How The Hidden Track Faded From Recorded Music

(Photo: AngeloDeVal/shutterstock.com)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

The music industry’s transition to digital everything has made for great gains in convenience for listeners.

But we have also lost things along the way—think of record sleeves, media towers, and Tower Records. And, perhaps most irreplaceably, the hidden track.

The secret bonus songs and obscure skits were among the few things about an album that couldn’t easily be converted to MP3 or Spotify. Why is that? Simple: When everything’s a file and Siri can dig it up for you if you ask nicely enough, there’s simply nowhere to hide anymore. And it’s a shame, because the hidden tracks were the only interesting part of some albums.

Let’s look back on how the hidden track became such an important art form.

While musical Easter eggs really shined during the CD era, there were plenty of examples that predated the introduction of lasers to music-playback devices.

The world first cottoned to the idea thanks to the Beatles, whose sound engineers used the form to override the wishes of the musicians themselves. An act of quiet defiance by one of those engineers gave Abbey Road listeners a little surprise at the end—and the world its first “hidden track.”

Little, literally: “Her Majesty,” the song that closes out the second side of the record, was just 23 seconds long. A simple acoustic ditty by Paul McCartney, the song was basically a loose end from the medley that defines the back half of that album. It was a nice enough song, but there was nowhere to put it in the midst of all the other songs on the record, so McCartney ordered engineer John Kurlander to remove it from the album.

He did, but later added it to the end of the album after a few seconds of silence.

“The Beatles always picked up on accidental things. It came as a nice little surprise there at the end, and he didn’t mind,” Kurlander later recalled.

A stack of CDs. (Photo: Tekke/flickr)

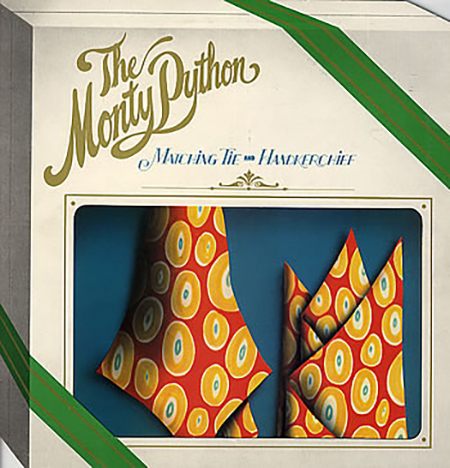

Another recording engineer with ties to the Beatles is responsible for at least two other types of vinyl-era Easter eggs. George Peckham, who worked at Abbey Road on many of the band’s records, helped the comedy troupe Monty Python figure out a clever vinyl-pressing trick they had batted around for a while but failed to figure out on their own: The three-sided record.

Peckham pulled off the trick on the band’s The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief, which came out in 1973. The record featured a concurrent groove, which made it so that it would play different music based on where you placed the needle.

The goal was confusion—something assisted by the fact that both sides of the record are labeled “Side 2.” The comics basically wanted listeners to trip upon the third side by accident.

“We had these visions of stoned fans, of which there were a lot in the early ’70s, having the shock of their lives when brand new material was playing on a record they had had for months,” Python’s Michael Palin recalled. “Some people thought there was an alternative version because they would hear talk of these mysterious sketches that they had never heard on their record. It drove people mad. This was precisely why we did it, of course.”

The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief, where both sides of the record were labelled ‘Side 2’. (Photo: WikiCommons)

Peckham eventually left Abbey Road Studios, but he wasn’t done with the music industry. Eventually, young bands would go to him, interested in his vinyl-pressing services. He was happy to help, but he wanted to put a stamp of his approval on the records he made.

To do that, he created the “run-off groove,” in which hard-to-see messages are placed onto the dead area of the wax.

Peckham generally called his records “A Porky Prime Cut,” though he was known for offering up a variety of other phrases of this nature. His trick eventually got into the hands of the artists, some of whom—like Joy Division and The Smiths—put a lot of thought into the end result.

It was a fun trick, but only a small sign of what was to come.

The compact disc was such a forward-thinking format when it first came out in 1982 that it needed its own bible. That bible was called the Red Book.

The book, formulated by Philips and Sony, explains the detailed technical specifications of the format, including the maximum length of a CD (74 minutes), the maximum number of tracks there can be (99), the minimum length of a single track (4 seconds), and the standard sampling rate (44.1 kHz).

(If you would like to read a copy of the Red Book, be prepared to pay: as it describes the innards of a proprietary material, it’ll cost you a solid $295.)

The Red Book also hid within its specifications a number of opportunities to do really interesting things with albums that you couldn’t do during the vinyl era. For one thing, you could mess with the track listing by adding a few seconds of silence between tracks; for another, you could actually put music before the official start of the album, in an area called the pregap. It’s a spot so hidden—only accessible by rewinding the CD as far back as possible—that most computers to this day still can’t access these hidden tracks.

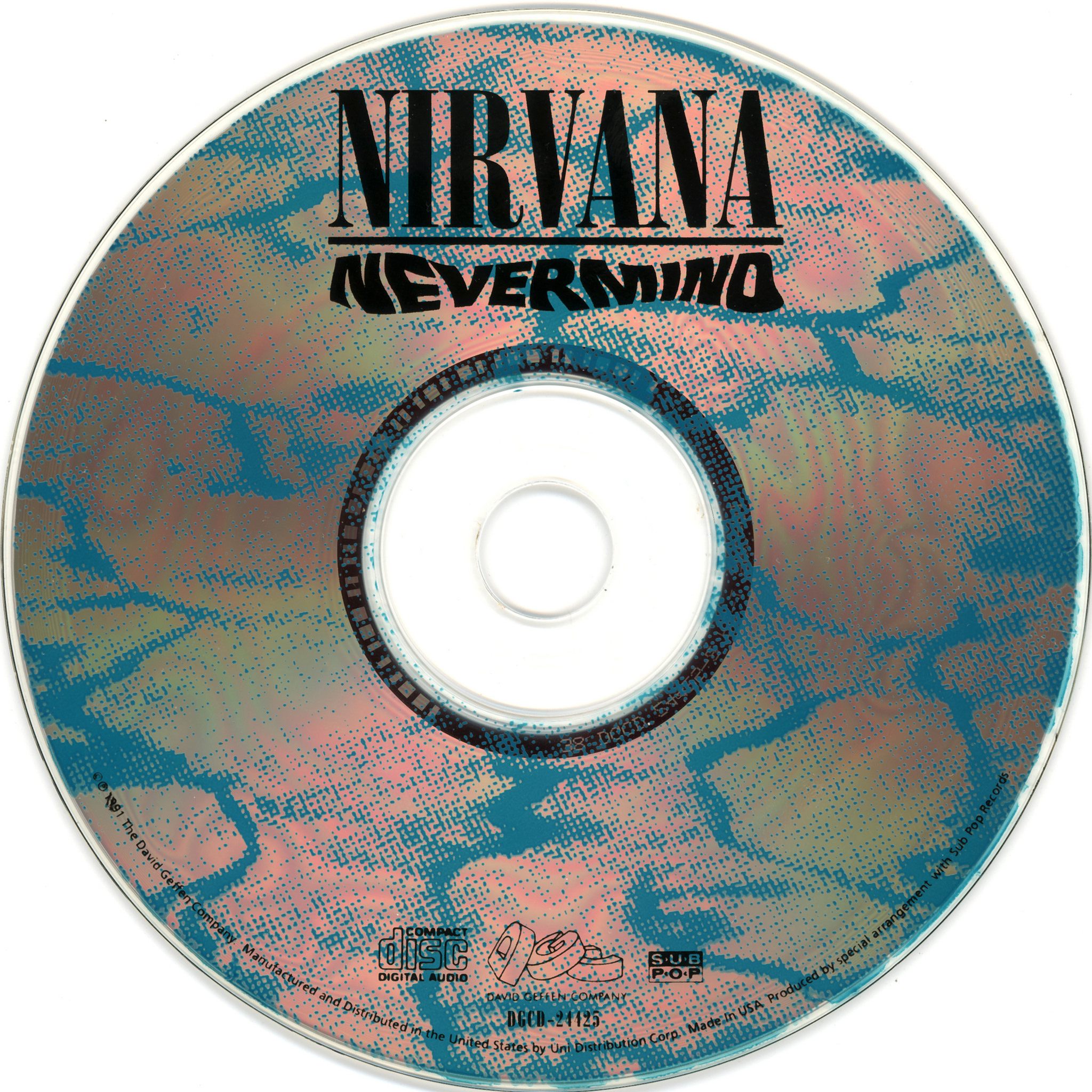

For the most part, hidden tracks at the end of the album tend to hide full songs (famously “Endless, Nameless” at the end of Nirvana’s Nevermind), while hidden tracks in the pregap area tend to hide introductory music in most cases. (One notable exception to that rule is the Northern Ireland band Ash, whose album 1977 included the band’s pre-album single, “Jack Names the Planets,” in the pregap.)

Nirvana’s Nevermind, which held the hidden track Endless, Nameless. (Photo: Wishbook/flickr)

Even now, new albums are taking advantage of these tricks—even though most buyers are most likely never hearing them in this form. A good example of this is the Arcade Fire’s most recent album, Reflektor. The first disc of the double album includes a 10-minute pregap track of reversed instrumental music culled from other parts of the album.

Unfortunately, the pregap was a better trick when we were using five-disc players. Computers, for the most part, don’t recognize pregaps, and modern DVD and Blu-Ray players don’t register them either, as one Arcade Fire fan learned when his Blu-Ray treated the pregap as part of the first track of the album, leading to confusion among fans on Reddit and elsewhere.

While CDs made hidden tracks a regular event, most of them functioned as a goofy one-off or a musical accident given room to breathe on a record. But there are a few examples of records where the hidden tracks became famous on their own merit.

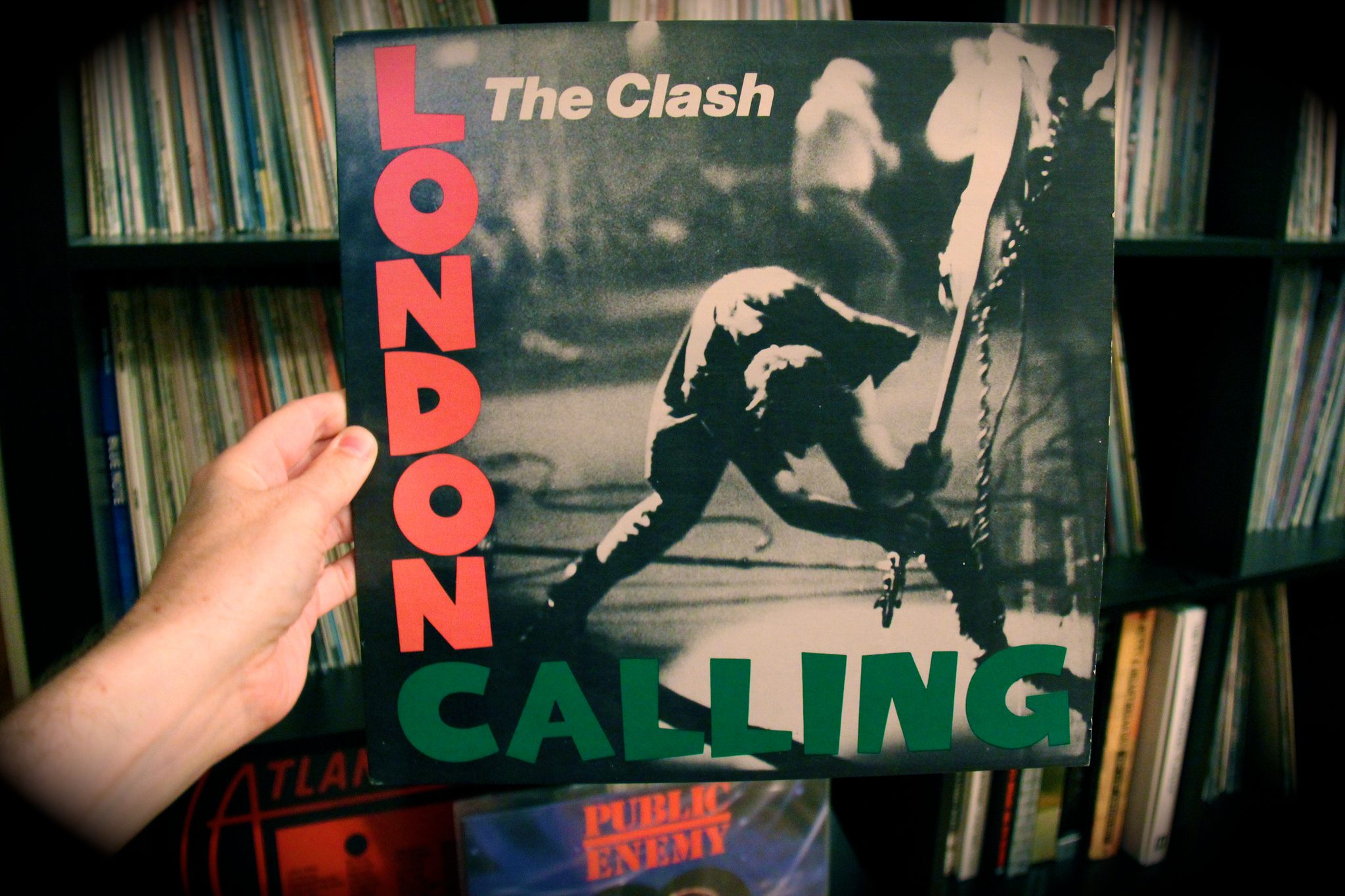

Perhaps the most noteworthy example is The Clash’s “Train in Vain.” The song was added to the band’s landmark London Calling after the sleeves had already been printed, but quickly became popular in the U.S. , where it was one of the band’s two Top 40 hits.

Arcade Fire on stage in Chicago. (Photo: Mary/flickr)

The ’90s alt-rock band Cracker had a similar rationale for their song “Euro-Trash Girl.” The tune, one of three hidden tracks at the tail end of the band’s 1993 album Kerosene Hat, essentially got added to the album after it was already completed, due to positive reaction from fans. Their decision proved wise after the song became a hit. The album took advantage of one of the CD era’s numerous tricks—an excessive number of blank tracks—to ensure the track was listed at track number 69. (Real mature, guys.)

Covers also tended to be popular targets for hidden tracks—and at times such covers transcended their hidden status. Lauryn Hill’s rendition of “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You,” featured on her immensely popular 1998 album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, was such a critical success that it received a Grammy nomination—one of 10 that she received for the album,

On the other hand, sometimes it’s a cover that helps make a song more prominent than ever. The ever-profane “B*****s Ain’t S**t,” an unlisted track on Dr. Dre’s landmark 1992 album The Chronic, found a second life on the pop charts in 2005 after Ben Folds made a version that introduced it to a whole new audience.

Finally, there can be artistic reasons for burying a track. That last situation happened to Mark Oliver Everett, better known as Eels. After he wrote a radio-friendly song called “Mr. E’s Beautiful Blues,” his label pressured him to put it on his record Daisies of the Galaxy. He did so because the label essentially said they wouldn’t release the record unless the song was included. It broke the flow of the album in his view, so he made it a hidden track.

The label made it the single and forced him to put the song in a Tom Green movie. Not so hidden.

London Calling with the hidden track Train in Vain. (Photo: @HayeurJF/flickr)

By the point that Eels was fighting his record label for proper placement of one of his most popular songs around 2000, the hidden track was facing some serious overexposure—a fact that is often lost in fond reflections on the practice..

“It’s time for musicians and labels to rethink why they hide what they hide,” wrote Scott Sutherland in a 1999 New York Times essay, “If most artists have a hard enough time filling even half the space on a 74-minute CD with compelling material, why bother hiding something equally uncompelling? And if a song is good enough to be the best thing on the disk, why hide it at all?”

As annoying as they were for the listener, they could often be just as annoying for the label. A 2014 Wondering Sound piece on hidden tracks noted how They Might Be Giants really angered Elektra Records by including a pregap track on their 1996 album Factory Showroom. The reason for this is that such tracks require a more detailed production process, meaning that the label has to do more work to ensure that the discs are up to snuff during the pressing.

Perhaps the only people who are truly happy to see the demise of hidden tracks are those who had to make them. process.These days, we just call these extra pieces of art what they are: bonus tracks. No hiding necessary. It’s not like Spotify will let us hide them anyway.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook