How To Escape From Handcuffs

(Photo: underworld/shutterstock.com)

Let’s say you get handcuffed. Let’s say that, once restrained, you decide that the whole being handcuffed thing is not so appealing, but you don’t have easy access to the key that will bring you freedom.

We won’t ask any questions about how you got there. But if you find yourself in this scenario, and would like to be released from your shackles, there are a few ways to go about it. We approached Schuyler Towne, competitive lock picker and Security Anthropologist at the Ronin Institute, for his advice.

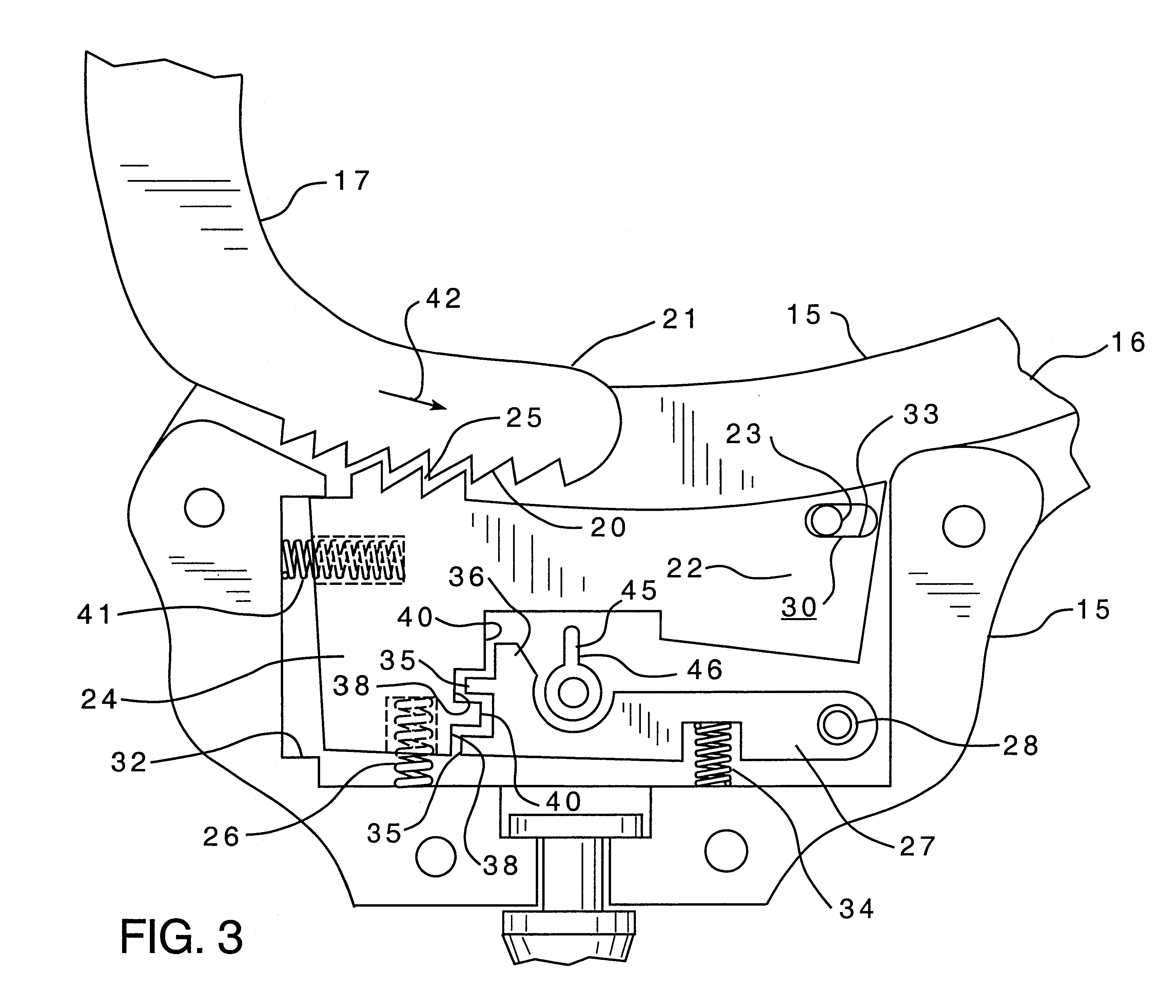

Before we get into the details of breaking free, it’s essential to establish the terminology we’ll be dealing with. The part of a handcuff that swings is called the shackle, and is equipped with a ratchet, or row of teeth, that interlocks with a row of teeth on the “pawl,” a part inside the thick bit of the cuff where the shackle is inserted. The part known as the “key way” is the lock itself—the hole where you insert the key to unlock the cuff.

The image below, from a 2002 patent for a handcuff locking mechanism, shows the shackle (17) and its ratchet (20). The pawl is the big part labeled 22, and teeth of the pawl are labeled 25.

(Image: Public domain)

Option One: Picking the Lock

The Captain Obvious approach to escaping handcuffs is to slip the end of a bent bobby pin or paper clip into the lock, twist and jiggle, and pray that your hands are released. If the person who handcuffed you wasn’t too careful about restraining your movement as much as possible, this may be a good option. As for the right tools, “all of the classics from film and TV do actually work,” says Towne, citing the scene in Terminator 2: Judgment Day when a faux-catatonic Sarah Connor spits out a paper clip, then uses it to free herself from her locked restraints and hunt down the T-1000 cyborg assassin.

According to Towne, replicating the shape of a handcuff key is pretty simple. All you need to do is bend a little hook at the end of a bobby pin or paper clip, so it can slip under the lip of the lock when you twist it. Obviously, this is a task best tackled well in advance of being handcuffed. Preparation is key.

Option Two: Shimming

The lock-picking approach relies on you being able to twist your hands around a bit. When your wrist mobility is compromised, the task will be trickier. That’s where the art of shimming, using the bypass method, comes in.

“If you’re handcuffed appropriately, you should have your hands behind your back, palms apart, with the key way facing the sky,” says Towne. “In that position, it is incredibly difficult to access the key way. However, the shackle will still be within range of your fingers, so you can still attempt that bypassing method.”

Instead of poking around in the lock, shimming works by inserting a thin strip of metal beneath the ratchet of the shackle. But there’s a catch: you then have to tighten the cuff.

“You can bypass it by simply slipping a small piece of metal along the shackle as you close it a bit tighter on yourself,” says Towne. “Even one position tighter on yourself and the piece of metal will interrupt the pawl and the [ratchet on the shackle] from being able to interact with each other.”

Here’s a video demo of how that works, courtesy of a survival skills group called Black Scout Survival:

The need to tighten the cuff makes this method a dicey one, says Towne: “If you don’t get it right the first time maybe you have a second shot, but you probably don’t have a third. At some point you get super tight onto your wrist and, you know—you’re screwed.”

A bobby pin with the plastic end bobble pulled off can be used if the opening between the shackle and pawl is big enough—no need to create a hook at the end, it ought to remain straight—but purpose-built shims work best. And Towne says you can easily carry them around every day—concealed, of course.

“I used to keep handcuff shims in the hems of my shirt, because they’re thin enough and flexible enough that they can go through the washing machine without screwing them up,” he says. “You can also get through a pat-down without anybody discovering them.”

(Photo: Klaus With K/Creative Commons)

Extra Obstacle: Double Locks

Shimming, while simple, only works on handcuffs that have single locks engaged. Some handcuffs are double-locked, which adds another layer of difficulty to the escape process. In these scenarios, a peg is pushed into the pawl, preventing the shackle from budging. Unless you remove the peg first, the bypassing and picking methods won’t work.

“There are two types of double locks,” says Towne. “The one used by the Peerless corporation is friction-based, so it’s just a peg that has been pushed into the lock, preventing the [shackle] from going anywhere. So, potentially—and it hurts like heck, but I have done it and other people have demonstrated it—if you take your wrists and bash them against something solid, you can potentially unseat that double lock and then carry out the bypassing attempt.”

“The other method that Smith & Wesson and some others use is a sprung double lock, where when the double lock is set, there’s spring pressure down on it and just bashing it against something won’t unseat it. It’s very difficult to unseat without the proper key.”

Moral: if you’ve just been handcuffed, try to ask—casually—who manufactured the cuffs in question. The answer will determine whether your action plan should involve bashing your wrists against a wall or simply crying in defeat. Good luck, and may the spirit of Harry Houdini guide you.

Houdini in handcuffs, looking pretty chill about it. (Photo: Bettmann/Corbis/Public domain)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook