How to Find the Best Stuff in the Night Sky From Absolutely Anywhere

A beginner’s guide to admiring stars, planets, and satellites—no mountaintop or fancy gear required.

As part of our Atlas Obscura Goes to Summer Camp special package, we’re revisiting stories that have captured the summer camp vibe or explored some of its more unique subcultures. Enjoy this curated classic!

The first time I saw Saturn’s rings, I was up on the High Line, the pedestrian greenway built atop an old train track just west of 10th Avenue in New York City. It was far, far from where I grew up in rural Ontario, Canada, where the night is dark as obsidian and the sky, on a clear night, looks sequined. I took it for granted that the sky was huge and reliably wonderful. As a kid, I loved keeping watch for shooting stars, and we always seemed to spot them. I wasn’t hungry to see more—to look closer at things such as Saturn’s icy bands or lunar craters—until it became much harder to do so.

Manhattan is not a great spot for stargazing. There’s too much light, and the city is too low and too humid, with too many tall buildings eating up the sky. Generally speaking, the highest, driest conditions lead to the crispest, most dazzling views, which is one reason that professional astronomers trek to arrays at the South Pole or remote desert mountains, and some deeply invested amateurs work with telescopes they can access remotely. But while those conditions are crucial for science, for seeing distant stellar nurseries or studying black holes, they’re definitely not prerequisites for seeing something cool.

Sarah Barker, an astrophysicist and science communicator, stargazes in New York, too. She cuts through an urban park to get home every night, and says that “more often than not, you can see a few things—a bright planet, Orion—really clearly.” Atlas Obscura asked Barker, author of the book 50 Things to See in the Sky, and other experts, to teach us how to stargaze from pretty much anywhere. “Even in the biggest, brightest city in the world,” Barker says, “there’s always something to see.”

Locate yourself in space-time

To determine what will be visible when you look up, you need to know “where and when you are,” Barker says. That is, you’ve got to determine your latitude and consider the time of year. Several constellations are only visible from one hemisphere or the other, and various stars and planets are easiest to observe at certain times of year. Some observatories, such as the famed Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, issue weekly reports about what’s happening in the sky so you know what to look for. Apps such as Star Chart can help you get your bearings by using your phone’s GPS to sketch out the constellations you should be able to see—helping you to literally connect the dots.

You’ll also want to figure out what’s going on with the lunar cycle, because the moon can either improve or obscure your view, depending on what you want to see. If you’re looking for the Milky Way, for instance, or faint, distant objects, your best bet is to wait for a moonless night. If you’re planning to look for something on the moon itself, though, you probably want to do so when it’s full.

Get a handle on the weather

It helps to check the forecast and steer clear of downpours or gray days—but a crystal-clear night is not critically necessary. A couple of clouds aren’t a deal-breaker, Barker says, and they sometimes pass quickly, leaving clear skies behind them. “High, wispy clouds—not a problem,” she says. “Big, thick, fat rain clouds—problem.” There’s no reason to call off your search unless the cloud cover is significant and looks like it won’t budge.

Don’t be obsessed with gear

No need to run out and drop thousands on a fancy telescope—Barker has never owned one, and doesn’t plan to. “You don’t need one to see stuff and fall in love with the night sky,” she says. You can make out plenty of constellations with nothing but your eyeballs. The first third of Barker’s book is dedicated solely to stuff you can spot with the naked eye. And a simple, easily portable pair of binoculars can bring things into sharper focus.

If you want even more detail, drop by a public stargazing night at a local observatory, or meet up with an astronomy club, which will probably have telescopes trained on the sky and people stationed on the ground to field questions. To find one near you, check out this directory from Sky and Telescope.

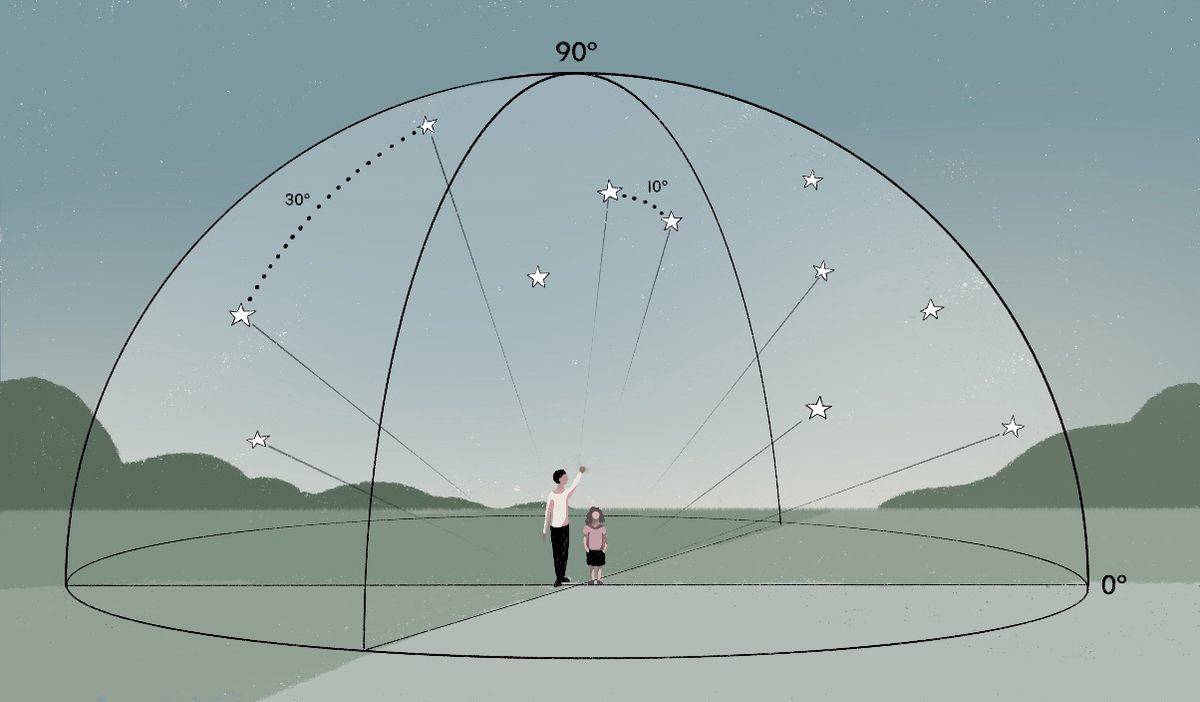

Brush up on your measurements

If you’re looking for a specific star or planet, you might find their distances described in degrees, with zero degrees referring to the horizon, and 90 for the sky directly above you. To zip from one location in the sky to another, you can use your body as a navigational tool, Barker writes. Extend your arm away from you and make a fist—the width of your clenched hand is about 10 degrees. Splay your thumb and pinky finger, and that shape is about 25 degrees. “Using some combination of these can help you find your way when guides say things like, ‘Look 15 degrees southwest to see this object,’” Barker writes.

Focus your search

If there are buildings in the way, you don’t have much choice of where to look. Otherwise, you might want to narrow your view. The full night sky is vast and overwhelming—but there’s no need to try to take it all in. Barker recommends exploring the area around Orion, because it’s dense with things to spot. She calls it “Orion and neighbors.”

That subdivision of the sky has “lots of cool stuff,” she adds, and it rewards close looking. With the naked eye, you can see the constellation’s sword and other iconic shapes. (In the northern hemisphere, look southwest to find the three stars that form Orion’s belt. In the southern hemisphere, you should be able to see him in the northwest part of the summertime sky.) Gaze up at Orion’s right shoulder, and you’ll see Betelgeuse, a future supernova so bright and massive—hundreds of millions of miles across—that its reddish glow is easily visible here, hundreds of light-years away. With binoculars, you can appreciate the nebula known as Messier 42, or the Orion Nebula, a stellar nursery visible as “a faintly fuzzy patch” below Orion’s sword, Barker writes. The nebula is easiest to see when Orion is highest in the sky. In the northern hemisphere, that means your best chance at spotting it is likely to be around midnight on December or January nights.

Get to know an old favorite

You’ve definitely seen the moon—but there’s a lot going on there. Try to find the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo 11 touched down in July 1969. Next time the moon is full, look for the Tycho Crater. (From the northern hemisphere, it will appear like a bright, pitted spot toward the bottom of the disc, even with the naked eye, though binoculars or a telescope could help.) Then, look for the dark splotches nearby that resemble a lobster claw. The portion closest to the crater is the Sea of Tranquility. You’re not going to see the bootprints in the regolith, but trust us, they’re there.

Don’t forget about the human-made stuff

The International Space Station (ISS) zooms through low-Earth orbit, around 250 miles up. At roughly 17,500 miles per hour, it orbits the planet every 90 minutes—and you can often spot it from the ground.

The ISS and other satellites “are only visible during dawn and dusk, when the sky is dark but the sun’s light is still arcing around the planet, illuminating shiny objects passing overhead,” says Lisa Ruth Rand, a postdoctoral fellow at the Consortium for History of Science, Technology, and Medicine, who studies objects humans have launched into space. “The contrast is key.”

To figure out exactly when the ISS will be passing overhead, consult NASA’s Spot the Station, which has a live tracking map and 6,700 suggested sighting locations around the world, updated several times a week by Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. You can sign up for text or email alerts that will ping you when the ISS passes by at 40 degrees or higher, giving you the best chance of spotting it. Barker also recommends the ISS Spotter app, which shows you the angle and duration of visibility you can expect, and even allows you to set an alarm so you’ll remember to run outside to catch it zooming by. Rand uses SkyView, a sky-mapping app that includes satellites.

You’ll be able to distinguish the space station from a plane because it won’t have any blinking dots on the wings. “It’s just a point of light, whipping and more arched, and bright,” Barker says. Also, “it’s booking it—it’s moving fast.” The ISS is “easy to see with the naked eye, even in urban areas with light pollution,” Rand says. And when you do spot it, remember, there are fellow humans up there, staring down at Earth. “I often find that people will stop and ask what I’m looking at,” Rand adds, “and when I tell them, they are astounded that that moving star is a space station with people on it.”

It’s easy to discount the night sky, or assume that its wonders can’t be revealed without a powerful telescope and perfectly cooperative conditions. But really, there are scores of wonders to be spotted, whether you’re in Manhattan or on Mauna Kea. You just have to look.

This story originally ran in 2019; it has been updated for 2024.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook