of Stockholm, where she’d been taking archaeology students for almost a decade. Not far from the water, there was a Viking-era burial ground, and around 300 years ago, an antiquarian named Johan Peringskiöld had described a large stone standing in the area. He’d made a drawing, too, and Zachrisson, an associate professor at Stockholm University, had handed out copies.

“This stone has been lost,” she told the students she’d brought here on an April day in 2013. Supposedly, it had been cannibalized to build a jetty, out near the water. “But since you can see on the drawing that there are grave mounds nearby, it must have been placed somewhere here.”

She had told the same story to groups of students for years. But this time, as the day was getting on, and the sun starting to set, Zachrisson happened to look over her shoulder as the group headed back to their car. Suddenly, she saw the sun hit one particular rock, and she noticed something. There were signs on the stone.

She wasn’t sure what, exactly, she had seen, but she and the students turned around and went back to the burial ground. They had to clear away brush, and spring flowers, and fallen leaves. Once cleaned of debris, the lined rock started looking like part of a runestone.

Zachrisson had found a runestone before, but it was a fragment that had been smashed from a larger stone and lain at the burial ground. This was a much more substantial stone, and it was laid neatly on the soil. It might be the real thing.

In the car, on the way back to Stockholm, the group started comparing the photos they had taken with the 17th century drawing made by the antiquarian. And it matched. The bottom of the runestone in the drawing matched the markings on the rock they had discovered.

“I was so pleased,” says Zachrisson. “I realized that it had stood on the same spot, and it hadn’t been moved. It was on its original place in the landscape.”

U 170 in 2013 (Photo: Torun Zachrisson)

Although Viking-era runestones are found far and wide—the genuine article in Denmark, Norway, on the Faroe Islands, in Greenland, in Italy and Ukraine (and the fake in a few spots in America)—they’re most commonly found in Sweden.

Although they might seem like ageless, timeless monuments, runestones were a fad, tied to a particular place and time. They were most popular in the eastern provinces close to Stockholm that, more than 1,000 year ago, were some of the most densely populated parts of the region. And the majority of the more than 1,300 runestones found there were made in the tenth and eleventh centuries, where Sweden was just becoming Christian.

Erecting a runestone was the 11th century equivalent of buying an Apple Watch, a way for wealthy people to signal participation in the future, while still keeping hold of the past. And the stone Zachrisson found, Uppland Runic Inscription 170, told a particular story about how one family navigated that transition.

Scandinavian history was not well-documented with written words before the second millennium A.D., and runes are some of the only records of left of the Viking age and the years just after. There are pieces of wood and metal engraved with these lithe, angular characters, an alphabet that was replaced by Roman letters as Christianity spread through Europe. But most of the written records are on runestones, set up as memorials to the dead or as grave markers.

Two of the most famous runestones are in Jelling, Denmark, between two large mounds, at least one of which was a burial mound. The smaller of two stones was erected by King Gorm, in honor of his wife Thyra. The larger was the work of Gorm’s son, Harald Bluetooth, in the second half of the 10th century. It, too, commemorates Thyra, as well as Gorm. But the stone also celebrates Harald’s conquest of Denmark and Norway, and his conversion of those lands to Christianity.

It’s most common, in Denmark, Norway, and Southern Sweden, to find runestones erected around this same time. The custom only lasted for a few years in these areas. But in eastern Sweden, in Uppland, the trend of erecting runestones lasted for much longer, well into the 1100s.

Harald’s stone (Photo: Erik Christensen/Wikipedia)

Swedish antiquarians first grew interested in the runestones in the 17th century, around the time the Sweden’s territory and power grew and then quickly fell. Early in the century, the kingdom won wars against Denmark, Russia and Poland, and emerged from the Thirty Years War still a major force in Europe. But at the turn of the century, in 1700, Denmark, Russia and Poland retaliated, and in the next decade and half beat back Swedish expansionism, leaving the kingdom less rich and less powerful.

During this period, Swedish intellectuals started exploring Scandinavia’s more distant past, in search of an origin story that would match their new might, a glorious past that they could be worthy of. One leading scholar, Olof Rudback, was obsessed with tying Scandinavian history to the ancient texts of continental Europe: he developed a theory, for instance, that Atlantis was located in Scandinavia.

Johan Peringskiöld, who first recorded Zachrisson’s U 170 runestone, studied at Uppsala University, where just a few decades later Carl Linnaeus would do his famous botanical work. In 1680, Peringskiöld began work at the new college of antiquities, and as part of the project of documenting Sweden’s history, he traveled around the country, drawing and describing runestones and other evidence of the past.

“The antiquaries in the 17th century did a magnificent job,” says Zachrisson. “I’m very much indebted to them and grateful for what they did. They did this when the roads were bad, and it was so much more difficult to go around the country. But many stones have been lost or destroyed, and we still have their drawings. Without them, maybe we would have half or two-thirds of the knowledge of these runestones that we do.”

When Zachrisson and her students arrived back in Stockholm, she rushed back to her office, and the first thing she did was find the runologist.

“He was so excited,” she says, “He was in a bus going home, and he jumped off the bus.”

The runestone Zachrisson had found was special. For the most part, the inscriptions on runestones follow a simple pattern: They note that one person raised the memorial in honor of another, give the relationship between the two and sometimes details on the family. It’s more common, especially on older runestones, for both people to be men, connected by family and inheritance. It’s largely in looking at the stones as group that scholars have been able to better understand the lives these people lived.

But U 170 is a little bit different. Its inscription, translated, reads:

Gunni and Ása had this stone and the vault raised in memory of Agni, their son. He died in Eikra. He is buried in the churchyard. Fastulfr carved the runes. Gunni raised this stone slab.

Not all of this translation is certain. The son’s name for instance, might also be read as Ond or Eyndr, and the name of the place where he died is not certain.

What’s most interesting about the stone, though, is its in-betweenness, both in the text on the stone and its location. It’s on the edge of an old graveyard, where people are buried in the traditional way, that overlooks an old harbor and route to the sea—the main orientation of the older society. But it also reflects a connection to Christianity.

“It alludes to a traditional type of burial, and yet the son is buried at the churchyard, where there was probably then a wooden church,” Zachrisson says. The word for “vault,” too, is a new word, describing a newer type of runic monument, erected in a churchyard. Earlier runestones would not necessarily have been placed where a person’s body would, and church burial was a new option. But after churches began appearing in the area, as burials moved from traditional graveyards to churchyards, runic monuments started moving, too, and became closer to gravestones, marking actual graves, than memorials.

“Maybe having the stone on the edge of the burial ground was a way to have a foot in both camps,” the old and the new, says Shane McLeod, a research fellow at the University of Sterling, who studies Viking-era history. With Christianity becoming more popular, “Your burial customs change. You can’t be buried in a mound, or cremated. You can’t be buried with your sword, your boat, your slave. But you don’t want to dismiss everything you’ve believed in the past. Your ancestors were very important. It could have been a way not to forget your family.”

Soon, though, Christian traditions would take over more fully, and Scandinavian society would change. Runestones were often moved from their original locations and incorporated into church buildings, likely as a way of honoring their power. The runic monuments in churchyards, too, reflect shifting powers: women start being mentioned more often, and children, too.

“You can see social inequality and social differences via the inscriptions,” says Zachrisson, and how those forces change over time. “It’s quite extraordinary source material.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook