How Photographs Printed on Paper Changed 19th-Century America

Shareable images have always had an impact.

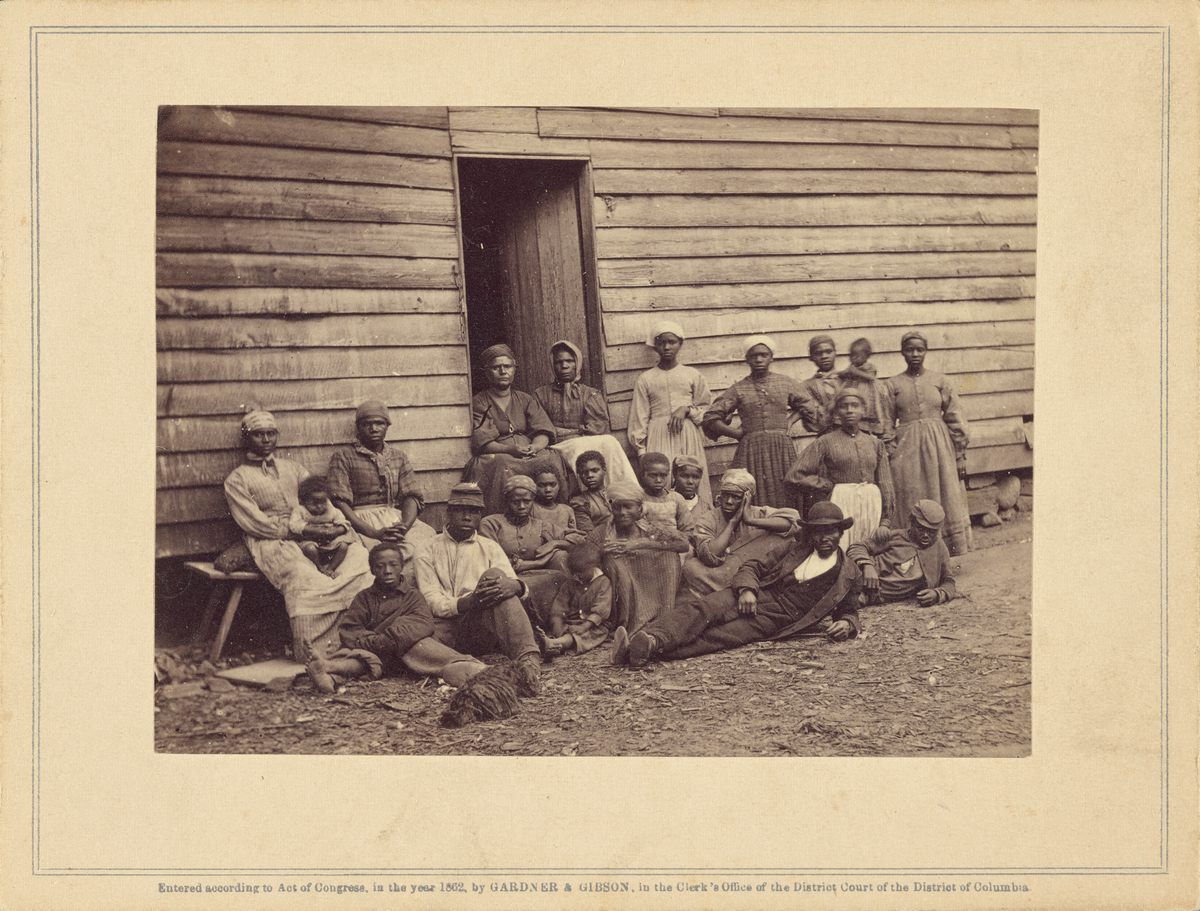

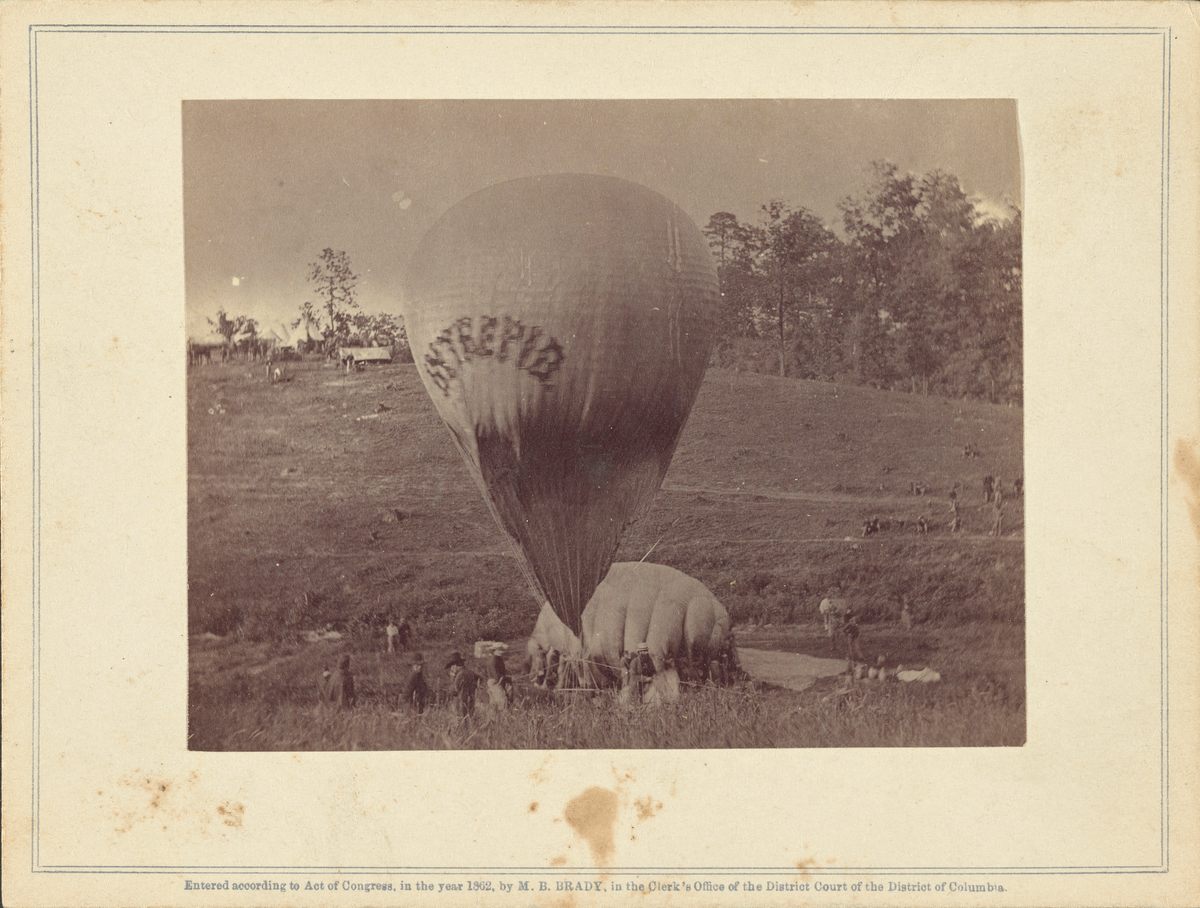

Throughout human history, technological advances have changed how we relate to one another. This is especially true of photography. In the 19th century, the sudden ability to print images on paper—a material that’s both shareable and disposable—eventually gained widespread and long-lasting use. And as a new exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles demonstrates, this photographic process ultimately also became an influential social force.

“We sometimes tend to think about photographs as documents or illustrations of history,” says Mazie Harris, assistant curator of photographs at the Getty Museum, which opened Paper Promises: Early American Photography this week. “It was important for me to think about the ways in which photographs are agents in history, in really bringing about change or really giving people a sense of the world.”

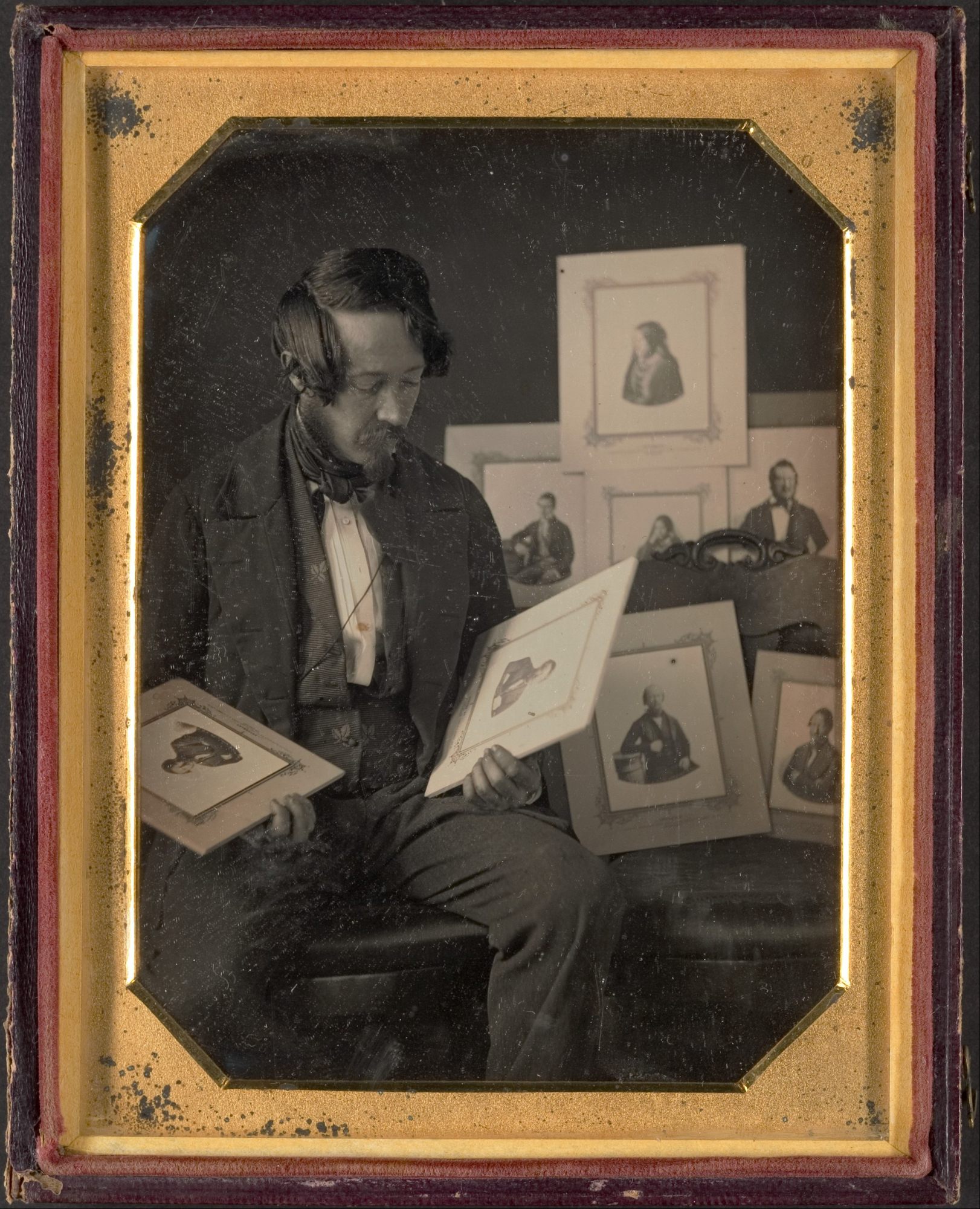

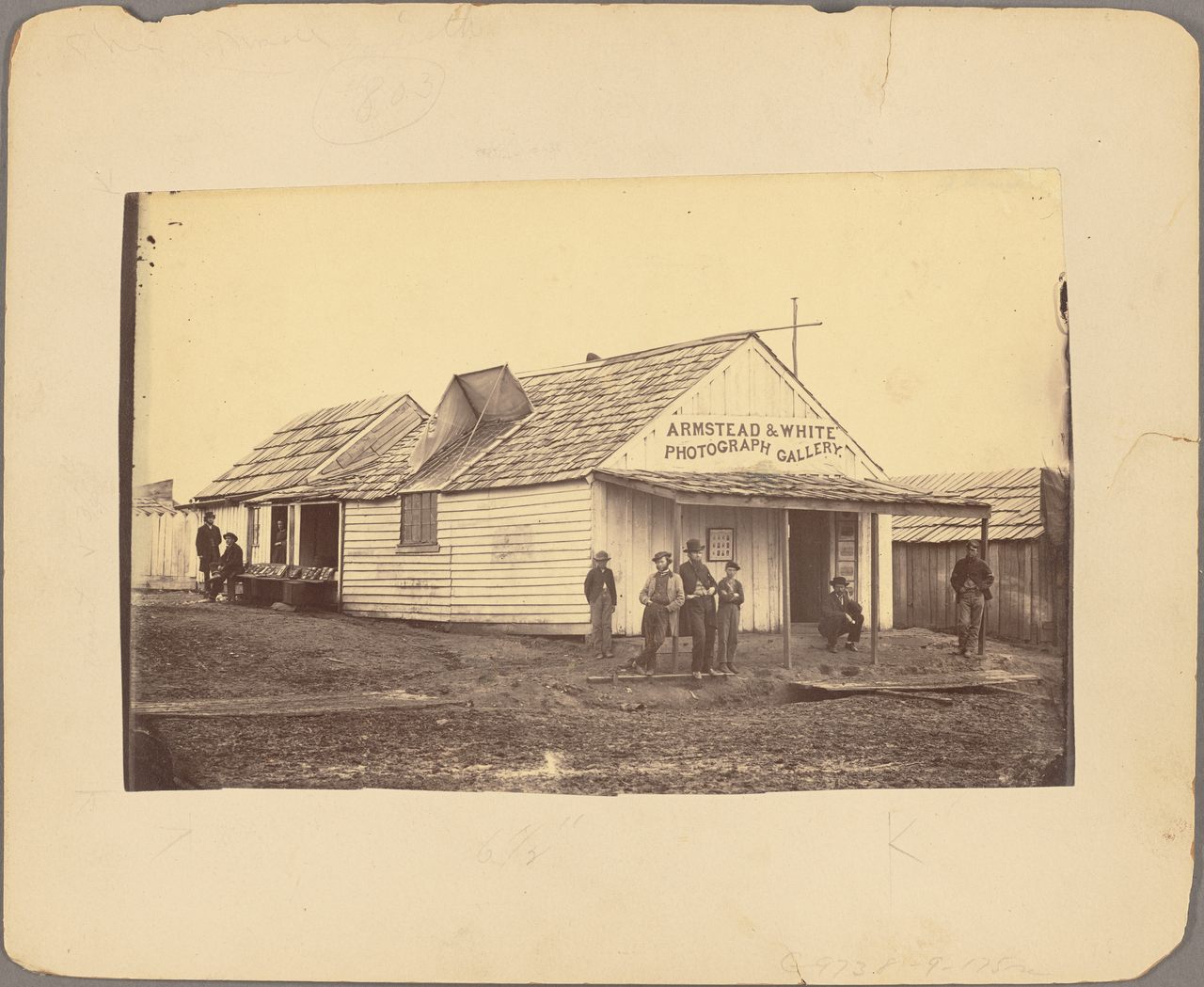

In mid-19th century Europe, photographers quickly realized the benefits of using paper to create prints from negatives. But in the United States, there was some reluctance. Part of the problem was the fear that it would contribute to the widespread use of counterfeit money (‘paper promises’ was a 19th-century term for fake currency). Photographs were usually displayed on metal or plate glass surfaces, which don’t exactly lend themselves to portability. But some American photographers saw the potential of this new technique. Printing on paper meant that photographs could be created and shared for all the same reasons we might use post an image on Instagram or Facebook today: self-promotion, as a memento, to document travel, to advertise something, or to promote political causes.

“With a lot of photographs in this exhibition, you can see that they were folded and sent through the mail, or they were quite small and could be easily shared,” says Harris. “You really get that sense of it becoming more and more available as a social tool because it can be made in multiples.”

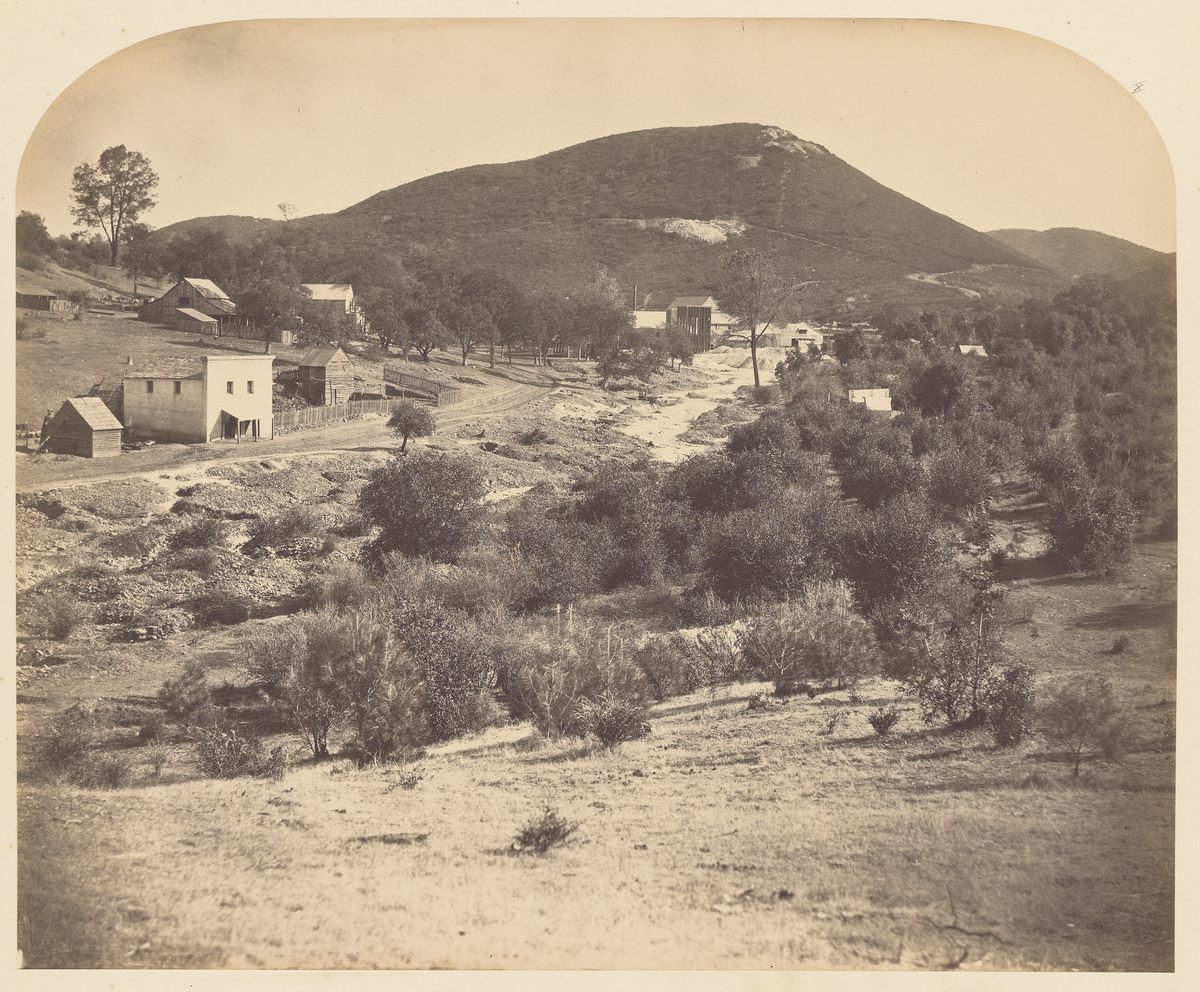

This is particularly true, notes Harris, of the photographs in the exhibition that deal with the expansion into the American West. One photograph shows a group sitting on the front of a steam locomotive, forging ahead to, presumably, their future. Harris learned that this photograph was originally a promotional image made by the railroad company. “It really does give that sense of positive progress, moving forward, the dynamism of the railroad. Photography in that same way was really about creating new networks of sharing information,” she says.

It’s also important to look at the people in such images. “If you take the time to look really closely at the people’s faces, you see a sense of determination,” says Harris, a quality she thinks the photographer themselves shared. But, as she notes, “there’s a real lack of diversity in that image. Just as it offers a sense of progress it also excludes certain people from that wall of progress.”

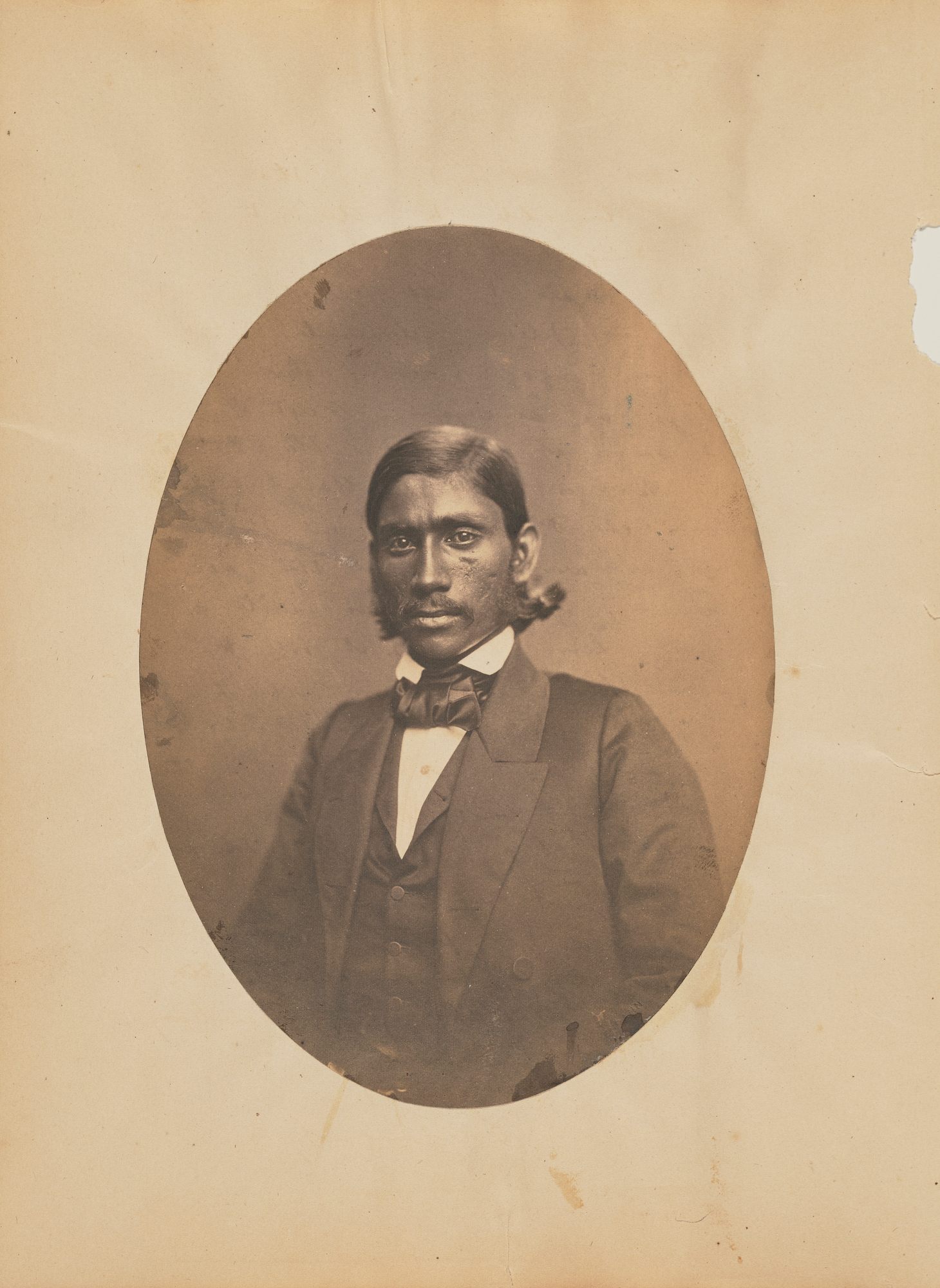

Easily reproducible photographs had an impact on territorial issues of the day. According to Harris, there was a real public interest in images of the Native American delegates who visited Washington, D.C., in 1857-1858. The photographer Julian Vannerson took a series of studio portraits which include, Harris notes, “these inscriptions of the names of the sitters that are this really botchy transliteration of the pronunciations of their names.” Another photographer kept outfits at his studio for the delegates to wear, which more closely matched white Americans’ perceptions of Native Americans.

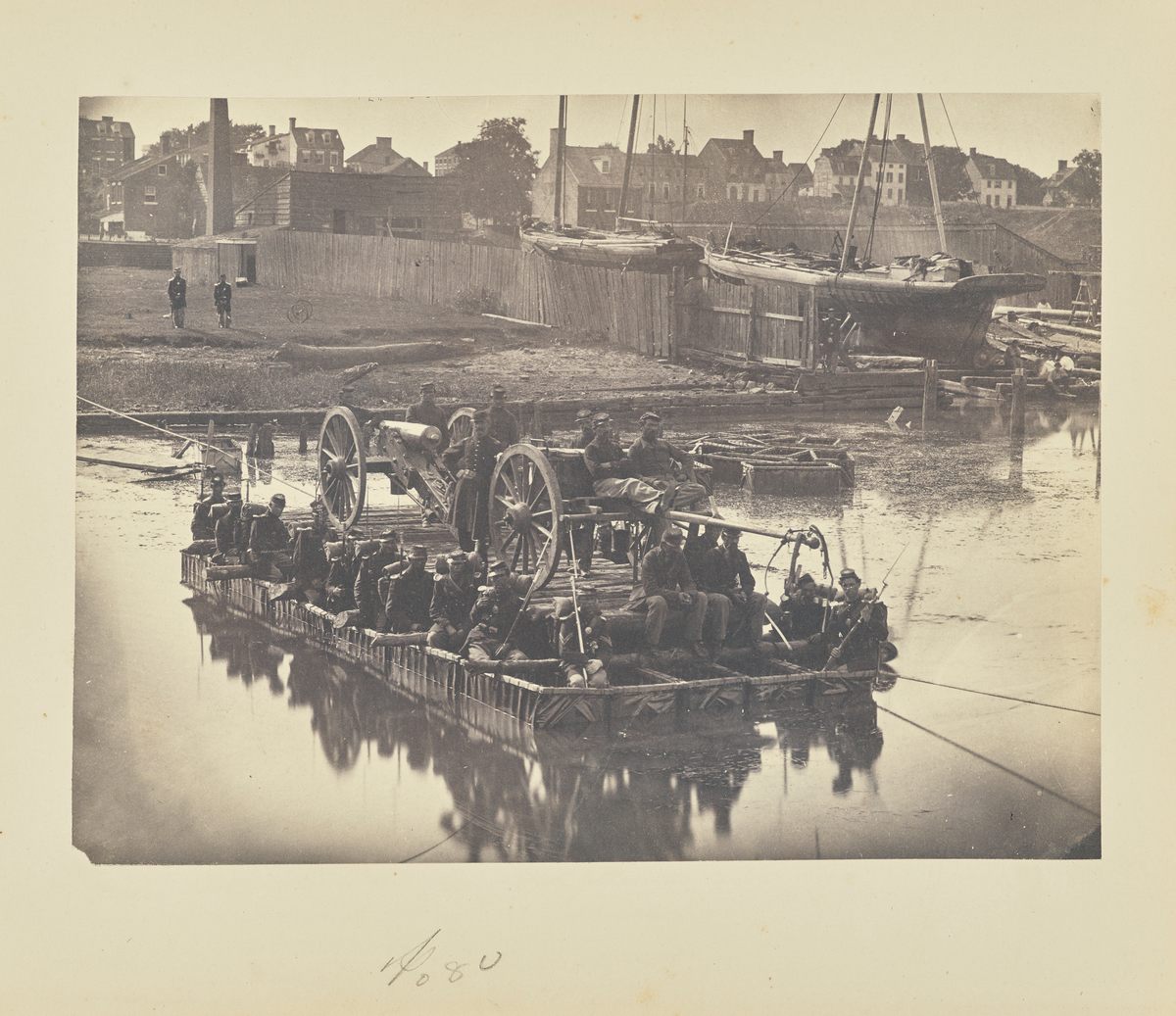

The increased ability to share photographs also coincided with the Civil War. The accompanying exhibition text includes a quote from the 1862 American Journal of Photography on the popularity of portraiture among soldiers:

“America swarms with members of the mighty tribes of cameristas… The young Volunteer rushes off at once to the studio when he puts on his uniform, and the soldier of a year’s campaign sends home his likeness that the absent ones may see what changes have been produced in him by war’s alarms.”

“There is an explosion of interest [in photographic printing], both for the soldiers to document for loved ones, but also for the cause,” says Harris. After the war, photographers also shared images of the devastation and, in some instances, casualties, as a way to promote pacifism.“This was incredibly shocking for people to see these first-hand images of death in that way, and I think it had a profound impact,” says Harris.

Today, of course, we can take and share a photograph in a matter of seconds, distributing it across the digital world for anyone to see. “One thing that is important to me about this show is that photography is about objects,” says Harris. “We tend to think of them as something we experience with our eyes, but this 19th-century material was hand-held material—the same way that we cradle our cell-phones, and flip through them with our hands.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from the exhibition, which runs through to May 27, 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook