How Amateur Astronomers Used a Remote Observatory to Peer at a Nearby Galaxy

Hey there, neighbor!

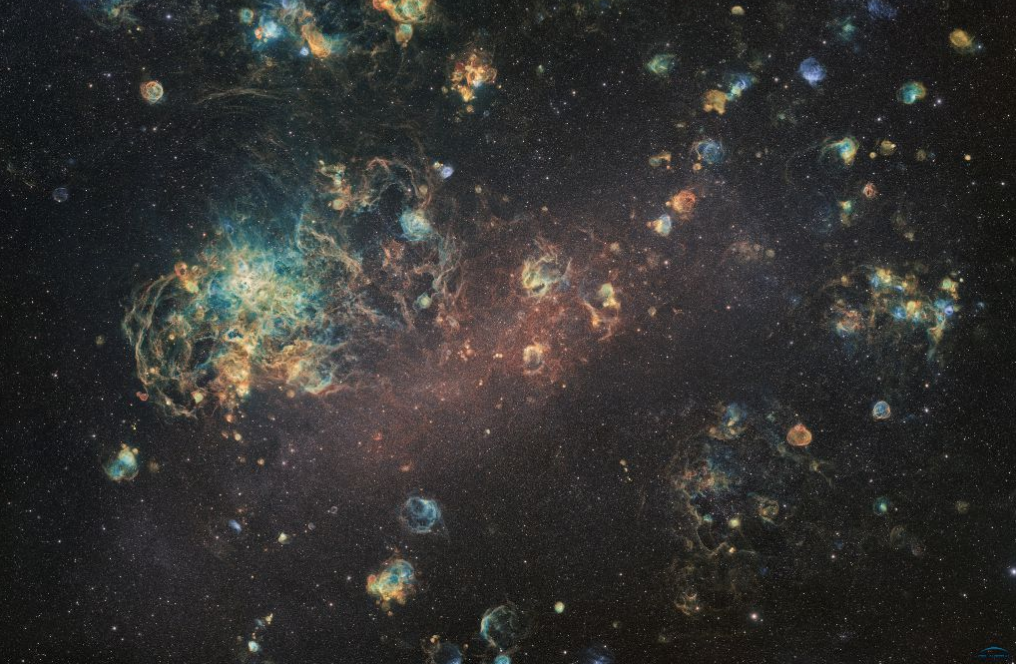

Laurent Bourgon has never visited the Large Magellanic Cloud. No human has—this gas-filled galaxy, ablaze with newly born stars, is some 160,000 light years from Earth, according to NASA. Still, it’s a familiar sight in the darkness—relatively close to us, as far as space distances go, and is often visible from Earth as a smudge in the southern hemisphere sky. Now, Bourgon has glimpsed it from one of the best viewing spots on our planet, and helped to capture an image that can make it feel just a little bit closer.

In 2018, when Bourgon visited Observatorio El Sauce, in Chile’s Atacama Desert, “I thought I was in paradise,” he says. Bourgon, an amateur astronomer who lives in France, was enchanted by the view. Stargazers prize this region’s low humidity and lack of light pollution; the sky is said to be clear roughly 320 nights a year. Standing outside in the darkness, Bourgon says, “You can see the shadow of your body with the Milky Way light.”

That made it an ideal place for Bourgon and his collaborators to site their telescope. The five-person team, called Ciel Austral, uses Bourgon’s software, called MaxPilote, to remotely control their TEC160 refractor telescope and a Moravian G4-16000 astrophotography camera down in Chile while they were far from the setup.

The sky conditions are an obvious improvement over the ones in France, Bourgon says, where cold, cloudy nights dampened a bit of the appeal (and likely payoff) of stargazing. And the software is able to adjust the settings to respond to a particular target, moonlight, and more. The software “does it all for us,” Bourgon says. Back in France, “we can go to sleep.”

This image was assembled from 1,060 hours of observation that spanned 10 months in 2018 and 2019. The raw data took up 620 GB, and 16 panels were stitched together to make this field of view. This version includes color filters that detect specific wavelengths of light to make faint structures more vivid. In all, it took a month of finessing to arrive at the final image. Suffice to say: If you go outside tonight and crane your neck to the sky, you won’t see something like this, looking like levitating bubbles or oil-streaked water. But the image is transfixing, transportive, and beautifully otherworldly.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook