In Syria, War and Modernity Are No Match for the World’s Oldest Soap

The artisans of Aleppo keep plying their ancient trade, one bar at a time.

When I was a kid, my father would sometimes come home with a suitcase full of earthy-smelling olive-green soap. It was knobbly and waxy and marked with curious Arabic inscriptions that I couldn’t yet read or understand. I wanted to use the same soap my friends were using: a familiar, machine-pressed bar of pink Imperial Leather, whose fragrance mimicked the artificial perfumes in my cosmetics. But my father insisted I use only the Aleppo soap. It was a cleaner, healthier choice, he said. It was a better soap.

Many years later, after my father died, I was sorting through his belongings. I came upon the small leather suitcase he brought with him to the U.K. the first time he left Syria. Inside was a scrunched paper bag filled with Aleppo soap, now aged and turned the color of deepest gold. I decided to investigate: Why did he care so much about this soap?

What I learned was a historical legacy too good to keep to myself. And I may have learned it just in time, as violence is threatening to wipe Syria’s cultural heritage clean off the earth.

The Syrian Civil War has been raging for eight years now. In that time it has decimated the ancient tradition of soap-making in Aleppo. Nearly the entire industry’s workforce was forced to flee when the fighting started—some to other cities, some to new countries altogether.

Today, though the war rages on in parts of Syria, government forces have mostly regained control of Aleppo, and the city is slowly coming back to life—and going back to work. That includes some of Aleppo’s traditional soap-makers, who are renovating their workshops and reviving production. With help from government organizations and charitable funds, the soap is again becoming a popular and profitable Syrian export.

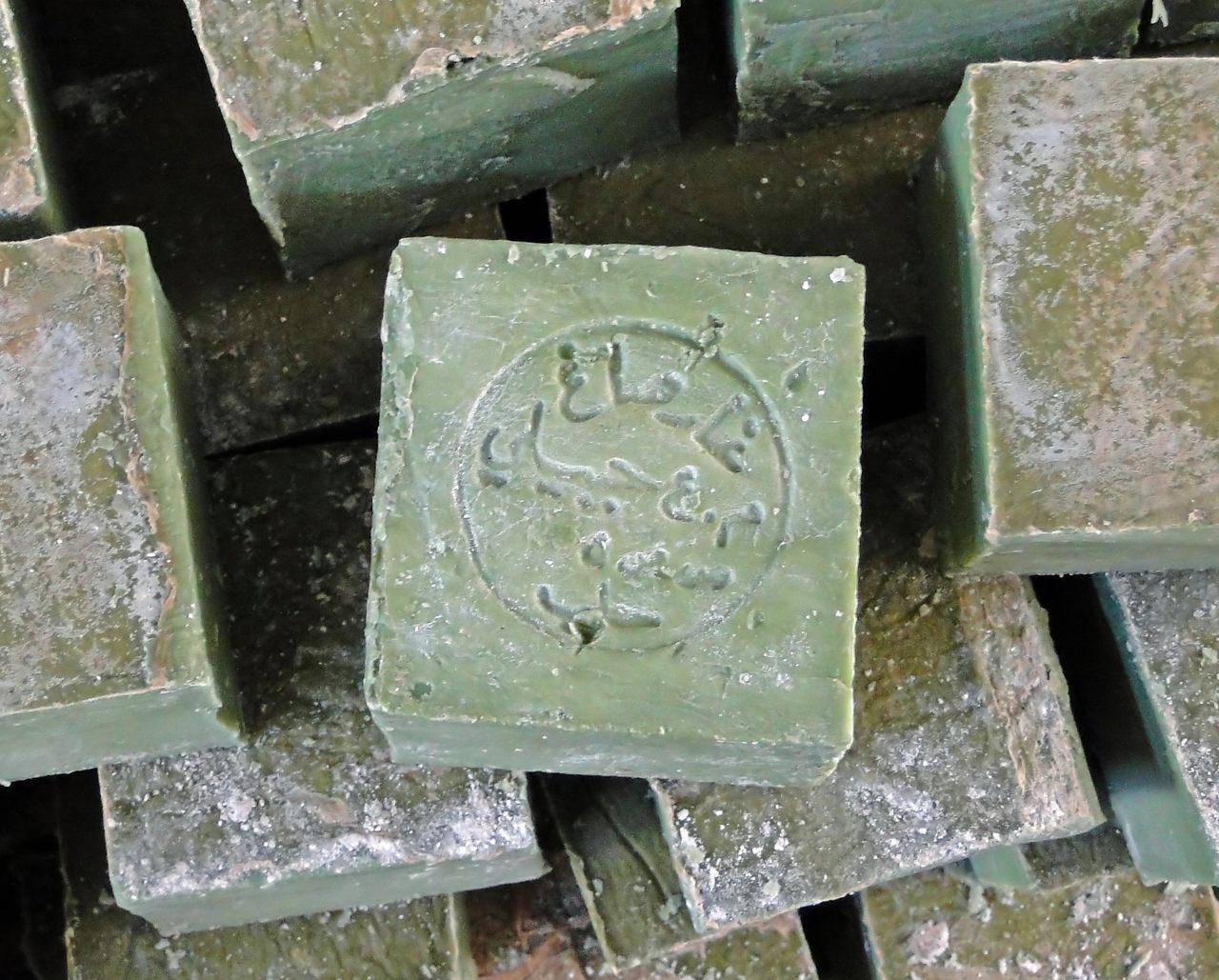

Aleppo soap, known as ghar in Arabic, or Savon d’Alep, is revered by aficionados around the world. Many historians consider it to be the world’s first modern soap bar—solid, rectangular, and used for bathing and personal hygiene. Made by hand, it contains just three ingredients: olive oil, laurel oil, and a tincture of lye. It has no animal fats or derivatives, no harmful chemicals or artificial colors. The result? An intensely moisturizing and delicate balsam widely used by those with sensitive skin, including small babies and those who suffer from eczema, psoriasis, and acne.

For thousands of years the leaves and berries of the laurel tree—Laurus nobilis—have been a symbol of wealth and prosperity in the Mediterranean. The tree’s fronds crowned the heads of ancient Greece’s powerful elite, figures in classical sculptural works, Roman emperors, and victorious gladiators. But it’s the elixir of the tree’s berries that contain the magic ingredient of Aleppo soap—an essential oil with medicinal properties shown to contain anti-fungals, anti-microbials, anti-inflammatories, and more.

While its genesis is lost in the mists of time, Aleppo soap may have evolved from the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia (modern-day Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Kuwait). Sumerian textile traders are known to have used a saponaceous liquid solution, created from a concoction of animal fat and wood ash.

Several of Mesopotamia’s great cities remain today, including two in Syria. One is Damascus, the 11,000-year-old Syrian capital widely believed to be the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. The other is Aleppo, thought to have been continuously inhabited for 8,000 years.

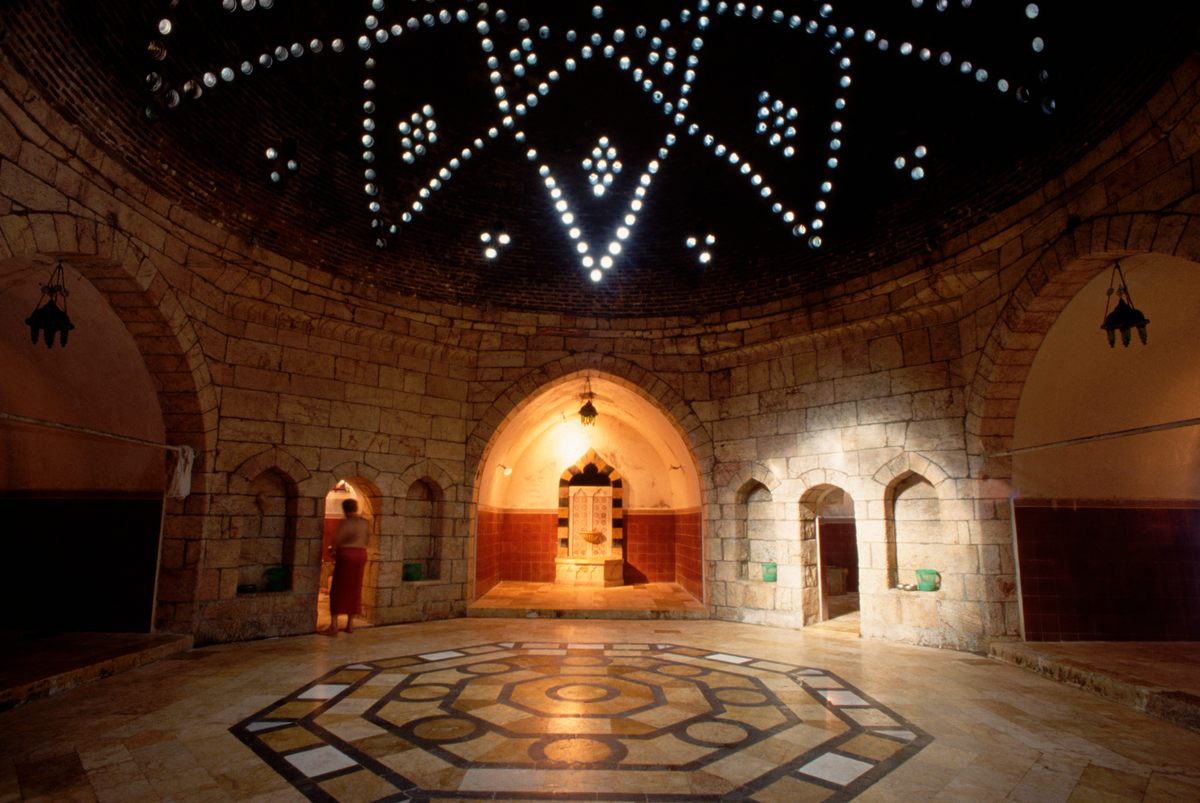

The soap’s lineage becomes a little clearer between the years 100 and 200, when Syria was a Roman province. It was at this point that large heated bathhouses, or thermae, first appeared in the area and kick-started the hammam bathing tradition (known today as Turkish baths). In these social settings, men compared their soaps and tonics—a practice that led to the crafting of fine soaps.

As centuries passed under the rule of various empires and dynasties—Byzantine, Umayyad, and Ottoman, to name a few—the public bathing tradition became more refined, and more opulent. The soaps used by bathers became more sophisticated too, laying the groundwork for the Aleppo soap we know today.

When the Crusaders returned to Europe loaded with treasures from the East, news of the fine Syrian soap they’d found reached the masses. Subsequently, soap production increased in Aleppo, and soon became integral to the city’s economy. Exporting it was simple, thanks to Aleppo’s key position along the historic Silk Road trading route.

Soon European soapmakers were replicating the product as best they could. The celebrated Savon de’Marseille and Castile soap are believed by some to be two such iterations. But the Aleppo soap’s centuries-old production process, and the select precious ingredients unique to the Syrian region, cannot be fully replicated.

The harvesting process begins in the fall in Syria’s mountainous north, when the inky-black berries of the tree are ripe. From October to December they’re picked by women whose livelihoods are tied to the harvest. The collected berries are then sold to oil merchants in Aleppo or Damascus, or processed closer to home by the communities that harvest them.

Once the essential oil has been distilled, it’s mixed with olive oil, which comprises the vast majority of the soap’s content. The greater the ratio of laurel oil to olive oil, the more expensive the finished product. A single bar today will usually cost $4 to $10, depending on its laurel oil content.

Next comes the saponification process—a chemical reaction between an acid and a base to form a salt. In this case, the oil mixture is heated with small amounts of lye until a thick, dark green solution is produced. The solution is poured onto the stone floors of large drying chambers beneath each soap factory, forming a thick carpet of green gloop the size of a tennis court.

Once the gloop cools and hardens, it’s cut into blocks by one of two methods. The first involves wooden shoes with blade attachments, which resemble ice skates. One worker will strap on a pair of the shoes and offer up his arms to fellow workers, who propel their colleague along the soap slab. An alternative method uses a rake-like device instead of shoes. But the same principles apply. After one worker mounts the device, his colleagues pull him along with ropes.

Whichever method is used, the green sheet is neatly sliced into rectangular hunks roughly five inches long by four inches wide. Each bar of soap is then stamped with the maker’s mark, as well as the Arabic name for Aleppo: Halab (حلب)—an important distinguishing feature and stamp of authenticity.

The final stage in the process is drying and curing. Hundreds of bars are arranged together into attractive vertical shapes—usually a pyramid or a dome—which allows each bar to receive maximum exposure to the air. These soap towers are then left out for months in the factory cellar, where temperatures are relatively constant—neither too hot nor too cold. The soap cures throughout the winter and early spring before it’s sold to the public.

Yazan Sabouni’s factory was among the first to reopen after the government regained control in Aleppo. Together with his two brothers, Abdullah and Zaher, the 23-year-old Yazan runs a business that’s been in his family for over a century. Even their last name, “Sabouni,” means “soapmaker” in Arabic.

The war has badly roiled their ancient tradition. “[During the fighting] almost all of the soap-makers left Aleppo,” says Sabouni. “Some traveled to other cities, and some left Syria altogether … [after their factories and shops were] demolished. We thank God that we just lost our money and buildings, and not our lives.”

Reparations and renovations in the city are now under way, but it will take time for the industry to fully recover. Not only were buildings damaged and destroyed; costly equipment was stolen from the factories by looters.

The result has been a literal decimation of the ancient Aleppo soap industry. “Before the war there were more than 200 large [soapmaking] labs and small workshops,” says Talal Anis, another prominent soapmaker. “Now there are no more than 20.”

Soapmakers aren’t the only ones whose livelihoods have been imperiled by the war. Many of Aleppo’s famous soap-selling districts were within the walls of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Much of the Ancient City—including the Al-Madina Souq, a covered market that’s home to numerous khans and bazaars—suffered severe damage in the 2012 Battle of Aleppo. These merchants are still recovering as well.

But for many of Aleppo’s soapmakers, preservation hinges on a speedy recovery. Like the Sabounis, the Anis family business has been passed down through generations. Talal Anis began working with soap when he was 16, under the guidance of his father. He doesn’t want to be the last generation to practice the family trade.

“I want to make sure that the Aleppo soap industry is here after me,” he says. “For my family, for all residents of Aleppo, and for the world.”

Yazan Sabouni agrees. “Our people have taken care of themselves and their bodies for thousands of years,” he says. “Aleppo soap is as important as French perfume, Swiss watches, or Italian pasta.”

But the real recovery process begins with the full return of the workforce—the displaced men and women who, together, form the lifeblood of the industry. Anis is optimistic. “With support and time,” he says, “the industry will recover.”

However much things may yet change in Aleppo, one thing that can never be washed away is the humble bar of soap. Its recipe and story will continue to be passed down through the hands of Aleppians, whether in the souks of the Old City or the suitcases of migrants.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook