Mummifying a Beetle Is a Lot Easier Than Mummifying a Cat

Not all animal mummies were created equal.

The rabbit had looked better. Two days dead, it was swollen and rank, and riddled with holes to let gases escape. Five days later, it swarmed with beetles. Its head had exploded, and the pelt pulled away from its bones. To approximate the result of baking under the desert sun, it had been sitting on a bed of natron, a type of salt, and perched on a laboratory rooftop.

It was 1999, and along with her students at the American University in Cairo, Egyptologist Salima Ikram had been reconstructing ancient techniques for animal mummification. Working on the 1.8-pound rabbit had been more than a little grisly, but that didn’t mean it was going wrong. The team had no reason to believe that, when all was said and done, they would end up with anything other than a mummified rabbit, much like the old objects Ikram had studied. But due to “health and sanitary considerations,” they later wrote, they called the experiment off. The team interred the corpse.

Ikram is an expert in animal mummification and a proponent of experimental archaeology, from which she’s gleaned first-hand knowledge about what it takes to preserve a non-human body. Her team carried some of their other experiments to the end. A few other rabbits were eviscerated, exsanguinated, and wrapped in linen strips sealed with melted resin. The researchers also tried their skills on two ducks and a couple of fish. One of these, a catfish with individually swaddled whiskers, had vanished, after having become “extremely attractive and tempting (still) to a local raptor who flew away with it,” Ikram notes in the book, Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt.

Though scores of scholars have studied mummified human remains, Ikram writes, “less attention has been paid to their animal counterparts.” This is despite the fact that “as many, if not more, variations in mummification technology were practiced on animals compared to humans,” Ikram continues. These techniques included evisceration and desiccation, cleansing the intestines and then packing the body cavity with natron, and injecting oils into the anus to dissolve the viscera from the inside. At least one canine mummy was built from disarticulated bones, and live birds were occasionally plunged into vats of melted resin, pitch, and bitumen, Ikram writes. The submersion killed and preserved them in one stroke.

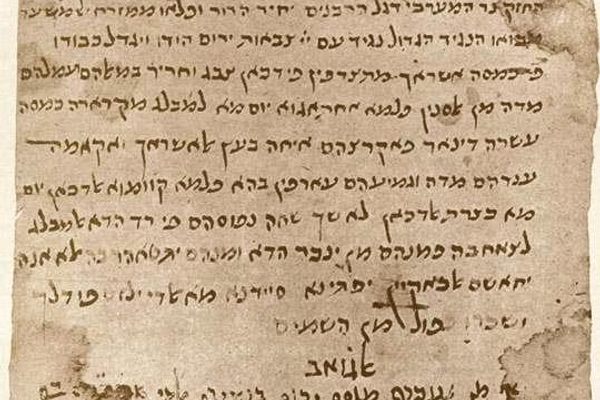

Ancient Egyptians mummified monkeys, gazelles, crocodiles, bulls, shrews, snakes, and more, and Ikram has studied many of these. So when a slew of mummified scarab beetles were recently found during archaeological work across several Fifth Dynasty tombs in the King Userkaf complex of the Saqqara necropolis, she wasn’t particularly surprised. The linen-wrapped scarabs, which were placed inside a limestone sarcophagus, are “something really unique,” Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, told reporters from Reuters and other wire services. “It is something really a bit rare.”

#Discovery Unique #Discovery in #Saqqara #Giza #Egypt #mummies of #scarabs #AncientEgypt pic.twitter.com/FkCA9HxY5P

— Ministry of Antiquities-Arab Republic of Egypt (@AntiquitiesOf) November 10, 2018

Mummified beetles may be rare, but they were probably pretty easy to pull off, Ikram says. While she hasn’t conducted experimental work on scarab beetles, she expects that they’d be good and dry after three, four, or five days in the sun. “Not long, basically,” she says. “If it’s a small animal that’s not very fat—like a mouse—a week or 10 days will do it.” A hefty bull would require a hundred days, at least.

The larger the animal, the bigger the logistical puzzles of mummification. It boils down to the quantity of fat, and whether or not viscera would need to be removed. In the case of the scarab beetles, “there’s absolutely no need to mess with those poor creatures in that way,” Ikram says. Crocodiles and snakes, on the other hand, are wildcards. Less fleshy and fatty than mammals, and much scalier, it is unclear whether they would have always been eviscerated—as human and larger animals mummies often were—or just left out to dry.

Ikram and other archaeologists have found that there were a number of reasons to mummify animals and arrange them in tombs. Sometimes, mummification was a way of exalting treasured or beloved animals. In most other instances, mummified creatures served as offerings. The animals were raised for this specific purpose and their mummies were sold near temples, sparking a substantial industry—as well as a black market. (Occasionally, sham mummies were packed with little more than feathers, sticks, and clumps of earth.) Like raptors and shrews, Ikram notes, scarab beetles were symbols of Ra, the sun god, and were probably given as offerings to him.

Mummified scarabs didn’t take much effort, but Ikram says the discovery offers valuable insight into funerary traditions. “It’s hard to get into the heads of ancient Egyptians,” she says, and since this tomb appears to have been essentially untouched since 2,500 BC, everything inside it helps researchers puzzle out where things were placed and why. The inventory “helps us piece together what the ancient Egyptians’ intentions were,” Ikram says—one tiny mummy at a time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook